London Symphony Orchestra

Beethoven Piano Concertos

Welcome and Thank You for Watching

Whilst we are unable to come together with audiences at our Barbican home, we are pleased to continue releasing a programme of online content and streamed broadcasts, making music available for everyone to enjoy digitally. We have been delighted to welcome numerous conductors and soloists, among them many firm friends and regular collaborators with the Orchestra, along with members of our family of conductors.

With this series of Piano Concertos, recorded in December 2020 and originally broadcast on DG Stage, we concluded our celebrations of the 250th anniversary of Beethoven's birth. It was a great pleasure to be joined by soloist Krystian Zimerman, with whom the Orchestra and Sir Simon Rattle have enjoyed a number of rewarding collaborations in recent years.

I hope you enjoy the performances, and look forward to welcoming you back in person when we are able to re-open our doors.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Renowned Polish pianist Krystian Zimerman joins forces with the LSO and Sir Simon Rattle for a three-concert cycle of Beethoven's five piano concertos.

This digital programme features notes for all three concerts across the weekend, listed in the order they will be broadcast. You can use the menu to navigate.

Saturday 24 April 7pm

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 3

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 1

Sunday 25 April 2pm

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 2

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 4

Sunday 25 April 7pm

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 5 'Emperor'

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

Krystian Zimerman piano

London Symphony Orchestra

These concerts are broadcast free on the LSO's Youtube channel. Each concert is available to watch on demand for 48 hours after broadcast.

Recorded at LSO St Luke's in December 2020 in COVID-19 secure conditions.

The Complete Piano Concertos album will be released by Deutsche Grammophon on 9 July 2021. Listen to pre-release tracks now.

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra, allow us to perform together again on stage and to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO’s return to work is supported by DnaNudge.

Generously supported by the Weston Culture Fund.

Share Your Thoughts

We always want you to have a great experience, however you watch the LSO. Please do take a few moments at the end to let us know what you thought of the streamed concert and digital programme. Just click 'Share Your Thoughts' in the navigation menu.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No 3

✒️ 1800, rev 1804 | ⏰ 33 minutes

1 Allegro con brio

2 Largo

3 Rondo: Allegro

By the time his first two piano concertos were published in their final forms in 1801, Beethoven had long been at work on their successor, a piece which, he claimed, was at ‘a new and higher level’. Indeed, his intention had been to perform it at a benefit concert at the Burgtheater in April 1800, but in the event it was not ready and one of the earlier concertos was substituted. It was not until 5 April 1803 that the Third was finally premiered, at a concert in the Theater an der Wien which also included the first performances of his Second Symphony and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives. Even then the piano part had not been written down: a fellow composer who turned pages for Beethoven found that they consisted of ‘almost nothing but empty leaves; at the most on one page or the other a few Egyptian hieroglyphs, wholly unintelligible to me, scribbled down to serve as clues for him’.

The concert was a moderate success. Critics had little to say about the new concerto other than that Beethoven’s playing was rather disappointing. Yet even those familiar with the work’s predecessors would surely have noticed that Beethoven’s pride in it was justified. This is a more sophisticated, original and weighty piece than the first two concertos, one that reflects the changes that were occurring in the composer’s style as he moved from early-period promise and brilliance to middle-period mastery and increasing individuality.

Beethoven’s musical personality is stamped all over the Third Piano Concerto, most unmistakably in its choice of key. Almost from the beginning of his career, Beethoven had turned to C minor to express some of his strongest sentiments, and by the time of this concerto he had already written several powerful works in that key, including the famous ‘Pathétique’ Piano Sonata. The inspiration for these Beethovenian emotional colourings was probably the prolific composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whose C minor Fantasy and Sonata for solo piano and Piano Concerto No 24 provide clear anticipations of Beethoven’s C minor mood. Mozart’s concerto, a work Beethoven is known to have admired, also appears to have provided some formal pointers.

