Anton Bruckner

Who was he, and why does his music continue to thrill?

Anton Bruckner

born 1824 (Ansfelden, Austria)

died 1896 (Vienna, Austria)

Bruckner's Musical Life

The Austrian composer, organist and teacher Anton Bruckner was a late bloomer who composed all his major works after the age of 39.

Born in Ansfelden, he studied violin and organ from a young age with his father, the village schoolmaster. After his father’s death in 1837, he became a chorister at the monastery-school of St Florian. His family’s poverty made a musical career impossible; instead, he trained as a schoolteacher. Following positions in Windhaag and Kronstorf, he returned to St Florian, where he taught from 1845 and was organist from 1848. During this period, he composed organ and choral works including a Missa Solemnis (1854). In 1855 he became organist at Linz Cathedral, and embarked on a five-year course in harmony and counterpoint with the Viennese pedagogue Simon Sechter. Later, he studied orchestration with Otto Kitzler, who in 1863 introduced him to Wagner’s music. This proved an enormous creative inspiration and led to his first significant compositions.

Moving to Vienna in 1868, Bruckner took up Sechter’s old post at the Conservatory, and from 1875 also taught at the University of Vienna. During the next 28 years he composed most of his greatest works: these included Symphonies Nos 2 to 9, the String Quintet and the Te Deum. For years he struggled to get his orchestral music performed, particularly after the 1877 premiere of the Third Symphony, which had proved disastrous. Only after the 1884 premiere of the Seventh Symphony in Leipzig did he receive the acclaim he deserved. He continued to compose – and to revise his works obsessively – until his death from heart failure on 11 October 1896. He is buried in the crypt of St Florian.

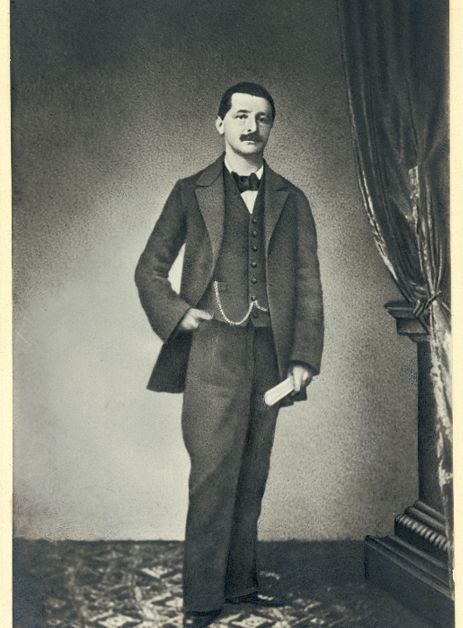

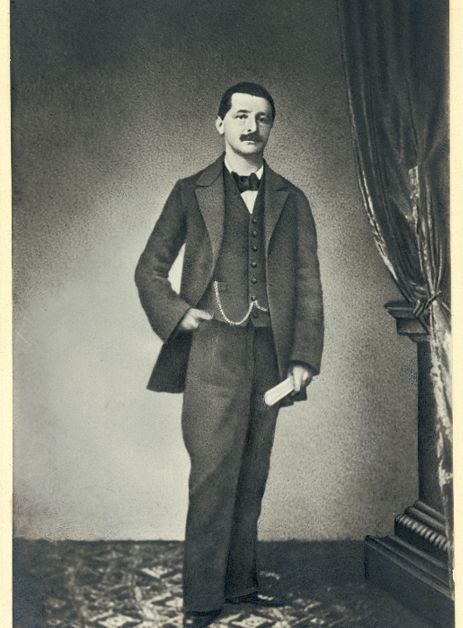

Bruckner, 1854

Bruckner, 1854

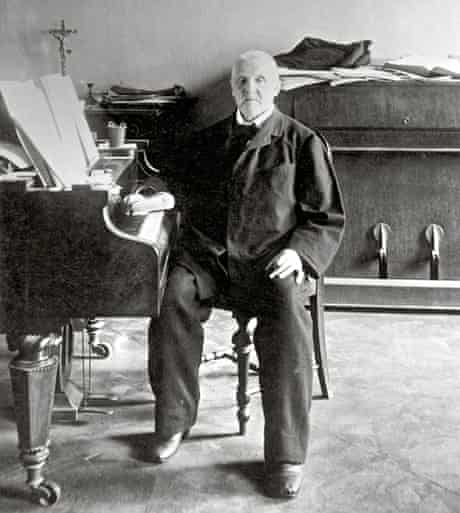

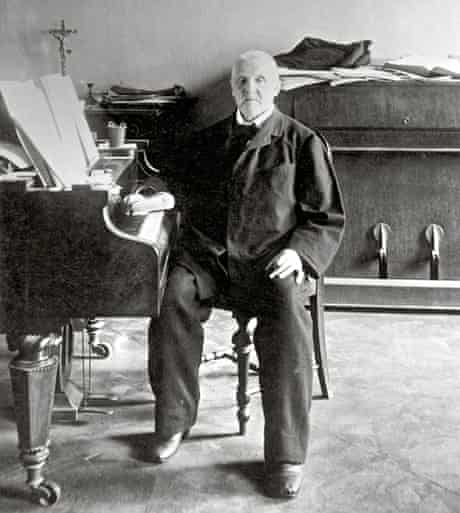

Bruckner, 1894

Bruckner, 1894

Who was Bruckner, Personally?

Bruckner was a strange mixture of sophistication and simplicity. He was a remarkable organ virtuoso and a superb teacher, who could hold his own in conversations with Richard Wagner and Gustav Mahler. However, his behaviour could be naive and eccentric. Attendees at Beethoven’s 1888 exhumation were shocked when Bruckner insisted on handling the skull of the deceased composer. He also counted everything, from bars in sections of his symphonies to windows on buildings.

