London Symphony Orchestra Spring 2021

Berg & Schubert

Music from the heart: Sir Simon Rattle and Leonidas Kavakos swing from profound sorrow to boundless joy, with Viennese classics by Schubert and Berg.

Berg & Schubert

Alban Berg Violin Concerto

Franz Schubert Symphony No 9, 'The Great'

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

Leonidas Kavakos violin

London Symphony Orchestra

This performance is supported by the National Bank of Greece to celebrate the 200th Anniversary of Greek Independence, within the context of the 'Bicentennial Initiative 1821–2021', in which leading Greek foundations are taking part.

This performance is broadcast on Marquee TV. Available to watch for free for seven days from 21 January 2021, then on demand with a subscription.

Recorded at LSO St Luke's on Thursday 7 January 2021 in COVID-19 secure conditions.

Welcome and Thank You for Watching

Whilst we are unable to come together with audiences at our Barbican home, we are pleased to continue releasing a programme of online content and streamed broadcasts, making music available for everyone to enjoy digitally in the coming weeks. A warm welcome to the numerous conductors and soloists joining us, among them many firm friends and regular collaborators with the Orchestra. We are delighted also to welcome back members of our family of conductors.

It is a pleasure to invite you to watch and listen today online, and we extend thanks to our broadcast partner Marquee TV for streaming this concert. I hope you enjoy the performance, and look forward to welcoming you back in person when we are able to re-open our doors.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra, allow us to perform together again on stage and to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO’s return to work is supported by Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne and DnaNudge.

This performance is generously supported by our Technical Partner, Yamaha Professional Audio.

Share Your Thoughts

We always want you to have a great experience, however you watch the LSO. Please do take a few moments at the end to let us know what you thought of the streamed concert and digital programme. Just click Share Your Thoughts in the navigation menu.

Alban Berg

Violin Concerto

✒️1936 | ⏰26'

1 Andante – Allegretto

2 Allegro – Adagio

Leonidas Kavakos violin

In February 1935, Berg was visited in Vienna by a man with a mission: Louis Krasner, a violinist born in Ukraine and raised in the US, was determined to get a concerto out of the composer. Berg, at a time when his music’s prospects in Germany looked dubious, might well have warmed to this invitation from across the Atlantic. In any event, he put his opera Lulu on hold and turned to Krasner’s concerto.

Quite soon, in April 1935, there was a sad loss within Berg’s circle: the 18-year-old Manon Gropius. Manon was the daughter of composer Gustav Mahler's widow, Alma, and her second husband, Walter Gropius, architect and founder of the Bauhaus school. Berg decided to memorialise Manon in his concerto. This luminous being and 'angelic gazelle' who 'radiated timidity even more than beauty' would be at once described and enacted by the violin, in a work to be subtitled: ‘To the memory of an angel’.

More than one angel, however, sings wordlessly in Berg’s music. Telling the story of Alma’s daughter, Berg remembered his own child, born of his teenage liaison with a kitchen maid at his family’s summer place in Carinthia. At the same time, the concerto draws electricity from his passionate involvement with the sister of Alma Mahler’s third husband (the writer Franz Werfel): Hanna Fuchs-Robettin as she then was, married to a businessman and living in Prague. Her initials and the composer’s are musically woven into the score, as are numbers Berg associated with each of them. The calamity that overtakes the concerto is partly that of the death of an angelic adolescent, partly that of an impossible love.

For paradoxes of grief and adoration, Berg found a perfect language in composer Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique. Prompted by harp and clarinets, the entry of the soloist in the first movement embraces the tuning of the four strings of the violin. Soon the soloist plays the twelve-note row, rising and falling; similar ascents and descents recur through the work. As the tuning idea returns, the music prepares a smooth transition into the second part of this first movement, a Ländler, or country waltz, which turns to a Carinthian folk song. After a hectic period of looking back on itself, the movement arrives at a point of rest.

In Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, developed in the 1920s, all twelve notes of the chromatic scale must be played the same amount of times.

Popular in Austria and Bavaria at the end of

the 18th century, the Ländler is a folk dance featuring hopping and stamping.

Any peace is immediately broken by the start of the second movement – in two parts like the first, but with their difference in speed reversed and exaggerated. The first part, fast, is marked ‘free, like a cadenza’, and its outer sections are violent, post-catastrophic, held with increasing firmness to a menacing rhythmic gesture. Once the storm has passed, the violin is discovered leading the way into the finale with a chorale tune: ‘Es ist genug’ (‘It is enough’), quoted from a setting by Johann Sebastian Bach.

Less than four months after Manon’s death, the concerto was finished. By the end of the year, Berg himself had passed away.

Note by Paul Griffiths

Alban Berg

1885–1935 (Austria)

Although piano lessons formed part of Berg’s general education, the boy showed few signs of exceptional talent for music. He struggled to pass his final exams at the Vienna Gymnasium, preferring to learn directly about new trends in art, literature, music and architecture from friends such as Oskar Kokoschka, Gustav Klimt and Adolf Loos.

On graduating from school, Berg accepted a post as a local government official, but in October 1904 was inspired by a newspaper advertisement to study composition with Arnold Schoenberg. He studied for six years with Schoenberg, who remained his close friend and mentor. During this time Schoenberg evolved a new approach to composing, gradually moving away from the norms of tonal harmony.

In 1910, Berg completed his String Quartet Op 3, in which he revealed an independent creative flair. Berg’s self-confidence grew with the composition of several miniature works and, in 1914, the large-scale Three Pieces for Orchestra. Service with the Austrian Imperial Army during World War I did not completely halt Berg’s output; indeed, he began his first opera, Wozzeck, in the summer of 1917. The work was premiered at the Staatsoper Berlin in December 1925 and, despite hostile early criticism, has since entered the international repertoire.

As an innovative composer, Berg successfully married atonality – and, later, a harmonic and melodic language based on the use of all twelve tones of the chromatic scale – with forms from the past. Traces of popular music also surface in his works, notably so in his opera Lulu (1929–35), a powerful tale of immorality, completed from the composer’s sketches only after the death of his widow in 1976. Berg himself died in 1935 of septicaemia, almost certainly caused by complications following an insect bite.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Franz Schubert

Symphony No 9 in C major D944, 'The Great'

✒️1825, revised 1826 | ⏰ 47'

1 Andante – Allegro ma non troppo

2 Andante con moto

3 Scherzo: Allegro vivace

4 Finale: Allegro vivace

It is not clear when people first began referring to Schubert’s last completed symphony as the ‘Great C major’. Apparently the tag was first applied to differentiate it from the ‘little’ C major symphony, known as ‘No 6’, which Schubert wrote in 1817–18. But the nickname is well deserved: not only is it conceived on a huge scale, its sophistication and formal mastery are as impressive as its vitality, imaginative range and the infectious memorability of its main themes.

That mastery is all the more impressive when one considers that it was only the year before he began work on the score that Schubert had declared his intention in a letter ‘to pave my way to grand symphony’. That same year, 1824, Schubert had also heard the premiere of Beethoven’s own 'Choral’ Ninth Symphony – a big influence to digest, one might have thought, and yet Schubert’s response to that challenge is confident and utterly original. Indeed Schubert clearly felt so sure of himself that he was able to invoke Beethoven’s Ninth without fear of comparison: woodwind figures in Schubert’s finale contain an unmistakable reference to a phrase from Beethoven’s famous ‘Ode to Joy’ theme.

