Bartók

Concerto for Orchestra

Georg Solti conductor

Béla Bartók

Concerto for Orchestra

1943, rev 1945

1. Introduzione (Introduction)

2. Giuoco delle coppie (Game of Pairs)

3. Elegia (Elegy)

4. Intermezzo Interrotto (Interupted Intermezzo)

5. Finale

A colourful showpiece, and probably the most popular of Bartók’s orchestral works, the Concerto for Orchestra was composed in the USA, where Bartók and his wife had moved in 1940 to escape fascism and war in their native Hungary. At this time, Bartok’s career, health and finances were in decline. His 60th birthday in 1941 had passed by unhonoured in his adopted home country.

While in hospital with suspected tuberculosis in May 1943, Bartók was visited by the conductor and patron Serge Koussevitzky, who offered him $1,000 for a new orchestral piece. Bartók wrote most of the work over two months while staying at a ‘cure cottage’ near Lake Saranac in upstate New York, shielded from the hubbub of New York City.

Image © Steve Johnson

Bartók may have deliberately set out to avoid writing a ‘symphony’, regarding that as an outdated form. While the concerto model had existed for at least two centuries, the idea of a concerto for orchestra (as opposed to a solo instrument, or a small core of instruments, plus orchestra) was quite new. The aim was ‘to treat the single instruments or instrumental groups in a concertant or soloistic manner’. This gives rise to a rich variety of orchestral textures. Bartók noted:

‘The general mood of the work represents, apart from the jesting second movement, a gradual transition from the sternness of the first movement and the lugubrious death-song of the third, to the life-assertion of the last one.'

After the ‘Introduction’ comes the ‘jesting’ ‘Game of Pairs’ in which, in the manner of Noah’s Ark, instruments enter two by two, playing at fixed intervals apart: bassoons in sixths, oboes in thirds, clarinets in sevenths, and so on.

The central ‘death-song’ features elements of Bartók’s ‘Night Music’ writing: nocturnal, magical, occasionally disturbing. (It’s hard to believe Bernard Herrmann didn’t borrow elements of this for his Hitchcock film scores.) The uncharacteristically nostalgic, lyrical tune on violas in the fourth movement quotes a popular nationalistic song:

‘You are lovely, you are beautiful, Hungary.’

A whooping call on horns opens the finale, a fizzing series of dances in a final fling that shows off the orchestra’s flair and virtuosity as individuals and as a collective.

Image © Paweł Czerwiński

Not the Original, but the Best?

Bartók didn’t invent the idea of a ‘Concerto for Orchestra’. Before his 1943 work came examples by Hindemith (1925) and the Italians Malipiero (1931), Petrassi (1934) and Casella (1937), as well as Bartók’s friend and fellow folk-song collector, Zoltán Kodály. The late André Previn, a much-loved collaborator of the LSO, wrote his Concerto for Orchestra in 2016. (Its second movement, ‘Duets’, could even be a response to Bartók’s ‘Game of Pairs’.)

