London Symphony Orchestra

Britten, Fauré & Dvořák

Welcome

After 14 months away, it is wonderful to be able to welcome our audiences back to the LSO’s home at the Barbican. The last year has brought challenges and moments of sadness for all, yet we also know that music has a great power to heal, comfort and create connections, even in the most difficult of times. It has been heartening for everyone in the LSO to know that the performances we have shared digitally during the pandemic have been enjoyed by so many, and we are thrilled that you are able to join us in person today.

For our first public concerts of 2021, we are joined by LSO Music Director Sir Simon Rattle for what promise to be uplifting performances of music, featuring works by Britten, Fauré and Dvořák, in the presence this evening of the Right Honourable the Lord Mayor of the City of London, William Russell, and the Lady Mayoress. We look forward in the coming month to being joined by other members of our family of conductors who have been sorely missed over the past year: our Conductor Laureate Michael Tilson Thomas, and Principal Guest Conductor François-Xavier Roth.

The LSO has been sustained through this most challenging of times through the generosity of its supporters, and we extend our gratitude to all those who have helped us to continue sharing our music with the widest possible audience. Sincere thanks to the City of London Corporation and the Arts Council, who maintained our grants through the whole period, and our loyal Patrons, Friends, trusts, foundations and corporate supporters, in particular DnaNudge, whose regular testing of the Orchestra has allowed us to return safely to work. You have enabled us to continue sharing music online, through LSO Discovery, our learning and community programme, and with regular streamed concerts from LSO St Luke’s. We are also grateful to the government and the Arts Council for the support of the Culture Recovery Fund, and for a continued openness to work together to solve problems, which has allowed music-making to continue in this difficult time.

In the autumn of 2020 we launched our Always Playing Appeal to assist our recovery from the pandemic, with a lead gift from Alex and Elena Gerko. We are extremely grateful for the generous donations we have received since, and continue to receive, all of which are key to securing the future of the LSO.

Final thanks to all of you, our audience members, for watching our online concerts, buying tickets, and for staying connected to us on social media. We have been bolstered by your messages of support, and as we take these next steps to recovery it is a pleasure to be sharing in live music-making together once again. I hope that you enjoy today’s concert, and I look forward to welcoming you back to many more in the months ahead.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Using these Notes

You can use your phone to view these notes during the concert. Use the menu icon (three horizontal lines) in the top right of the screen to navigate.

Free WiFi is available in the Concert Hall, just connect to 'Barbican Free Wifi'.

Please Note

Phones should be switched to silent mode. We ask that you use your phone only for reading the notes during the music. Photography and audio/video recording are not permitted during the performance.

Print at Home

A reduced version of this programme is available to download and print at home.

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra and enable us to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

Benjamin Britten

The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra

✒️1945 | ⏰17 minutes

Benjamin Britten’s celebrated work for children was commissioned for a 1946 Ministry of Education film called Instruments of the Orchestra. It was completed at the end of an extraordinary year for the young composer, which had seen the premiere of his opera Peter Grimes, the song cycle The Holy Sonnets of John Donne, his second string quartet and his concert tour of the concentration camps with Yehudi Menuhin. Yet in this clever, playful work Britten was able to revive his childlike sense of discovery. He paid tribute, too, to his beloved predecessor, composer Henry Purcell, by taking his theme from a hornpipe rondeau from the incidental music to Abdelazar or The Moor’s Revenge. It is Britten's use of Purcell’s theme which gives the work its grounded, timeless quality. The poet Montagu Slater wrote a commentary for speaker to elucidate the music, but it is most often played today as a concert piece without narration, its notes speaking more eloquently than words.

After a tutti (meaning all together) statement of the opening theme, each section of the orchestra, including the percussion, steps forward into the limelight for a reprise before the work splinters into an ingenious series of variations over tremolo strings. From chirruping flutes prompted by harp, ardent oboes, jaunty tuba below acrobatic clarinets, tragic-comic bassoons, dazzling strings, tender violas (the composer’s own instrument) – even the double basses have their moment of glory with an impassioned melody in an outlandishly high register. The harp variation recalls Britten's scintillating Ceremony of Carols and prefaces a brooding episode for horns, which gives way to a typically virtuosic trumpet canon and lordly trombones echoed by tuba.

Britten, the composer of film and stage, revels in his ability to produce a string of brilliant miniatures, capturing a myriad range of styles, some deadly serious, some delightfully tongue-in-cheek, most inimitably his own. The final, apprehensive variation for percussion is particularly witty.