First Movement

That model is acknowledged in the opening bars of Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto, where, as in Mozart's concerto, a quiet theme is stated by the strings in unison. This is the start of what turns out to be an unusually long orchestral exposition, but after an assertive entry it is the soloist who delineates the movement’s formal scheme, as climactic trills and precipitous downward scales noisily signal the respective arrivals of the central development section (characterised by flowing piano octaves and a deliciously exotic G minor statement of the opening theme), the vital return to the opening theme in the home key, and the tumultuous preparation for the solo cadenza. Normally in a concerto of this date, the soloist would not play after the cadenza, leaving it to the orchestra to wrap up the first movement; Beethoven, taking his lead again from Mozart, brings it back to be the prompter of an atmospheric coda.

Second Movement

The second, slow movement contains what is perhaps the most dramatically effective moment in the whole concerto, and it comes in the very opening piano chord. Beethoven was always an adventurous explorer of key relationships, but to pitch this meditative Largo in E major, thereby instantly sending the music into a distant and rarefied realm, is a coup de théâtre which would touch anybody. The music itself has a summer-afternoon drowsiness and warmth, its loving nature epitomised by the central section’s piano arpeggios, caressingly accompanying a drawn-out dialogue between flute and bassoon.

Final Movement

The work ends with a Rondo, gleefully returning us to C minor, though not without a few diversions, including an episode resembling a Mozart wind serenade, a short fugue, and another neck-tingling key-shift typical of Beethoven, as the main theme briefly re-acquaints us with the world of E major. Finally, with the end in sight and the listener thinking there can be no more surprises, a grand piano flourish heralds a switch to C major, and a cheeky altered-rhythm version of the theme to finish.

Note by Lindsay Kemp

Click 'Beethoven in Profile' in the navigation menu to see the composer profile.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No 1

✒️ 1795, rev 1800 | ⏰ 38 minutes

1 Allegro con brio

2 Largo

3 Rondo: Allegro scherzando

When Beethoven arrived in Vienna in 1792, just a few weeks before his 22nd birthday, it was to study with the world’s most famous composer, Joseph Haydn, and to absorb some of the atmosphere of what was arguably the musical capital of the world. He first made his name as a virtuoso pianist, performing in the private houses of the aristocracy, mostly in the form of improvisations so daring that one fellow pianist conceded that he was ‘no man, he’s a devil; he’ll play me and all of us to death’. There are accounts of him moving listeners to tears one moment, and the next berating them for not being sufficiently attentive.

When it came to formal composition, Beethoven was more circumspect. During the early 1790s he published few works, and those reluctantly. In 1794 a letter to the publisher Simrock revealed why: ‘I had no desire to publish any variations at present, for I wanted to wait until some more important works of mine, which are due to appear very soon, had been given to the world.’ In other words, he was deliberately holding back in order to make a splash with a batch of striking new compositions. This he duly did in 1795–96 with his Op 1 Piano Trios, Op 2 Piano Sonatas and Op 3 String Trio.

On 29 March 1795 Beethoven appeared for the first time in public in a work of his own, a piano concerto performed at the Burgtheater which was received with unanimous applause. We do not know which concerto this was – it could have been the one now known as No 2, which had actually been written some time before – but since it was advertised as ‘entirely new’ and Beethoven himself described No 2 as ‘not among my best compositions’, No 1 looks more likely to have been part of the grander strategy.

Despite his studies with Haydn, it is to Mozart that Beethoven owes the greatest debt in this piano concerto, and Mozart had provided the genre with its formal and expressive model during the 1780s. Yet while the First Piano Concerto has often been likened to Mozart in the context of Beethoven’s other works, there are plenty of ways it shows its author’s hand. This is a piece with the brightness and confidence of youth, one which takes as its starting point the congenially militaristic trumpet-and-drum world of Mozart’s concertos in the same key, and with brash dynamism and exuberantly robust piano writing admits the air of a new and more assertive age.

First Movement

The first movement begins quietly but soon gets into a vigorous stride, so that by the time the piano enters the best way for it to make an impression is by momentarily occupying itself with a totally new theme. A formal nicety occurs in the opening orchestral section, when the strings’ lovingly shaped second theme is three times curtailed, allowing the woodwind to cloud the music and lead it away to a new key. This is typical Beethoven, surprising or even shocking his audiences, but how much more pleasing the effect then becomes when this same theme later reappears in the woodwind, this time in its full, untroubled form.