Image: Andre Previn © Lillian Birnbaum

May the Fourths Be With You

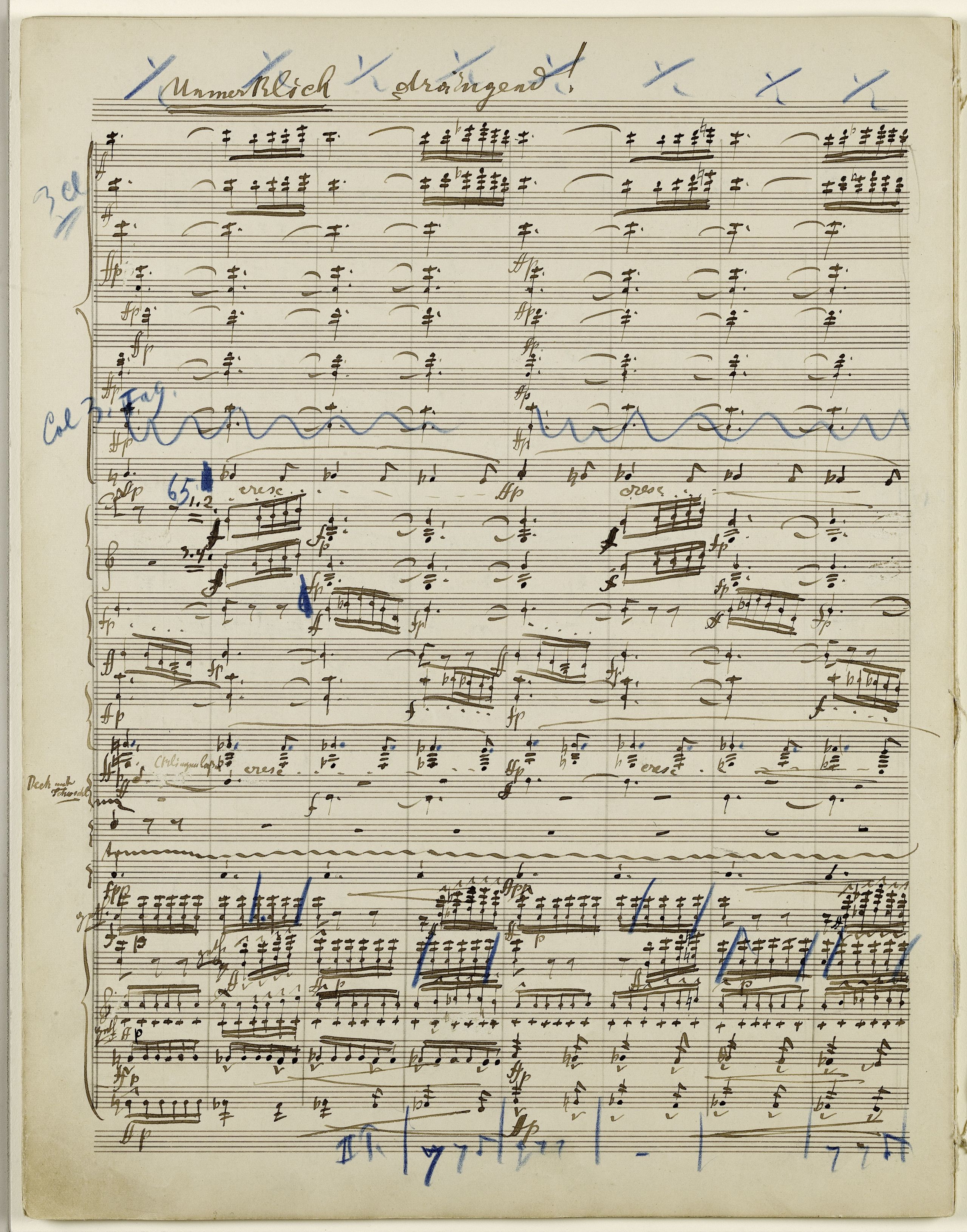

The eerie, unstable effect created at the opening of Bartók’s Concerto comes from the chain of fourths in the cellos and basses (the ‘fourth’ refers to the number of stepwise pitch intervals along a standard scale). Standard harmony until the end of the 19th century had been based on thirds and fifths. Other composers who explored melodies and harmonies based on fourths include Mahler, Schoenberg, his pupil Berg, Scriabin and Ravel.

Image: Mahler's 2nd Symphony © Sotheby's

Take Five

Five is an unusual number of movements for a concerto or symphony (which generally have three or four movements.) But symphonies that go that extra mile are Beethoven’s Sixth (the ‘Pastoral’), Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and Mahler’s Seventh (which has two ‘Night Music’ movements).

Drugs Buy Music

Bartók was reported to be one of the first civilians (as opposed to the military) to be treated with penicillin. ASCAP (the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) underwrote all Bartók’s medical and recuperation costs, to the tune of $16,000. The extra two-and-a-half years this bought him allowed him to compose not only the Concerto for Orchestra, but also the Sonata for Solo Violin, Piano Concerto No 3 and Viola Concerto.

Image © Hal Gatewood

Béla Bartók

1881–1945

Bartók, along with his contemporary Zoltán Kodály, built up a Hungarian national art-music that drew heavily on its rich folk tradition. After studying piano and composition at the Budapest Academy he embarked with Kodály on a series of folk-song collecting tours, recording, transcribing and classifying music from Hungary, Transylvania, and even North Africa and Turkey. Folk and folk-like material became central to his style, though Strauss had been an early influence, as, later, had Debussy, but it was the ballets of Stravinsky that led Bartók to his own ballets, The Wooden Prince (1914–17) and The Miraculous Mandarin (1918–19, orch 1924, later revised).

