London Symphony Orchestra

Strauss & Wagner

Welcome and Thank You for Watching

Whilst we were unable to come together with audiences at our Barbican home, we were pleased to continue recording concerts behind closed doors for streamed broadcast, making music available for everyone to enjoy digitally.

It is a pleasure to invite you to watch and listen today online as LSO Music Director Sir Simon Rattle conducts music by Richard Strauss and Wagner. We extend thanks to our broadcast partner Marquee TV for streaming this concert. I hope you enjoy the performance.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Rattle conducts Strauss at his wittiest and Wagner at his most uninhibited. This is Tristan and Isolde as you’ve never heard it before.

Thursday 27 May 2021

Strauss & Wagner

Richard Strauss Le bourgeois gentilhomme – Suite

Richard Wagner orch Leopold Stokowski Symphonic Synthesis of Tristan and Isolde

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

This performance is broadcast on Marquee TV. Available to watch for free for seven days from 27 May, then on demand with a subscription.

Recorded at LSO St Luke's on Thursday 6 May 2021 in COVID-19 secure conditions.

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra, assist our recovery from the pandemic and allow us to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO’s return to work is supported by DnaNudge.

Generously supported by the Weston Culture Fund.

Share Your Thoughts

We always want you to have a great experience, however you watch the LSO. Please do take a few moments at the end to let us know what you thought of the streamed concert and digital programme. Just click 'Share Your Thoughts' in the navigation menu.

Richard Strauss

Le bourgeois gentilhomme – Suite

✒️ 1911–17 | ⏰ 35 minutes

1 Overture

2 Minuet

3 The Fencing Master

4 Entrance and Dance of the Tailors

5 The Minuet of Lully

6 Courante

7 Entrance of Cléonte

8 Prelude to Act II

9 The Dinner

Richard Strauss’ most successful partnership was with Hugo von Hofmannsthal – the man who wrote the words to Strauss’ best operas. That partnership was tested when Hofmannsthal insisted Strauss collaborate with him on an opera based on Molière’s play Le bourgeois gentilhomme, written for the court of Louis XIV in 1670. Hofmannsthal was fired up by the comic potential of the play, which lampooned Monsieur Jourdain – a middle-class man with aristocratic aspirations. But the opera never came. What emerged, in 1912, was a stilted play with incidental music by Strauss. It proved a failure.

All was not lost however. The project led to one of Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s best operas, Ariadne auf Naxos, which was written as support to the play but later revised to stand on its own. In 1920, Strauss revisited all the music he’d written for various incarnations of the play, and plucked-out the best bits to form a suite. The music is filled with the spirit of the 17th-century, and some of its actual music: 'Minuet' and 'Entrance of Cléonte' reupholster music for Molière’s original production written by Louis XIV’s pet composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Strauss reinvents 17th-century dance forms with very 20th-century harmonic and dramatic alterations. He makes the 'Courante' far more complicated than it needs to be – a reflection of Jourdain’s aspirations – and sends-up a ‘gavotte’ in 'Entrance and Dance of the Taylors'. We hear Jourdain in the Overture – all pretentious and uptight on the trumpet – and in 'The Fencing Master' – prone to bombast on the trombone.

To finish, Strauss delivers a critique of the entire aristocratic class. 'The Dinner' originally accompanied a feast. It tosses quotes from musical history around like a dinner party bore. Among them is a morsel from Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s biggest hit: the opera Der Rosenkavalier.

Note by Andrew Mellor

Richard Strauss

1864–1948 (Germany)

Richard Strauss was born in Munich in 1864, the son of Franz Strauss, a brilliant horn player in the Munich court orchestra; it is therefore perhaps not surprising that some of the composer’s most striking writing is for the French horn. Strauss had his first piano lessons when he was four, and he produced his first composition two years later, but surprisingly he did not attend a music academy; his formal education ending rather at Munich University where he studied philosophy and aesthetics, continuing with his musical training at the same time.

Following the first public performances of his work, he received a commission from Hans von Bülow in 1882 and two years later was appointed Bülow’s Assistant Musical Director at the Meiningen Court Orchestra, the beginning of a career in which Strauss was to conduct many of the world’s great orchestras, in addition to holding positions at opera houses in Munich, Weimar, Berlin and Vienna. While at Munich, he married the singer Pauline de Ahna, for whom he wrote many of his greatest songs.

