FTWeekend Digital Festival:

An Evening with the LSO

Dvořák & Tchaikovsky

Welcome and Thank You for Watching

Whilst we are unable to come together with audiences at our Barbican home, we are pleased to continue releasing a programme of online content and streamed broadcasts, making music available for everyone to enjoy digitally. A warm welcome to the numerous conductors and soloists joining us, among them many firm friends and regular collaborators with the Orchestra.

It is a pleasure to invite you to watch and listen today online to this live performance as part of the FTWeekend Digital Festival. I hope you enjoy the concert, and look forward to welcoming you back in person when we are able to re-open our doors.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Dvořák & Tchaikovsky

Antonín Dvořák Scherzo capriccioso

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Act Two from 'The Nutcracker'

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

This performance is broadcast as part of the FTWeekend Digital Festival, in partnership with Fortnum & Mason.

Recorded at LSO St Luke's on Thursday 18 March 2021 in COVID-19 secure conditions.

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra, allow us to perform together again on stage and to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO’s return to work is supported by DnaNudge.

Generously supported by the Weston Culture Fund.

Share Your Thoughts

We always want you to have a great experience, however you watch the LSO. Please do take a few moments at the end to let us know what you thought of the streamed concert and digital programme. Just click 'Share Your Thoughts' in the navigation menu, or click here to go straight to the survey.

Antonín Dvořák

Scherzo capriccioso

✒️1883 | ⏰12 minutes

This orchestral scherzo has always been one of Dvořák’s most popular short orchestral works. Although full of light-hearted joie de vivre, it was conceived at a rather difficult point in Dvořák’s career. He was emerging from provincial obscurity on to the international scene, but found that his music – rooted in Czech folk traditions – was encountering prejudice in other central European countries, particularly Austria and Germany. A great deal of anti-Slavonic feeling had been prevalent in those countries from the 1870s onwards, and Dvořák found that Viennese audiences in particular disliked anything that smacked of nationalism. His Sixth Symphony was to have been performed under the conductor Hans Richter in Vienna in late 1880, but the performance was endlessly postponed.

England, however, welcomed Dvořák with open arms. The Sixth Symphony was conducted by August Manns in 1882, and London went wild over the Slavonic Dances and Rhapsodies. The Philharmonic Society conferred honorary membership on the composer and invited him to England in person to give concerts of his own music. At one of these, at the Crystal Palace on 22 March 1884, Dvořák conducted the London premiere of the Scherzo capriccioso, written and first performed in Prague the previous year. The piece was greeted with rapture, and Dvořák was hailed as 'the musical hero of the hour'.

Some commentators have noted a darkening of Dvořák’s musical language from the early 1880s, in response to his troubles in central Europe – the mood seems more aggressive and less sunnily 'Bohemian'. But the Scherzo capriccioso manages to combine dramatic energy with playfulness, which is part of its enduring charm. The rousing solo horn call that opens the piece deliberately begins in the 'wrong' key – B-flat major – and the orchestra is left flailing towards the home key of D-flat major. The second subject is a lilting waltz; in the middle there is a calmer melody for cor anglais in D major; while the coda, announced by a duet for horns, includes a brilliant (but rather tongue-in-cheek) harp cadenza that pays homage to Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker. Finally the solo horn once again goads the orchestra to an ebullient climax.

Note by Wendy Thompson

Antonín Dvořák

1841 – 1904 (Bohemia, now Czech Republic)

Born into a peasant family, Dvořák developed a love of folk tunes at an early age. His father inherited the lease on a butcher’s shop in the small village of Nelahozeves, north of Prague. When he was 12, the boy left school and was apprenticed to become a butcher, at first working in his father’s shop and later in the town of Zlonice. Here Dvořák learned German and also refined his musical talents to such a level that his father agreed he should pursue a career as a musician.

In 1857 he enrolled at the Prague Organ School, during which time he became inspired by the music dramas of Wagner: opera was to become a constant feature of Dvořák’s creative life. His first job was as a viola player, supplementing his income by teaching. In the mid-1860s he began to compose a series of large-scale works, including his Symphony No 1 (‘The Bells of Zlonice’) and the Cello Concerto. Two operas, a second symphony, many songs and chamber works followed before he decided to concentrate on composition. In 1873 he married one of his pupils, and in 1874 received a much-needed cash grant from the Austrian government. Brahms lobbied the publisher Simrock to accept Dvořák’s work, leading to the publication of his Moravian Duets and a commission for a set of Slavonic dances.