Now, when every instrumentalist has had a turn, piccolos begin a tearaway fugue, with winds and then strings joining it in rapid succession, harps followed by horns, trumpets and trombones. Then, as it rises to a terrific climax, there comes what David Hemmings (Britten’s first Miles in his opera The Turn of the Screw) has called ‘the champagne moment’, when the original stately theme glides gloriously in on lower brass, locking perfectly onto the racing fugue and driving through a heart-stopping finale.

Note by Helen Wallace

Benjamin Britten

1913–76 (United Kingdom)

Benjamin Britten received his first piano lessons from his mother, who encouraged her son's earliest efforts at composition. In 1924 he heard Frank Bridge's tone poem The Sea and began to study composition with him three years later. In 1930 he gained a scholarship to the Royal College of Music, where he studied composition with John Ireland and piano with Arthur Benjamin. Britten attracted wide attention when he conducted the premiere of his Simple Symphony in 1934. He worked for the GPO Film Unit and various theatre companies, collaborating with such writers as W H Auden and Christopher lsherwood. His lifelong relationship and working partnership with Peter Pears developed in the late 1930s. At the beginning of World War II, Britten and Pears remained in the US; on their return, they registered as conscientious objectors and were exempted from military service.

The first performance of the opera Peter Grimes in 1945 opened the way for a series of magnificent stage works mainly conceived for the English Opera Group. In June 1948 Britten founded the Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts, for which he subsequently wrote many new works. By the mid-1950s he was generally regarded as the leading British composer, helped by the international success of operas such as Albert Herring, Billy Budd and The Turn of the Screw. One of his greatest masterpieces, the War Requiem was first performed on 30 May 1962 for the festival of consecration of St Michael's Cathedral, Coventry, its anti-war message reflecting the composer's pacifist beliefs.

A remarkably prolific composer, Britten completed works in almost every genre and for a wide range of musical abilities, from those of school children and amateur singers to such artists as Mstislav Rostropovich, Julian Bream and Peter Pears.

Composer profile by Philip Reed

Gabriel Fauré

Pelléas et Mélisande – Suite

✒️1898 | ⏰ 13 minutes

1 Prélude: quasi adagio

2 La Fileuse: andantino quasi allegretto

4 La mort de Mélisande: molto adagio

Maurice Maeterlinck’s tragic play, Pelléas et Mélisande, has inspired a number of major musical works, not least Schoenberg’s tone poem, Sibelius’ incidental music and, perhaps best known of all, Debussy’s opera.

But Fauré’s music for an early London production of the play preceded them all and, despite being second choice behind a busy Debussy, the actress/producer Mrs Patrick Campbell ‘felt sure Gabriel Fauré was the composer needed.’ He was up against it, in the great tradition of incidental music, and called on his pupil Charles Koechlin to help orchestrate his piano score quickly for the premiere at the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1898. Campbell was delighted:

‘[Fauré] grasped with most tender inspiration the poetic purity that pervades and envelops Maeterlinck’s play.’

The play itself revolves around a doomed love triangle: Mélisande, lost and childlike; Golaud, who rescues and marries her; and his younger brother Pelléas, who falls in love with Mélisande. Golaud, discovering their affair, kills Pelléas and wounds Mélisande, who dies in childbirth.

The suite, re-orchestrated by the composer himself, begins with the Prelude to Act 1: Mélisande is lost and lonely in the forest and we hear Golaud’s hunting horn in the distance before he discovers Mélisande. The Prelude to Act 3 follows: Mélisande at the spinning wheel, the music capturing her innocence and charm. Tonight's performance moves straight onto the final piece, The Death of Mélisande, which was played at Fauré’s own funeral as his coffin was taken out of the church.

Gabriel Fauré

1845–1924 (France)

The youngest of six children, Gabriel Fauré became preoccupied with music at an early age. He improvised on the harmonium at the École normale graduate school run by his father in Montgauzy in Provence, and later recalled that ‘an old blind lady’ gave him elementary lessons. In 1853 a visiting civil servant heard the young boy play and advised Fauré‘s father to send his son to the recently established École Niedermeyer school in Paris, a centre for religious music and the revival of music from past times. Here Fauré studied organ, absorbed the musical language of plainsong and discovered Renaissance polyphony. After Niedermeyer’s death in 1861 Fauré studied piano with composer Camille Saint-Saëns, who also introduced his talented pupil to contemporary works by, among others, Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner.