Strauss’s legacy is to be found in his operas and his magnificent symphonic poems. Scores such as Till Eulenspiegel, Also Sprach Zarathustra, Don Juan and Ein Heldenleben demonstrate his supreme mastery of orchestration; the thoroughly modern operas Salome and Elektra, with their Freudian themes and atonal scoring, are landmarks in the development of 20th-century music, and the neo-Classical Der Rosenkavalier has become one of the most popular operas of the century. Strauss spent his last years in self-imposed exile in Switzerland, waiting to be officially cleared of complicity in the Nazi regime. He died at Garmisch Partenkirchen in 1949, shortly after his widely celebrated 85th birthday.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Richard Wagner orch Leopold Stokowski

Symphonic Synthesis of Tristan and Isolde

✒️ 1865 | ⏰ 35 minutes

1 Vorspiel (Prelude)

2 Love Music

3 Liebestod (Love Death)

In 1859, Richard Wagner finished writing Tristan and Isolde, his most revolutionary opera of all. It tells of the accidental, all-encompassing love between the nobleman Tristan and the princess Isolde.

So strong is this forbidden love that it leads Isolde to the metaphysical conclusion that it can only be realised through death.

For the philosopher Michael Tanner, when witnessing this, we are ‘challenged to believe something, to examine some presuppositions of living at a level which I feel compelled to call religious.’

Wagner’s music does the mind-altering legwork. Much of it is founded on the broad implications of a single four-note chord. The so-called ‘Tristan chord’ is a ‘suspended’ chord – a discord that wants to resolve onto a consonant one, but in this case, can’t. Unable to resolve musically – and by implication, sexually – the chord sets in motion a giant crescendo of passion, longing and angst.

The conductor Leopold Stokowski fashioned an orchestral tone poem from Wagner’s five-hour opera, comprising the work’s orchestral Prelude and Isolde’s Act III Verklärung (her transfiguration, often referred to as her Liebestod – ‘Love Death’) unchanged, and the conductor’s own synthesis of the love music, mainly from Act II.

For Stokowski, the combination of despair and ecstasy in Tristan found its ‘supreme expression’ in the latter two passages. In them, Stokowski wrote,

‘Wagner conceived of sound in a new tonal perspective.’

In tonight’s account we hear the opera’s Prelude: three notes on low strings and then the ‘Tristan chord’, which initiates its own broad arch of longing.

Next, the Love Music describes the night of love that follows the protagonists’ drinking of a love potion. Stokowski’s synthesis of the music removes human voices, occasionally replacing them with instruments (in the first instance, cellos ‘sing’ Tristan’s lines, responded to by Isolde’s violins).

The opera’s tipping point comes in Act III when Isolde, having held the wounded and dying Tristan in her arms, sees their love continuing in death.

Isolde’s Liebestod (Love Death) also resolves the riddle of the Tristan chord. Eventually, the orchestra runs aground on the key of C-sharp major, which in turn forces a standard resolution into G-sharp. Through the portal of the Tristan chord, the music then floats onto B major. This heavenly shift speaks of the bliss of true love, an emotion Wagner claimed never to have experienced.

Note by Andrew Mellor

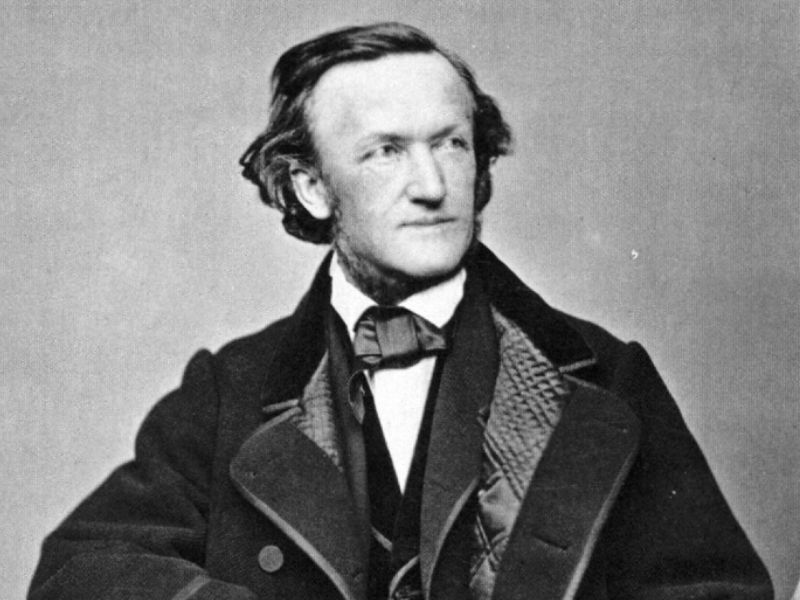

Richard Wagner

1813 (Germany) – 1883 (Italy)

Richard Wagner was born on 22 May 1813 in Leipzig. His musical talent was encouraged at Leipzig’s Nicolaischule and through lessons with Christian Gottlieb Müller. In 1829 he completed his first instrumental compositions, enrolling briefly as a music student at Leipzig University two years later. Wagner married the actress Minna Planer in November 1836, the couple moving from Riga to Paris in 1839 to escape Wagner’s creditors and living there in extreme poverty. Here he completed his opera Rienzi and created another, Der fliegende Holländer. Rienzi proved a big success at its Dresden premiere in October 1842, establishing Wagner’s reputation.

