London Symphony Orchestra Spring 2021

Barber, Harrison,

Varèse & Ravel

Welcome and Thank You for Watching

Whilst we are unable to come together with audiences at our Barbican home, we are pleased to continue releasing a programme of online content and streamed broadcasts, making music available for everyone to enjoy digitally. A warm welcome to the numerous conductors and soloists joining us, among them many firm friends and regular collaborators with the Orchestra.

It is a pleasure to invite you to watch and listen today online, and we extend thanks to our broadcast partner Medici TV for streaming this concert live. I hope you enjoy the performance, and look forward to welcoming you back in person when we are able to re-open our doors.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Sir Simon Rattle and Barbara Hannigan travel from Ravel to Lou Harrison, by way of Varèse and Samuel Barber – four very different modern masters, each testing the boundaries of memory and myth.

Barber, Harrison, Varèse & Ravel

Samuel Barber Knoxville: Summer of 1915*

Lou Harrison Song of Quetzalcoatl

Interval (20 minutes)

Edgard Varèse Offrandes

Maurice Ravel Mother Goose – Ballet

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

Barbara Hannigan soprano / soprano & conductor*

Rachel Leach presenter

London Symphony Orchestra

This performance is broadcast live on Medici TV on Sunday 21 March 2021, recorded at LSO St Luke's in COVID-19 secure conditions.

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra, allow us to perform together again on stage and to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO’s return to work is supported by DnaNudge.

Generously supported by the Weston Culture Fund.

Share Your Thoughts

We always want you to have a great experience, however you watch the LSO. Please do take a few moments at the end to let us know what you thought of the streamed concert and digital programme. Just click 'Share Your Thoughts' in the navigation menu, or click here to fill out the survey.

Samuel Barber

Knoxville: Summer of 1915 Op 24

✒️1947 | ⏰15 minutes

Barbara Hannigan soprano & conductor

Knoxville: Summer of 1915 was written at the behest of the American soprano, Eleanor Steber, who asked Samuel Barber to compose a new work for soprano and orchestra. Barber turned to a text by the American writer, James Agee, which captures memories of Agee’s childhood in his hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee. Written as though through the eyes of a six-year-old child, the text gives the impression of sweet, unguarded innocence, a charming depiction of the people that made up the young Agee’s small world. But buried within the words there is also a deep sense of nostalgia, of a lost era that the adult Agee cannot reclaim. This complex mix of time and perspective creates an overlapping, impressionistic vision of this hazy summer, as fluid as Agee’s own memories. The text was written in one great improvisatory swirl, and Barber’s music follows suit, growing organically from its opening cells to evolve into a single movement that Barber would later describe as a ‘lyric rhapsody’.

The three-note motif first sung by the soprano at the very opening acts as the work’s central pivot, disappearing and resurfacing amidst the changing textures, recognisable but always reinterpreted. At the opening, the motif is poised and still, winding through the dulcet woodwind interplay, which depicts a cool summer evening. But it is not long before this germinal cell is transformed into a highly charged, aggressive motif that is taken on by the full orchestra, shattering the peace just as street noises disrupt the evening calm in Agee’s poem. Indeed, although the work is ultimately one of contentment and calm, the final lines of the poem introduce a nagging doubt: that his parents can never tell him how or what he should grow up to become. In the final few bars, this sense of unease and quiet solitude returns with the rocking motion first heard in the opening, as though Agee were reluctant to leave the state of security and comfort that his parents provided.

Note by Jo Kirkbride

Samuel Barber

1910–81 (US)

Bettmann/Corbis

Bettmann/Corbis

Given the enormous success he enjoyed during his career, it is puzzling that Samuel Barber is now remembered primarily for just one work – his Adagio for Strings (1938). His catalogue of music, though not as extensive as some of his contemporaries, extends from solo piano music and instrumental chamber works to symphonies, concertos and operas. He was twice awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music, in addition to the American Prix de Rome, and in 1966 he was commissioned to write a new opera to mark the opening of the Metropolitan Opera’s new home at the Lincoln Center (the production was a flop, but this was largely thanks to Zeffirelli’s direction, rather than Barber’s music).