From 1907 to 1934 Bartók taught piano at the Budapest Academy, during which time he performed regularly in Hungary and abroad as a concert pianist. Objecting to Hungary’s alliance with the Nazis (though he wasn’t Jewish himself), Bartók fled to the USA in 1940. Here, suffering from financial and health problems, he wrote his Concerto for Orchestra and other works.

Notes & composer profile by Edward Bhesania

Edward Bhesania is a writer and editor who reviews for The Strad and The Stage. He has also written for The Observer, BBC Music Magazine, International Piano, The Tablet and Country Life.

Sir Georg Solti

1912–97

Hungarian-born British conductor and pianist Sir Georg Solti was one of the most highly regarded conductors of the second half of the 20th century.

Solti studied at the Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest with Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály. At 18 he joined the coaching staff of the Budapest Opera and made his conducting debut there in 1938. He won the Geneva International Piano Competition in 1942. After the war he became Music Director of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich (1946–52), the Frankfurt Opera (1952–60), and the Royal Opera at Covent Garden (1961–71). He assumed British citizenship in 1972 and was knighted that same year.

From 1969 to 1991 he was Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, reestablishing that orchestra’s international reputation. He was chief conductor of the Orchestra of Paris (1972–75) and acted as musical adviser to the Paris Opéra from 1971 to 1973. He served as the principal conductor and artistic director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra from 1979 to 1983.

As a conductor Solti was best known for his dynamic and deeply felt interpretations of operas, symphonies, and other large-scale works. He was particularly notable for his sharp attention to musical detail and his ability to evoke a wide range of tonal colours from an orchestra. He made many highly praised recordings from the late 1940s as both conductor and solo performer. In 1958–65 Solti made the highly acclaimed first complete set of recordings of Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle, released in 1966. During his career Solti won 32 Grammy Awards, more than any other performer in recording history.

Biography source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

The LSO was established in 1904 and has a unique ethos. As a musical collective, it is built on artistic ownership and partnership. With an inimitable signature sound, the LSO’s mission is to bring the greatest music to the greatest number of people.

The LSO has been the only Resident Orchestra at the Barbican Centre in the City of London since it opened in 1982, giving 70 symphonic concerts there every year. The Orchestra works with a family of artists that includes some of the world’s greatest conductors – Sir Simon Rattle as Music Director, Principal Guest Conductors Gianandrea Noseda and François-Xavier Roth, and Michael Tilson Thomas as Conductor Laureate.

Through LSO Discovery, it is a pioneer of music education, offering musical experiences to 60,000 people every year at its music education centre LSO St Luke’s on Old Street, across East London and further afield.

The LSO strives to embrace new digital technologies in order to broaden its reach, and with the formation of its own record label LSO Live in 1999 it pioneered a revolution in recording live orchestral music. With a discography spanning many genres and including some of the most iconic recordings ever made the LSO is now the most recorded and listened to orchestra in the world, regularly reaching over 3,500,000 people worldwide each month on Spotify and beyond. The Orchestra continues to innovate through partnerships with market-leading tech companies, as well as initiatives such as LSO Play. The LSO is a highly successful creative enterprise, with 80% of all funding self-generated.

Image: Ranald Mackechnie

Always Playing

While we are unable to perform at the Barbican Centre and our other favourite venues around the world, we are determined to keep playing!

Join us online for a programme of full-length concerts twice a week, artist interviews, playlists to keep you motivated at home, activities to keep young music fans busy and much much more!

Visit lso.co.uk/alwaysplaying for the latest announcements.

In the mean time:

- Subscribe to our YouTube channel where you can watch over 500 videos.

- Follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter for great quizzes, listening suggestions and more.

- Sign up to our email list to be the first to hear about our new programme.

Sunday 19 April 7pm BST

Bernstein Prelude, Fugue and Riffs

Bartók Hungarian Peasant Songs

Szymanowksi Harnasie

Stravinsky Ebony Concerto

Golijov Nazareno

Bernstein Prelude, Fugue and Riffs

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

Click here for more information and details on how to stream.