Second and Final Movements

The central Largo is broadly expressive with warmth and a sense of well-being that comes as much from its harmonies and resourcefully varied textures (there is a telling role for solo clarinet) as from its melodic distinction. The concerto ends with a sparkling, spirited Rondo.

Note by Lindsay Kemp

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No 2

✒️ 1788, rev 1801 | ⏰ 30 minutes

1 Allegro con brio

2 Adagio

3 Rondo: Molto allegro

The orchestra for Piano Concerto No 2 is smaller than in Beethoven’s other concertos. There are no clarinets, trumpets or drums here, but Beethoven quickly shows that he can create a cheerily martial atmosphere without them.

First Movement

The fanfare figures of the opening bars pop up throughout the first movement, providing much of its flavour as well as a driving developmental force. As does the winding violin phrase which answers the fanfare’s first statement – this is the movement’s second important theme, split between the violins and arriving after an unexpected key-shift to D-flat major. Beethoven must have liked the effect of that key-shift: a short while after the piano has come in he makes another jump into D-flat when a veiled new theme for the piano emerges at the end of a long trill; and during the central development section he repeats the initial side-step with the same music, but in different keys.

Second Movement

The Adagio is broad and serene, and like many of Beethoven’s early slow movements is encrusted with elaborate piano figuration. There is a broodingly emotional quality to it too, however, and the climax of the movement comes in a brief, drooping recitative-like passage for the soloist, marked to be played ‘con gran espressione’ (with great expression).

Final Movement

The finale, as in all of Beethoven’s concertos, is a Rondo, here with four statements of the main theme separated by contrasting episodes. The movement’s character is established by the playful rhythmic catch of the main theme (notice how this appears slightly changed towards the end), and there are some knowing hints at the fashionable, percussive ‘Turkish’ style along the way. Mozart may have been his model, but the spirit here is pure young Beethoven.

Note by Lindsay Kemp

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No 4

✒️ 1804–06 | ⏰ 33 minutes

1 Allegro moderato

2 Andante con moto

3 Rondo: Vivace

The Fourth Piano Concerto was composed during a particularly rich phase in Beethoven’s life. Begun in 1804, it was completed two years later and thus dates from the same time as the Fifth Symphony, the Violin Concerto, and the original version of the opera Fidelio. It was premiered, with the composer as soloist, in a concert which also included the first performances of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, parts of the Mass in C major, and the Choral Fantasy.

Beethoven often worked on more than one composition at a time, so it is interesting to see the first movements of both the Fourth Piano Concerto and the Fifth Symphony dominated by the same four-note rhythm (short–short–short–long). However no one would claim that the two works are similar in personality; the broad lyrical cast of the piano concerto is in marked contrast to the Symphony’s terse, almost violent concentration. This relaxed demeanour was a new facet of Beethoven’s style, signifying his so-called ‘middle period’, and in its way it is no less typical or radical than his more familiar stormy side. The Fourth Piano Concerto, a work of surpassing beauty and poetry, is one of its most sublime examples.

First Movement

Without doubt the boldest stroke in the whole concerto is also one of the utmost gentleness. Normally at this time, a concerto would begin with a long passage for the orchestra, who would introduce the movement’s main themes before the soloist joins in later. Beethoven followed this etiquette in his first three piano concertos, but in the Fourth it is the piano which begins the piece on its own, with a touchingly quiet and simple chordal theme. For any audience expecting a grand extrovert opening, it is a heart stopping moment, though the orchestra subsequently takes over and presents the remaining themes in the normal way. Several new themes are heard, but that first piano theme (and its rhythm) continue to haunt the music. At those places where the music seems to become agitated, the tension is soon diffused; not even the loud, climactic return of the main theme, in massive chords batted between the pianist’s hands, can maintain its bombast for long.

Second Movement

The second movement is another departure from convention, discarding the usual formal models in favour of a dramatic interlude of operatic directness and power. There is a kind of confrontation occurring here between the stern unison denouncements of the orchestral strings and the sweetly harmonised responses of the piano, gradually winning the orchestra over until it falls into line with an acquiescent pizzicato (plucked strings) chord. Having won the argument, the piano draws itself to full height in a brief but disquieting show of strength before the movement comes to a close.