Barber’s relative neglect from the 20th-century canon probably owes much to his musical style. While Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School forged new harmonic paths through atonality and serialism, and Igor Stravinsky explored bold new levels of dissonance, rhythmic vitality and texture, Barber seemed content to follow his own path, one which owed more to the dying strains of Romanticism than to the radical new soundworld of the 20th century. That is not to say that Barber’s music is not innovative and dramatic, nor that his often complex and dissonant harmonies can be considered ordinary, but the rich, full textures of his works with their predilection for sweeping, generous melodies sets them apart from many of the more experimental trends of his age.

Composer profile by Jo Kirkbride

Lou Harrison

Song of Quetzalcoatl

✒️1941 | ⏰7 minutes

Like most magpies, Lou Harrison is attracted to found objects, and many of his works aim to transform ‘found sounds’ into musical scores. This reveals itself in a predilection for percussive instruments, particularly in his early works, but much of his music is also inspired by visual cues. Artwork, photography and historical artefacts – Harrison has translated all of these things into his scores, often using unfamiliar or ‘junk yard’ instruments to best capture their quirks. His Song of Quetzalcoatl, composed when he was just 24 years old, was inspired by an extract from a full-colour reproduction of Mexican codices that Harrison came to own while living and studying in San Francisco. Among its pages, Harrison found an image of a Feathered Serpent — or Quetzalcoatl — which was regarded by the Aztecs as the God of wind, air and learning. The song Harrison composed in its honour manages to capture both the startling, iridescent colours of the Aztec imagery but also its unmistakeably ritualistic overtones, which pulse through the work with a quietly hypnotic effect.

Song of Quetzalcoatl was premiered as part of the iconic Californian concerts series that Harrison staged with fellow composer John Cage from 1941–42, and was pioneering in its time for its development of the percussion ensemble. Among the bewildering array of instruments Harrison calls for are glasses, wood blocks, sistrums (Egyptian shakers), dragon’s mouth temple blocks, cowbells, wooden rattles, a guiro, triangle, gong, tam-tam and a huge assortment of drums of varying shapes and sizes — all played by four percussionists. But the ensemble is never let loose or allowed to run out of control. There is a calm precision to Harrison’s repeated, ostinato patterns, even in the work’s more spirited central section. It is dance-like, entrancing and irresistible, the lingering sense of awe and transfixion as the work ebbs away much as Harrison must have felt when stumbling across the astonishing Aztec artwork.

Note by Jo Kirkbride

Lou Harrison

1917–2003 (US)

© Betty Freeman

© Betty Freeman

American-born Lou Harrison was one of the 20th century’s musical magpies, whose interests were as wide-ranging as the instruments he employed. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Harrison did not study at a conservatoire or receive formal training in the western musical tradition. Instead, he took Henry Cowell’s ‘Music of the World’s Peoples’ course at the New School for Social Research in New York, and through Cowell’s tutelage developed a strong interest in the music of Indonesian, Native American, Mexican and Cantonese cultures.

Cowell placed a huge emphasis on melody and rhythm — arguing that western music had become too focused on harmony as the be-all and end-all — and encouraged Harrison to work with small, germinal cells which could be transmuted, developed and adapted to create broader, complex patterns. This manifests itself in Harrison’s music as a kind of physicality; it is living, vibrant and grounded in a dance-like connection with the human body. And although he would later synthesise these diverse influences with an interest in the twelve-tone music of Arnold Schoenberg, with whom he studied while living in Los Angeles, his attitude remained broad and open. If the sound of something pleased him, he would use it. As he once commented in a BBC interview: ‘Don't put hybrids down … because there isn't anything else.’

Composer profile by Jo Kirkbride

Short interval (20 minutes).

Stay tuned to hear from Barbara Hannigan

Edgard Varèse

Offrandes

✒️1921 | ⏰9 minutes

Barbara Hannigan soprano

In 1921, six years after emigrating to New York, Edgard Varèse formed the International Composers Guild (ICG) with his new friend, the harpist, composer and conductor Carlos Salzedo. The ICG’s self-declared mission was to create a new audience for contemporary music, its motto being ‘New Ears for New Music and New Music for New Ears’. Among other ventures, the ICG held an annual concert series which was restricted to performances of music that had not yet been heard. In time, this would include music by Webern, Ravel, Satie, Bartók and Poulenc, among others, and it was under these auspices that Varèse composed and premiered some of his most important works. The first two years of the series saw Varèse premiere his chamber works Offrandes (1921), Hyperprism (1922), Octandre (1923), and Intégrales (1923).