Bruckner, 1854

It is now thought that Bruckner may have had some form of OCD. He certainly experienced periods of depression, and was hospitalised in 1867, but this did not define him. He never married, but had many friends who thought him excellent company – Mahler testified to his ‘happy disposition’ and ‘childlike, trusting nature’.

His lifelong Catholic faith was of vital importance to him. The writer Max Graf recalled how he once stopped a lecture to pray, and how his face became ‘transfigured, illuminated from within’ as he did so.

Bruckner, 1894

'Cathedrals of Sound'

Bruckner’s best-known works are his Symphonies Nos 3 to 9, and each of them has a distinctive character – something special about them. But they all have common features too: thematic material structured in huge blocks, long passages of intensification (Steigerung), adventurous chromaticism, use of fugues, chorales and Austrian dance rhythms. The massive structures of Bruckner's symphonies have led them to be nicknamed ‘cathedrals of sound’.

Listen To

Symphony No 4, 'Romantic'

A vivid musical depiction of medieval Austria, with exuberant horn calls and a finale full of melodic and dynamic contrasts.

Symphony No 6

Notable for its striking orchestration, including a poignant oboe lament.

Symphony No 8

Perhaps Bruckner’s most impressive achievement – two colossal outer movements book-end a sparkling rustic Scherzo, and a sensual slow movement.

Symphony No 9

Sheer emotional power – the third movement, Bruckner’s ‘farewell to life’, is overwhelming.

Notable Influences and Friends

Composers Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, J S Bach and the First Viennese School (Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven) were among Bruckner’s heroes. Of his contemporaries, it was Richard Wagner whom he admired most. Bruckner dedicated his Third Symphony to him after they spent a convivial (and drunken) evening together. For his part, Wagner considered Bruckner the greatest symphonist since Beethoven.

Richard Wagner

In Vienna, musical loyalties were split between Wagner and Johannes Brahms, and Bruckner’s championship of the former made him enemies. Chief among them was the critic Eduard Hanslick, who repeatedly trashed Bruckner’s symphonies. Brahms himself referred to the compositions as ‘symphonic boa-constrictors’ and to Bruckner as ‘the bumpkin’ – though he admired his work ethic and religious music, and was seen weeping at his funeral.

Despite his difficulties with Brahms’ devotees, Bruckner had a number of distinguished admirers. These included the conductors Hans Richter (the LSO’s first Principal Conductor) and Hermann Levi, and the composers Johann Strauss II, Hugo Wolf and Gustav Mahler. Mahler was a particular fan, and regularly conducted Bruckner’s compositions, to help ‘this glorious art to the triumph it deserves’.

Richard Wagner

Richard Wagner

Bruckner's Influence

The composers Bruckner influenced most were probably Mahler and Schoenberg. Mahler hailed Bruckner as his symphonic forerunner, while Schoenberg was fascinated by his daring harmonic language, which helped to inspire his own experiments with atonality. Scandinavian symphonists Sibelius and Stenhammer were also great admirers.

More recently, the Bruckner's symphonic grandeur has left its mark on film scores by John Williams and Carl Davis. And his music has also played a key role in the careers of many conductors, including Daniel Barenboim, Bernard Haitink, Sir Simon Rattle and Andris Nelsons.

A Cinematic and Literary Legacy

He has made his presence felt in cinema and literature too. Two biopics explore his 1867 nervous breakdown: Ken Russell’s The Strange Affliction of Anton Bruckner (1990) and Jan Schmidt-Garre’s Bruckner’s Decision (1995). His music is used to powerful effect in films such as Luchino Visconti’s historical melodrama Senso (1954) and Ingmar Bergman’s valedictory Saraband (2003).

Writers as varied as Gabriel García Márquez, Elfriede Jelinek, Stan Barstow, Rabih Alameddine and Douglas Kennedy refer to his life and works in their fiction – Kennedy’s description of the impact of the Ninth Symphony in his novel Leaving the World is particularly powerful.

Other Works to Listen Out For

Te Deum

Considered by Bruckner to be one of his best pieces, and full of theatrical excitement. It reflects how sacred music was also a key part of his oeuvre.

String Quintet

A lighter side to Bruckner's character, with a beautiful slow movement and a few surprises.

Mass in F minor

The third of three large-scale masses composed in Linz and Vienna, which left Brahms applauding so vehemently at a Vienna performance that Bruckner even came up to thank him.

Why Bruckner's Music Continues to Thrill

His structural, harmonic and rhythmic invention makes every one of his mature compositions an epic adventure. And his music has an emotional depth and honesty that evokes a profound response in many listeners, whether or not they share his religious beliefs.

They are indeed among the most exciting and moving compositions ever written for orchestra.

‘A sense of the awe-inspiring, born of the naked wonder, fear and delight of elemental humanity confronted by the mysterious beauty and power of nature and the vast riddle of the cosmos.’

This Sunday: Hear Bruckner Live

Bruckner's Journey to the 'Romantic' Symphony

Sunday 19 September 7pm, Barbican

Sir Simon Rattle takes a journey of discovery around the magnificent Fourth ‘Romantic’ Symphony, stepping inside Bruckner’s workshop to explore some of the music that didn’t make the final cut. Then he conducts the entire Symphony in all its splendour: music that never gets any less stirring, and has never sounded so fresh.

Composer profile by Kate Hopkins

Kate Hopkins writes on classical music and on literature. Her work has featured in publications including The Wagner Journal, NB Magazine and programme books for The Royal Opera, ENO and WNO.