Final Movement

Beethoven now makes another radical gesture, moving stealthily and smoothly into the finale without a break. As in all his concertos, it is a Rondo, its returning theme being a tidy, fanfare-like tune which prompts the introduction for the first time in this concerto of trumpets and drums. After the high concentration of the slow movement, the mood here is expansive again. The piano’s suavely soaring second theme is subjected to elaborate contrapuntal treatment from the orchestra. The main theme appears in a ravishing smoothed-over version for the violas, and there is space for a spot of cat-and-mouse between the cadenza and the accelerated, headlong finish.

Note by Lindsay Kemp

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No 5, ‘Emperor’

✒️ 1809–11 | ⏰ 41 minutes

1 Allegro

2 Adagio un poco mosso

3 Rondo: Allegro

One has to wonder whether the organisers of the concert at which Beethoven’s Fifth Piano Concerto received its Viennese premiere in February 1812 – the actual premiere having taken place in Leipzig the previous November – provided the ideal audience. A contemporary report of the combined concert and art exhibition mounted by the Society of Noble Ladies for Charity tells us that ‘the pictures offer a glorious treat; a new pianoforte concerto by Beethoven failed’. And it is true that, while it was later to become as familiar a piano concerto as any, in its early years the ‘Emperor’ struggled for popularity. Perhaps its leonine strength and symphonic sweep were simply too much for everyone, not just the Noble Ladies.

Cast in the same key as Beethoven's ‘heroic’ Symphony No 3, it breathes much the same majestically confident air, though in a manner one could describe as more macho. Composed in the first few months of 1809, with war brewing between Austria and France, this is Beethoven in what must have seemed an overbearingly optimistic mood.

First Movement

The concerto is certainly not reticent about declaring itself. The first movement opens with extravagant flourishes from the piano punctuated with stoic orchestral chords, leading us with an unerring sense of direction towards the sturdy first theme. This march-like tune presents two important thematic reference-points in the shape of a melodic turn and a tiny figure of just two notes (a long and a short), which Beethoven refers to constantly in the course of the movement. The latter ushers in the chromatic scale with which the piano re-enters, and the same sequence of events later serves to introduce the development section.

Here the turn dominates, dreamily passed around the woodwind, but the two-note figure emerges ever more strongly, eventually firing off a stormy tirade of piano octaves. The air quickly clears, however, and reappearances of the turn lead back to a recapitulation of the opening material. Towards the end of the movement Beethoven makes his most radical formal move. In the early 19th century it was still customary at this point in a concerto for the soloist to improvise a solo passage (or cadenza). Beethoven did this in his first four concertos, but in the Fifth, for the first time, he includes one that is not only fully written out, but involves the orchestra as well. It was a trend that many subsequent composers, glad of the extra control, would follow.

Second and Final Movements

The second and third movements together take less time to play than the first. The Adagio, in the key of B major, opens with a serene, hymn-like tune from the strings, which the piano answers with a theme of its own before taking up the opening one in ornamented form. This in turn leads to an orchestral reprise of the same theme, now with greater participation from the winds and with piano decoration. At the end the music dissolves, then eerily drops down a semitone as the piano toys idly with some quiet, thickly scored chords. In a flash, these are then transformed and revealed to be the main theme of the bouncy Rondo finale, which follows without a break. Physical joins between movements were a trend in Beethoven’s music at this time, but so too were thematic ones.

At one point in this finale, with the main theme firmly established, the strings gently put forward the ‘experimental’ version from the end of the slow movement, as if mocking the piano’s earlier tentativeness. The movement approaches its close, however, with piano and timpani in stealthy cahoots before, with a final flurry, the end is upon us.

The 'Emperor'

The concerto’s nickname was not chosen by Beethoven, and, given the composer’s angry reaction to Napoleon’s self-appointment as Emperor in 1804, it may seem more than usually inappropriate. Yet there is an appositeness to it if we take the music’s grandly heroic stance as a picture of what, perhaps, an emperor ought to be. Beethoven once remarked that if he had understood the arts of war as well as he had those of music, he could have defeated Napoleon. Who, listening to this concerto, could doubt that?