Almost certainly the symphony’s vigour and assurance reflect something of Schubert’s mood in the summer of 1825, when he made a long walking tour with friends in Upper Austria. At one point in that extended holiday the party stayed at the house of Anton Ottenwalt, brother-in-law of Schubert’s close friend Josef von Spaun. Ottenwalt wrote that ‘Schubert looks so well and strong, is so bright and relaxed, so genial and communicative, that one cannot but be sincerely delighted’. In the next sentence, Ottenwalt reports that Schubert ‘had been working on a symphony … which is to be performed in Vienna this winter’. For Ottenwalt there was clearly a connection between Schubert’s state of mind and his current musical fertility.

But one could go further than that. The symphony is dominated by images of physical movement: the muscular, striding theme of the first movement; the exuberant waltz-tunes of the Scherzo; the hurtling vitality of the Finale – even the ‘slow’ second movement is carried forward by a march-like tread, introduced on the strings before the oboe sounds the leading melody. It is hard to imagine a greater contrast with the lyrical, introverted character of Schubert's previous symphony of three years earlier, the B minor ‘Unfinished’ Symphony, composed in much less happy times. But an invigorating walking regime, a delight in nature and thoughts of God inspired by sublime landscapes in the summer of 1825 – all of this is implicit in the ‘Great’ C major Symphony.

Despite his excellent spirits and abundant inspiration, Schubert had to wrestle with the symphony before it arrived at its final form. The score was extensively revised in 1826, as a result of which it became even longer than that already ambitious first version. Finally the symphony was handed over to the Vienna Philharmonic Society; parts were duly copied, and at some time towards the end of 1826 there was a run-through by the orchestra. But the hoped-for public performance did not materialise. According to one account, the symphony was ‘provisionally put aside, because of its length and difficulty’. Schubert was never to hear the work performed in concert. It wasn’t until March 1839 – eleven years after the composer’s death – that Mendelssohn conducted it at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. And despite enthusiastic championship, it was not widely recognised as the masterpiece it is until much later.

Extract from notes by Stephen Johnson

Franz Schubert

1797–1828 (Austria)

In childhood, Schubert was taught violin by his schoolmaster father and piano by his eldest brother. He rapidly became more proficient than his teachers, and showed considerable musical talent, so much so that in 1808 he became a member of Vienna’s famous Imperial Court chapel choir. He was educated at the Imperial City College, where he received lessons from the composer Antonio Salieri. His father, eager that Franz should qualify as a teacher and work in the family’s schoolhouse, encouraged the boy to return home in 1814. Compositions soon began to flow, although teaching duties interrupted progress. Despite his daily classroom routine, Schubert managed to compose 145 songs in 1815, together with four stage works, two symphonies, two Masses and a large number of chamber pieces.

Though the quantity of Schubert’s output is astonishing enough, it is the quality of his melodic invention and the richness of his harmonic conception that are the most remarkable features of his work. He was able to convey dramatic images and deal with powerful emotions, as he so often did in his songs and smaller chamber works. The public failure of his stage works and the reactionary attitudes to his music of conservative Viennese critics did not restrict his creativity, nor his enjoyment of composition; illness, however, did affect his work and outlook. In 1824 Schubert was admitted to Vienna’s General Hospital for treatment for syphilis. Although his condition improved, he suffered side-effects from his medication, including severe depression. During the final four years of his life, Schubert’s health declined; meanwhile, he created some of his finest compositions, chief among which are the song-cycles Winterreise and Schwanengesang, and the last piano sonatas.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Artist Biographies