In the 1850s, he began composing his monumental cycle of four Nibelung operas, also completing his ground-breaking opera Tristan and Isolde. His financial difficulties were removed in 1864 by the teenage King Ludwig II, a dedicated Wagnerite who commissioned Der Ring des Nibelungen. Wagner’s comic masterpiece, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg was premiered on Ludwig’s command; the king later funded the building of a new theatre at Bayreuth for the sole performance of Wagner’s works.

For the remaining years of his life, Wagner worked on establishing the festival and composing Parsifal, written specifically for Bayreuth. He died in Venice on 13 February 1883, suffering a heart attack after an impassioned row with his second wife, Cosima.

According to Wagnerian legend, there has been more written about the composer than anybody other than Napoleon and Jesus Christ. Although the claim is inaccurate, it is typical of the myths that have become attached to Wagner’s life and works. The vast scale of his creative output, its revolutionary influence on the development of Western Classical music and the controversial nature of many of his views ensured the development of strong, even fanatical, support both for and against Wagner.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Artist Biographies

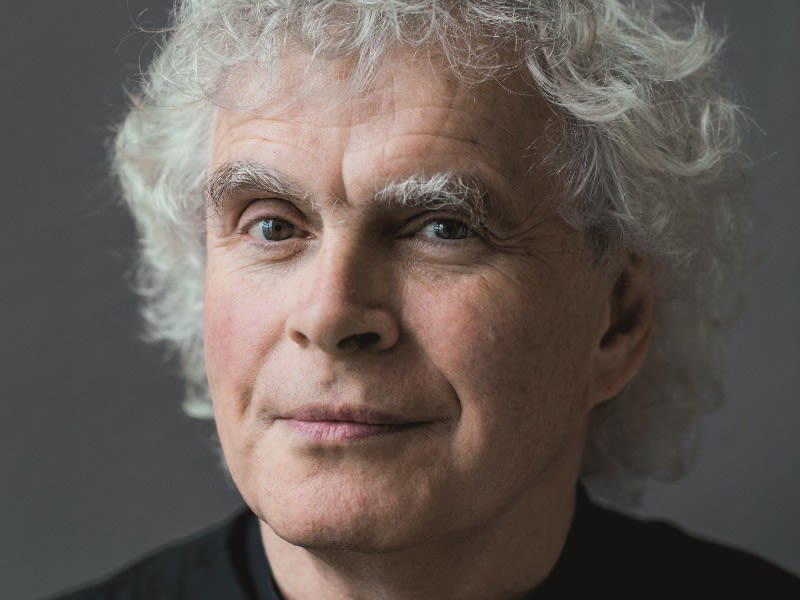

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

From 1980 to 1998, Sir Simon was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. In 2002 he took up the position of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, where he remained until the end of the 2017/18 season. Sir Simon took up the position of Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and will remain there until the 2023/24 season, when he will take the title of Conductor Emeritus. From the 2023/24 season Sir Simon will take up the position of Chief Conductor of the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks in Munich. He is a Principal Artist of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and Founding Patron of Birmingham Contemporary Music Group.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance), Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortilèges, Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker – Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Rachmaninoff's Symphony No 2, Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Natalia Lomeiko

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Second Violins

David Alberman

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Alix Lagasse

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

German Clavijo

Stephen Doman

Carol Ella

Robert Turner

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Jennifer Brown

Noël Bradshaw

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Laure Le Dantec

Amanda Truelove

Double Basses

Hugh Kluger

Colin Paris

Thomas Goodman

Joe Melvin

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Patricia Moynihan

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Olivier Stankiewicz

David Hedley

Cor Anglais

Maxwell Spiers

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bass Clarinet

Katy Ayling

Bassoons

Daniel Jemison

Helen Simons

Contra Bassoon

Dominic Morgan

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Alexander Edmundson

Jonathan Maloney

Daniel Curzon

Trumpets

Jason Evans

Matthew Williams

Niall Keatley

Trombones

Peter Moore

Richard Ward

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Jeremy Cornes

Oliver Yates

Harp

Bryn Lewis

Piano

Elizabeth Burley

Meet the Members of the LSO on our website.

Thank You for Watching