Offrandes was inspired by a recent trip to Mexico and sets two surrealist texts by the Chilean poet Vincent Huidobro and the Mexican poet José Juan Tablada. Varèse called it ‘a very small-scale piece, a purely intimate work’, but it is only really small-scale by Varèse’s standards. The chamber ensemble which accompanies the solo soprano includes a full complement of strings, wind, brass, harp and eight percussion parts. Russian composer Igor Stravinsky is said to have called one of the searing moments in its second movement ‘the most extraordinary noise in all of Varèse.’ In fact, there is more than a hint of Stravinsky here, in the blurred lines between music and noise, which shift in and out of melody, fragments grouping and regrouping, never quite coalescing for long enough to seem rooted and secure. The poem underlying the first movement, Chanson de là-haut, depicts the River Seine after dark, with allusions to Charles Ives’ musical work The Unanswered Question (1910) – which depicts New York by night – in the guttural, fragmentary trumpet fanfare that calls out into the abyss. Elsewhere, we hear traces of Claude Debussy and even Hector Berlioz in the occasional orchestral shimmer, or glimpse of rich, vocal warmth. But nothing is quite as it seems and nothing stays stationary for long. It is as though Varèse were refracting all these disparate influences from his past through a lens and asking us to hear them anew, earthy and unmasked.

Note by Jo Kirkbride

Edgard Varèse

1883 (France)–1965 (US)

Edgard Varèse’s career can be carved into two parts: his early works, almost all of which were destroyed in a warehouse fire in 1918, and those that came afterwards, composed for the most part during Varèse’s years in America. What is striking is the clear stylistic divide between the two, as though the fire had purged Varèse of his earlier inclinations and given him carte blanche to reinvent himself anew. Varèse’s early career was influenced by the composers with whom he studied in Paris and Berlin: Erik Satie, Richard Strauss and Claude Debussy (although it is thought that just one score – the song Un grand sommeil noir from 1906 – survives from these years).

When Varèse moved to New York in 1915, however, his vision of music changed altogether. He came to understand music as ‘organised sound’, and to conceive his works as ‘moving bodies of sound in space’, a definition that he would apply to the ground-breaking series of works that make up his relatively tiny oeuvre from here on. Altogether, they make up little more than three hours of music. They include the seminal Ionisation (1931) for 13 percussionists and sirens and Déserts (1954) which was unprecedented in its bringing together of orchestral and electronic music. ‘The dead govern us’, Varèse once lamented, ‘their lives, their laws, their traditions weigh us down, poison and enervate us.’ In turn, he resolved to forge a new path with his music, determined to be ‘absolument moderne.’ Dissonant, visceral and with rhythm and timbre as its guiding principles, Varèse’s music never fell short of this ambition.

Composer profile by Jo Kirkbride

Texts

1 Song from On High

The Seine is asleep in the shadow of its bridges.

I watch Earth spinning,

And I sound my trumpet

Toward all the seas.

On the pathway of her perfume

All the bees and all the words depart,

Queen of the Polar Dawns,

Rose of the Winds that Autumn withers!

In my head a bird sings all year long.

Poem by Vincente Huidobro

2 The Southern Cross

Women with gestures of madrepores

Have lips and hair as red as orchids.

The monkeys at the pole are albinos,

Amber and snow, and frisk

Dressed in the aurora borealis.

In the sky there is a sign,

Oleomargarine.

Here is the quinine tree

And the Virgin of the Sorrows.

The Zodiac revolves in the night of yellow fever. The rain holds the tropics in a crystal cage.

It is the hour to stride over the dusk

Like a Zebra toward the Island of Yesterday

Where the murdered women wake.

Poem by José Juan Tablada

Offrandes

Music by Edgard Varèse

Copyright © 1921 by Casa Ricordi Srl

All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured Displayed and reproduced by kind permission of Hal Leonard Europe Srl obo Casa Ricordi Srl

Maurice Ravel

Mother Goose Ballet

✒️1910–11 | ⏰30 minutes

Prelude

Spinning-Wheel Dance and Scene

Sleeping Beauty’s Pavane

Conversations Between Beauty and the Beast

Tom Thumb

The Plain Girl, Empress of the Pagodas

The Fairy Garden

The lush, impressionistic quality that we regard with such wonder in Maurice Ravel’s music today did not always win him favour with listeners. During several years at the Conservatoire in Paris, he failed to win the prestigious prize the Prix de Rome at every attempt – his music being considered too avant-garde and too radical for the conservative judging panel. Despite looking set to become one of the institution’s great stars, Ravel was dismissed from the Conservatoire in 1895. Two years later, he returned to the Conservatoire once more, this time to study composition with Gabriel Fauré and counterpoint with André Gédalge, and in the years that followed he learned to combine his love for the piano with his growing proficiency as a composer. Many of his major works, particularly in his early years, would be composed for the piano, and later orchestrated for larger ensembles.