Note by Lindsay Kemp

Ludwig van Beethoven

1770 (Germany) – 1827 (Austria)

Beethoven showed early musical promise, yet reacted against his father's attempts to train him as a child prodigy. The boy pianist attracted the support of the Prince-Archbishop, who supported his studies with leading musicians at the Bonn court. By the early 1780s, Beethoven had completed his first compositions, all of which were for keyboard. With the decline of his alcoholic father, Ludwig became the family breadwinner as a musician at court. Encouraged by his employer, the Prince-Archbishop Maximilian Franz, Beethoven travelled to Vienna to study with Joseph Haydn. The younger composer fell out with his renowned mentor when the latter discovered he was secretly taking lessons from several other teachers. Although Maximilian Franz withdrew payments for Beethoven's Viennese education, the talented musician had already attracted support from some of the city's wealthiest arts patrons.

His public performances in 1795 were well received, and he shrewdly negotiated a contract with Artaria & Co, the largest music publisher in Vienna. He was soon able to devote his time to composition or the performance of his own works. In 1800 Beethoven began to complain bitterly of deafness, but despite suffering the distress and pain of tinnitus, chronic stomach ailments, liver problems and an embittered legal case for the guardianship of his nephew, Beethoven created a series of remarkable new works, including the Missa solemnis and his late symphonies and piano sonatas. It is thought that around 10,000 people followed his funeral procession on 29 March 1827. Certainly, his posthumous reputation developed to influence successive generations of composers and other artists inspired by the heroic aspects of Beethoven's character and the profound humanity of his music.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Listen to Beethoven on LSO Live

Including the complete symphonies with Bernard Haitink, Fidelio and the Mass in C with Sir Colin Davis, and the recently released Christ on the Mount of Olives with Sir Simon Rattle.

Artist Biographies

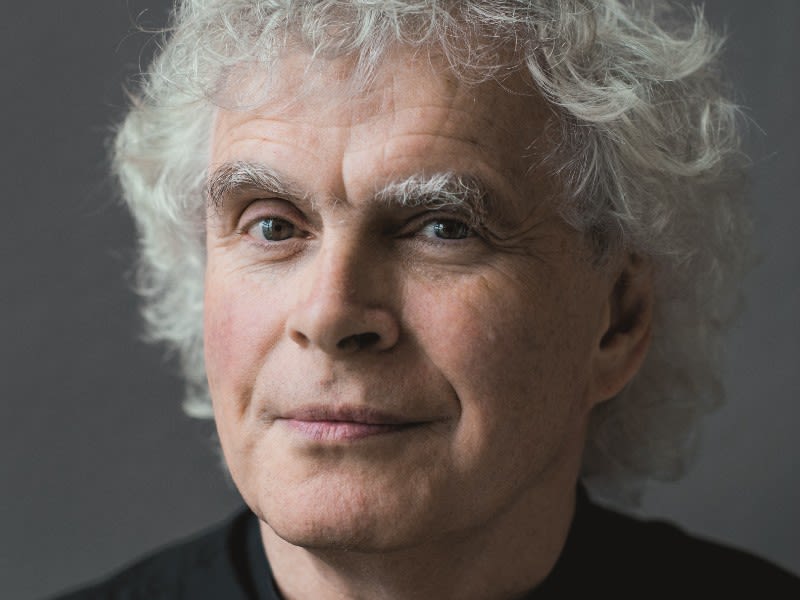

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

Sir Simon Rattle was born in Liverpool and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1980 to 1998, he was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. He moved to Berlin in 2002 and held the positions of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic until he stepped down in 2018. Sir Simon became Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and spent the 2017/18 season at the helm of both ensembles.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI record label (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance) Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortileges, Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives, Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