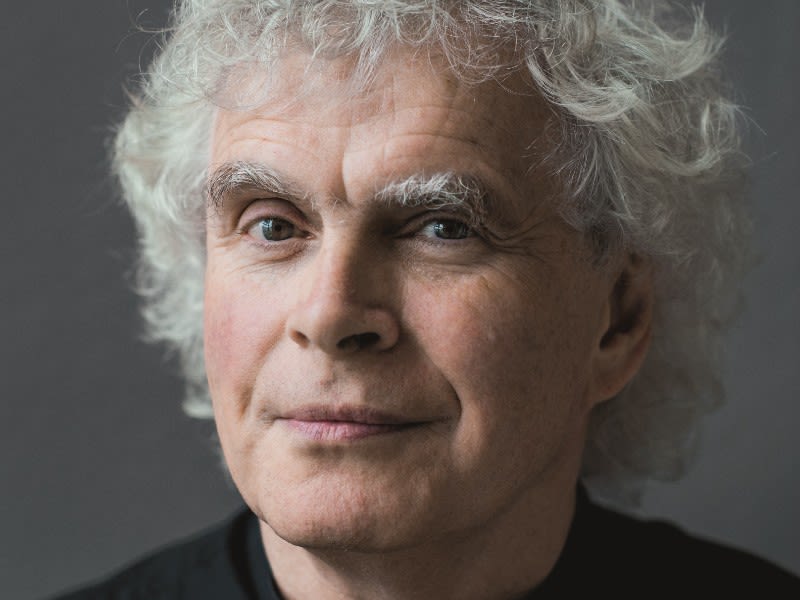

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

Sir Simon Rattle was born in Liverpool and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1980 to 1998, he was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. He moved to Berlin in 2002 and held the positions of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic until he stepped down in 2018. Sir Simon became Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and spent the 2017/18 season at the helm of both ensembles.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI record label (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance) Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortileges, Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives, Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

Leonidas Kavakos

violin

Leonidas Kavakos is recognised across the world as a violinist and artist of rare quality. The three important mentors in his life have been Stelios Kafantaris, Josef Gingold and Ferenc Rados, with whom he still works. By the age of 21, Leonidas Kavakos had already won three major competitions: the Sibelius Competition in 1985, and the Paganini and Naumburg competitions in 1988. This success led to him recording the original Sibelius Violin Concerto (1903–04), the first recording of this work in history, and which won Gramophone Concerto of the Year Award in 1991.

In 2007, for his recording of the complete Beethoven Sonatas with Enrico Pace, Kavakos was named Echo Klassik Instrumentalist of the year. In 2014, Kavakos was awarded Gramophone Artist of the Year. Further accolades came in 2017 when Kavakos was awarded the prestigious Leonie Sonning Prize – Denmark’s highest musical honour, given annually to an internationally recognised composer, conductor, instrumentalist or singer.

In recent years, Kavakos has succeeded in building a strong profile as a conductor and has conducted the LSO, New York Philharmonic, Houston Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Gürzenich Orchester, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Vienna Symphony, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Filarmonica Teatro La Fenice and the Danish National Symphony Orchestra.

Born and brought up in a musical family in Athens, Kavakos curates an annual violin and chamber music masterclass in Athens, which attracts violinists and ensembles from all over the world and reflects his deep commitment to the handing on of musical knowledge and traditions. Part of this tradition is the art of violin and bow-making, which Kavakos regards as a great mystery and to this day, an undisclosed secret. He plays the 'Willemotte' Stradivarius violin of 1734 and owns modern violins made by F Leonhard, S P Greiner, E Haahti and D Bagué.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Leader

Carmine Lauri

First Violins

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Csilla Pogany

Second Violins

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

Naoko Keatley

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

Germán Clavijo

Stephen Doman

Robert Turner

Sofia Silva Sousa

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Jennifer Brown

Noel Bradshaw

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Laure Le Dantec

Amanda Truelove

Double Basses

Sam Loeck

Patrick Laurence

Matthew Gibson

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Flute

Gareth Davies

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Rosie Jenkins

Maxwell Spiers

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bass Clarinet

Katy Ayling

Saxophone

Simon Haram

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Dominic Tyler

Contra Bassoon

Dominic Morgan

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Alexander Edmundson

Flora Bain

Trumpets

James Fountain

Niall Keatley

Trombones

Peter Moore

Tom Berry

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Harp

Bryn Lewis

Meet the Members of the LSO on our website

Thank You for Watching