Ma mère l'Oye (1910–11), or Mother Goose, was one of these works, composed in 1910 as a piano duet for children, before being orchestrated and expanded into a ballet the following year. The original duet was written for the two young children of Ravel’s fellow artist, Cyprian Godebski, and was based upon a number of their favourite fairy tales – including the stories of Mother Goose. Unfortunately, the music proved too difficult for the Godebski children to play and it had to be performed by two young Conservatoire pupils at the Paris premiere. The original suite comprises five movements – 'Pavane of Little Sleeping Beauty', 'Little Tom Thumb', 'Empress of the Pagodas', 'Beauty and the Beast' and 'The Fairy Garden' – but Ravel also added a Prelude, 'Spinning Wheel Dance' and a number of small interludes when he published the work as a ballet. The music is characterised by its restrained emotion and simple, uncluttered orchestral style. As Ravel later explained: ‘The idea of evoking in these pieces the poetry of childhood naturally led me to simplify my style and to refine my means of expression.’ As a result, the music has an innocent, magical charm about it, a marked contrast to the grandeur of his more lavish orchestral scores.

Note by Jo Kirkbride

Maurice Ravel

1875–1937 (France)

Ravel himself knew that he was not the most prolific of composers. ‘I did my work slowly, drop by drop. I tore it out of me by pieces,’ he said. There are no symphonies in Ravel’s oeuvre, and only two operas, and although we often think of his music as rich and picturesque like, say, Claude Debussy, Ravel conceived most of his music on the smallest of scales. Even his orchestral works and ballets often grew out of pieces for piano.

But from these small kernels Ravel had the ability to create colour and texture like no other. He was a master of orchestration, with a fastidious eye for detail and a keen awareness of both the capabilities and the limitations of each instrument. Though he is often categorised as an ‘impressionist’ (a label he disputed), thanks to the sweeping colours and textures of his scores, and their shifting, ambiguous harmonies, there is nothing vague or imprecise about his music. Ravel drew his inspiration from composers of previous centuries, the likes of Jean-Philippe Rameau, François Couperin, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Joseph Haydn, and considered himself first and foremost a Classicist, a master of precision and invention. He held melody in the highest regard, and whether composing his grand orchestral masterpieces like Daphnis and Chloe and Boléro, the fiendishly difficult solo piano works such as Gaspard de la nuit, or the deceptively simply Pavane pour une infante défunte, this unswerving commitment to melody shines through.