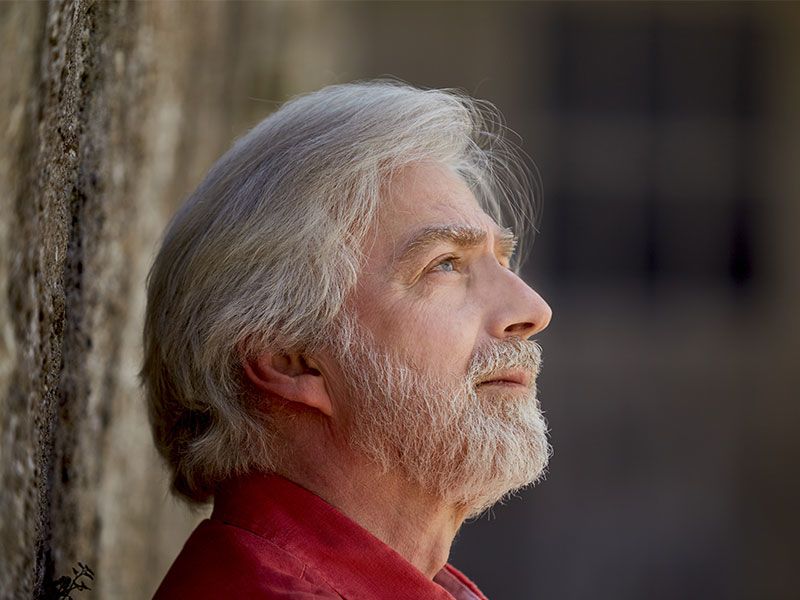

Krystian Zimerman

piano

Krystian Zimerman came to fame when he was awarded First Prize in the Chopin Competition at the age of 18. He has since enjoyed a world-class career working with the world’s most prestigious orchestras and giving a select number of recitals in the top international concert halls.

He has collaborated with many pre-eminent musicians – chamber partners such as Gidon Kremer, Kyung-Wha Chung and Yehudi Menuhin, and conductors such as Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan, Pierre Boulez, Zubin Mehta, Bernard Haitink and Sir Simon Rattle.

As part of the Chopin 200 celebrations in 2010, Zimerman gave the Chopin Birthday recital in London’s International Piano Series on the anniversary of the composer’s birth. In 2013, to mark the centenary of Lutosławski’s birth, Zimerman performed the Piano Concerto – which the composer wrote for him – in a number of cities worldwide. In recent seasons he made his debut in China with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra under Paavo Järvi and gave concerts with the Taipei and Bangkok symphony orchestras. He continued his collaboration with Rattle and the LSO in 2017/18 with performances of The Age of Anxiety in connection with the Bernstein anniversary celebrations. During 2020 Zimerman performed all of the Beethoven piano concertos, in various European cities, for the 250th anniversary.

Zimerman has developed his own individual approach to recording, a process which he controls at each stage. During his long collaboration with Deutsche Grammophon his recordings have earned him many top awards. He transports his own piano for every recital and many concerto performances, a practice which has made audiences more aware of the complexities and capabilities of the instrument. Performing on his own familiar instrument, combined with his piano-building expertise, helps him minimise any distractions from purely musical issues.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Piano Concertos Nos 3 & 1

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Carmine Lauri

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Elizabeth Pigram

Claire Parfitt

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Second Violins

David Alberman

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Alix Lagasse

Csilla Pogany

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

Julia O’Riordan

Robert Turner

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Alastair Blayden

Jennifer Brown

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Double Basses

Colin Paris

Patrick Laurence

Thomas Goodman

José Moreira

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Rosie Jenkins

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bassoons

Daniel Jemison

Rachel Gough

Shelly Organ

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Trumpets

David Elton

Niall Keatley

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

On Stage

Piano Concertos Nos 2 & 4

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Carmine Lauri

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Elizabeth Pigram

Claire Parfitt

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Csilla Pogany

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

German Clavijo

Julia O'Riordan

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Alastair Blayden

Jennifer Brown

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Double Basses

Colin Paris

Patrick Laurence

Thomas Goodman

Joe Melvin

José Moreira

Flute

Gareth Davies

Oboes

Olivier Stankiewicz

Rosie Jenkins

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bassoons

Daniel Jemison

Shelly Organ

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Alexander Edmundson

Trumpets

David Elton

Niall Keatley

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

On Stage

Piano Concerto No 5, 'Emperor'

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Carmine Lauri

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Claire Parfitt

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Thomas Norris

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Csilla Pogany

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

German Clavijo

Stephen Doman

Carol Ella

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Alastair Blayden

Jennifer Brown

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Hilary Jones

Amanda Truelove

Double Basses

Colin Paris

Patrick Laurence

Matthew Gibson

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Rosie Jenkins

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Shelly Organ

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Trumpets

David Elton

Niall Keatley

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Meet the Members of the LSO on our website

Thank You for Watching