Between 1861 and his death, Fauré wrote over 200 works, including a three-act opera, Pénèlope (considered by many as the composer’s masterpiece) and, in the final years of his life, a series of refined, emotionally charged songs, chamber and solo piano pieces that still sound remarkably fresh and original. For much of his career he earned his living as organist at a number of Parisian churches, by giving private piano and harmony lessons, and as choirmaster at the Madeleine. From 1905 until 1920, he served as director of the Paris Conservatoire, and enjoyed public recognition as a composer. Deafness and other serious ailments blighted his final years.

Claude Debussy spoke of his older contemporary as the ‘Master of Charms’, dismissing Fauré’s work as lightweight and branding him as the ‘music-case of a band of snobs’. In truth, the composer transformed the French mélodie into a richly expressive art form, developed a highly personal harmonic language while others were struggling to copy that of Wagner, and created a series of elegant, often sensual works.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Antonín Dvořák

Slavonic Dances Op 46

✒️1878 | ⏰ 38 minutes

No 1 in C major: Furiant

No 2 in E minor: Dumka

No 3 in A-flat major: Polka

No 4 in F major: Sousedská

No 5 in A major: Skočná

No 6 in D major: Sousedská

No 7 in C minor: Skočná

No 8 in G minor: Furiant

Antonín Dvořák was relatively unknown at the time of his Slavonic Dances commission in 1878. The German composer Johannes Brahms had spotted that Dvořák had won several prizes and suggested his publishers contact the younger Czech. They did, requesting he write Bohemian dances in the style of Johannes Brahms’ Hungarian Dances.

Opus 46 was first published as a set of piano duets for the amateur market. Their popularity spread like wildfire, and soon Dvořák orchestrated them and composed a second set in 1886. His seat in the musical firmament was confirmed. At the time of Dvořák’s birth, Czech people had no real country of their own. The regions where they lived – Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia – were part of the Austrian Empire, but it was during his lifetime that regions fought for political independence which filtered through to the arts community. Composers started wanting musical independence, too, overshadowed, as it had been, by German and Italian styles. They began using folk tunes and dance rhythms, the beginnings of musical nationalism.

Dvořák’s life-long passion was the Czech national folk tradition, and while he wrote a lot of Czech-sounding compositions, in fact, he hardly ever used any actual folk melodies in his music. He was a sort of magpie, stealing elements from his native musical heritage, most notably the rhythms, but writing the melodies himself. His Slavonic Dances are no different , but that does not belie their heritage.

The Dances

The set of dances literally flies off the score with an untamed Furiant, for which dancers – and the orchestra – have to be on their toes in more ways than one as it constantly shifts gears. A rocking, yearning Dumka follows, led by soft flutes, with a jaunty mid-section perhaps remembering happy times. The Polka has its roots in Czech culture, originated by peasants, but here the usual ‘quick-quick-slow’ rhythm is heard on occasional blasts, enveloped by a gentle melody. The more sedate Sousedská dance is the longest dance of the set before launching into the first Skočná: a galloping rhythm drives forward this ‘leaping couples’ dance. Trills and delicate steps characterise the second lilting Sousedská (No 6); listen out for a beautiful countermelody on the cellos. The second Skočná (No 7) in keeping with the style of dance has a cocky surety about itself. The finale, a second Furiant (No 8) to bookend the set, does not disappoint with its lurch from major to minor and a gorgeous lilting mid-section led by the oboe, hinted at again before the final definitive flourish.

Note by Sarah Breeden

Antonín Dvořák

1841–1904 (Bohemia, now Czech Republic)

Born into a peasant family, Antonín Dvořák developed a love of folk tunes at an early age. His father inherited the lease on a butcher’s shop in the small village of Nelahozeves, north of Prague. When he was 12, the boy left school and was apprenticed to become a butcher, at first working in his father’s shop and later in the town of Zlonice. Here Dvořák learned German and also refined his musical talents to such a level that his father agreed he should pursue a career as a musician.

In 1857 he enrolled at the Prague Organ School, during which time he became inspired by the music dramas of Richard Wagner: opera was to become a constant feature of Dvořák’s creative life. His first job was as a viola player, supplementing his income by teaching. In the mid-1860s he began to compose a series of large-scale works, including his Symphony No 1, ‘The Bells of Zlonice’ and the Cello Concerto. Two operas, a second symphony, many songs and chamber works followed before he decided to concentrate on composition.