Composer profile by Jo Kirkbride

Artist Biographies

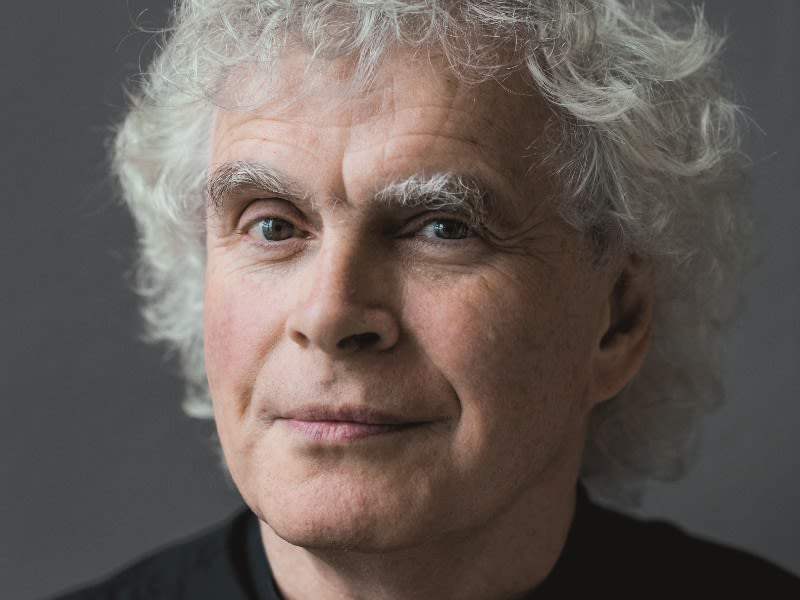

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

Sir Simon Rattle was born in Liverpool and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1980 to 1998, he was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. He moved to Berlin in 2002 and held the positions of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic until he stepped down in 2018. Sir Simon became Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and spent the 2017/18 season at the helm of both ensembles.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance), Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortilèges, Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker – Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Rachmaninoff's Symphony No 2, Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

Barbara Hannigan

soprano & conductor

Embodying music with an unparalleled dramatic sensibility, soprano and conductor Barbara Hannigan is an artist at the forefront of creation. Her artistic colleagues include Sir Simon Rattle, Sasha Waltz, Kent Nagano, Vladimir Jurowski, John Zorn, Andreas Kriegenburg, Andris Nelsons, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Christoph Marthaler, Sir Antonio Pappano, Katie Mitchell, Kirill Petrenko and Krzysztof Warlikowski.

As a singer and conductor the Canadian musician has shown a profound commitment to the music of our time and has given the world premiere performances of over 85 new creations. Hannigan has collaborated extensively with composers including John Zorn, Salvatore Sciarrino, Pascal Dusapin, Brett Dean, Sir George Benjamin and Hans Abrahamsen, and the late Pierre Boulez, Henri Dutilleux, György Ligeti, Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Barry.

Last season marked the beginning of her Principal Guest Conductor role at Gothenburg Symphony. She also had conducting and singing engagements with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Münchner Philharmoniker, and was artist in residence at Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. Hannigan premiered the role of Gerda in the Bayerische Staatsoper’s production of Hans Abrahamsen’s The Snow Queen.

Hannigan’s album as both singer and conductor, Crazy Girl Crazy (2017), won the 2018 Grammy Award for Best Classical Solo Vocal album. Other recent albums include Vienna: fin de siècle and Satie’s Socrate, both with pianist Reinbert de Leeuw. In spring 2020 she released her latest album on Alpha Classics, La Passione, with works by Nono, Haydn and Grisey.

In 2020 Barbara launched Momentum: Our Future, Now, a major international initiative driven by leading artists supporting younger colleagues. She also continues her acclaimed work with Equilibrium Young Artists mentoring initiative, which she launched in 2017. May 2021 will see Hannigan awarded the prestigious Léonie Sonning Music Prize.

Rachel Leach

presenter

Rachel Leach was born in Sheffield. She studied composition with Simon Bainbridge, Robert Saxton and Louis Andreissen. Her music has been recorded by NMC and published by Faber. She has won several awards including, with English Touring Opera, the RPS award for Best Education Project 2009 for One Day, Two Dawns.

Rachel has worked within the education departments of most of the UK’s orchestras and opera companies. The majority of her work is for the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Rachel has written well over 20 pieces for LSO Discovery and 15 community operas, including seven for ETO.

Alongside this she is increasingly in demand as a concert presenter. She is the presenter of the LSO Discovery Friday Lunchtime concert series and regularly presents children’s concerts and pre-concert events for the LSO, LPO, BBC Proms, Royal College of Music and Wigmore Hall.

In Spring 2013 Rachel was awarded Honorary Membership of the RCM in recognition of her education work.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Carmine Lauri

Clare Duckworth

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Second Violins

David Alberman

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

David Ballesteros

Naoko Keatley

Iwona Muszynska

Csilla Pogany

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Rachel Roberts

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

German Clavijo

Stephen Doman

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Jennifer Brown

Noel Bradshaw

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Double Basses

Hugh Kluger

Colin Paris

Joe Melvin

José Moreira

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Patricia Moynihan

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Rosie Jenkins

Cor Anglais

Maxwell Spiers

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Shelly Organ

Contra Bassoon

Dominic Morgan

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Trumpet

Jason Evans

Trombone

Peter Moore

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Tom Edwards

Jeremy Cornes

Paul Stoneman

Jacob Brown

Matthew Farthing

Harp

Bryn Lewis

Celeste

Elizabeth Burley

Meet the Members of the LSO on our website

Thank You for Watching