In 1873 he married one of his pupils, and in 1874 received a much-needed cash grant from the Austrian government. Brahms lobbied the publisher Simrock to accept Dvořák’s work, leading to the publication of his Moravian Duets and a commission for a set of Slavonic Dances. The nationalist themes expressed in Dvořák’s music attracted considerable interest beyond Prague. In 1883 he was invited to London to conduct a concert of his works, and he returned to England often in the 1880s to oversee the premieres of several important commissions, including his Seventh Symphony and Requiem Mass. Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor received its world premiere in London in March 1896. His Ninth Symphony, ‘From the New World’, a product of Dvořák’s years in the US from 1892–95, confirmed his place among the finest of late 19th-century composers.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Artist Biographies

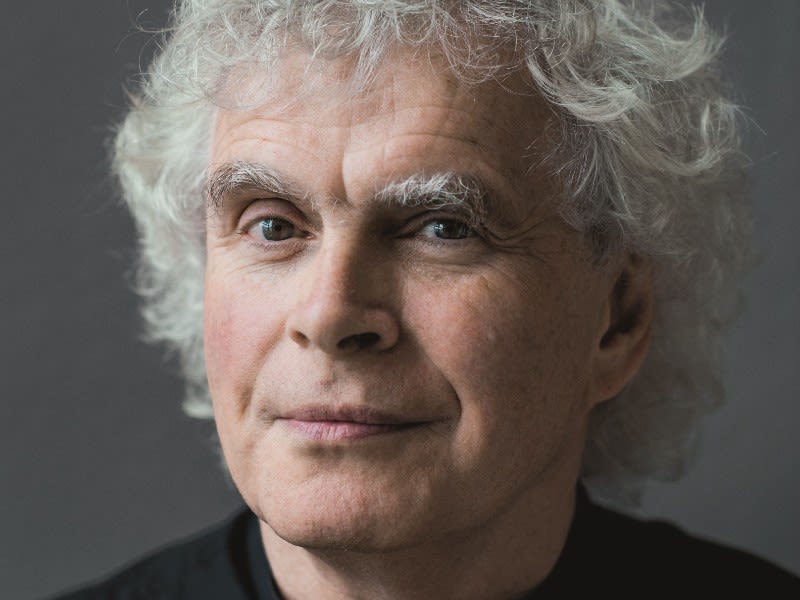

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

From 1980 to 1998, Sir Simon was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. In 2002 he took up the position of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, where he remained until the end of the 2017/18 season. Sir Simon took up the position of Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and will remain there until the 2023/24 season, when he will take the title of Conductor Emeritus. From the 2023/24 season Sir Simon will take up the position of Chief Conductor of the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks in Munich. He is a Principal Artist of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and Founding Patron of Birmingham Contemporary Music Group.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance), Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortilèges, Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker – Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Rachmaninoff's Symphony No 2, Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Leader

Carmine Lauri

First Violins

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Claire Parfitt

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Naoko Keatley

Second Violins

David Alberman

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Alix Lagasse

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Rachel Roberts

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

Germán Clavijo

Carol Ella

Robert Turner

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Jennifer Brown

Noël Bradshaw

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Amanda Truelove

Double Basses

David Stark

Colin Paris

Patrick Laurence

Matthew Gibson

José Moreira

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Patricia Moynihan

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Olivier Stankiewicz

Rosie Jenkins

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Shelly Organ

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Alexander Edmundson

Flora Bain

Trumpets

James Fountain

Niall Keatley

Trombones

Peter Moore

Richard Ward

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Tom Edwards

Jeremy Cornes

Oliver Yates

Harp

Bryn Lewis

Programme Contributors

Helen Wallace is Artistic & Executive Director at Kings Place, London; as well as a freelance writer and author. She has held the prestigious position as Editor of BBC Music Magazine in the past.

Philip Reed’s publications include The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten (two volumes, co-edited with Donald Mitchell) and contributions to studies of Peter Grimes and the War Requiem.

Andrew Stewart is a freelance music journalist and writer. He is the author of The LSO at 90, and contributes to a wide variety of specialist classical music publications.

Sarah Breeden contributes to BBC Proms family concert programmes, has written on film music for the LPO and LSO, school notes for the London Sinfonietta and the booklet notes for the EMI Classical Clubhouse series. She worked for the BBC Proms for several years.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO's return to work is generously supported by the Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne, DnaNudge and the Weston Culture Fund.