The nationalist themes expressed in Dvořák’s music attracted considerable interest beyond Prague. In 1883 he was invited to London to conduct a concert of his works, and he returned to England often in the 1880s to oversee the premieres of several important commissions, including his Seventh Symphony and Requiem Mass. Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor received its world premiere in London in March 1896. His Ninth Symphony (‘From the New World’), a product of Dvořák’s American years (1892–5), confirmed his place among the finest of late 19th-century composers.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Act Two from 'The Nutcracker'

✒️1891 | ⏰45 minutes

Act II

10 The Magic Castle in the Land of Sweets

11 Clara and Nutcracker Prince

12 Divertissement

----Chocolate (Spanish dance)

----Coffee (Arab dance)

----Tea (Chinese dance)

----Trepak (Russian dance)

----Dance of the Reed-pipes

----Mother Ginger

13 Waltz of the Flowers

14 Pas-de-deux

----Intrada

----Tarantella

----Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy

----Coda

15 Final Waltz & Apotheosis

Tchaikovsky’s three ballet scores all show his enormous skill in composing music which expresses and illustrates the stage situation at any given moment. His dramatic instincts led him to find exactly the right atmosphere while creating at the same time an appropriate sense of movement. He possessed the rhythmic inventiveness to create long scores full of variety, and his melodic inspiration never seems to fail. Added to his genius for rhythm and melody there is an acute sense of orchestral colour which illuminates each situation and brings it vividly to life.

To compose ballet music at all was rather unusual for a composer of Tchaikovsky’s eminence. Writing in 1875 to Rimsky-Korsakov about Swan Lake, he explained, ‘I have begun this labour partly for the money and partly because I have long wanted to try my hand at this kind of music’. 19th-century dance was above all a decorative spectacle, and the music was generally a poor affair. The composer’s contribution was entirely conditioned by the wishes of dancers and choreographers who simply wanted a series of numbers to provide a rhythmic and melodic background to the dance, but demanded little more. Larger theatres often employed staff composers who could turn out such undistinguished scores to order: ‘Market place concoctions’, Tchaikovsky called them.

Tchaikovsky was fortunate that the last years of the 19th century were a golden age for ballet at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. Two men above all were responsible for this. The first was Ivan Vsevolozhsky (1835–1909), the cultured and imaginative Director of the Russian Imperial Theatres; the second was Marius Petipa (1818–1910), the French choreographer and ballet master who had first come to St Petersburg in 1847, and from 1869 until the turn of the century ruled over the Imperial Ballet as an enlightened despot. He created a choreographic style which mixed precision with fluid movement and trained a generation of dancers many of whose names are still legendary. In 1888 Vsevolozhsky achieved his long-held ambition of commissioning a full-length ballet from Tchaikovsky. This was The Sleeping Beauty, first performed on 15 January 1890.

To follow up the success of The Sleeping Beauty and Tchaikovsky’s new opera, The Queen of Spades, at the end of the same year the Mariinsky Theatre immediately commissioned another work from Tchaikovsky. In 1891 he began working on a double-bill: the one-act opera Iolanta and the two-act ballet The Nutcracker. As with The Sleeping Beauty, Petipa provided Tchaikovsky with a detailed plan for the music, including the metre and number of bars which he required for each section. Tchaikovsky’s first reaction to the scenario he was given was tepid, but as work progressed he became increasingly involved in it.

The subject of The Nutcracker came from Vsevolozhsky, who derived a scenario quite freely from a tale by E T A Hoffmann, creating a light entertainment with little pretence at drama but full of incident and character. Act One takes place on Christmas Eve, when among their presents the children Clara and Fritz receive an odd doll in the shape of a nutcracker. Fritz treats it roughly and breaks it. Later that night, Clara witnesses a battle between her dolls and an army of mice. When she throws her shoe at the Mouse King, the Nutcracker is transformed into a handsome Prince, who transports her into a magical snowy landscape.

Act Two is set in the palace of the Sugar Plum Fairy, built entirely from sweets and other delicacies. The greater part of the act is a lavish and varied divertissement in which a series of colourful characters entertain Clara and her Prince.

Note by Andrew Huth

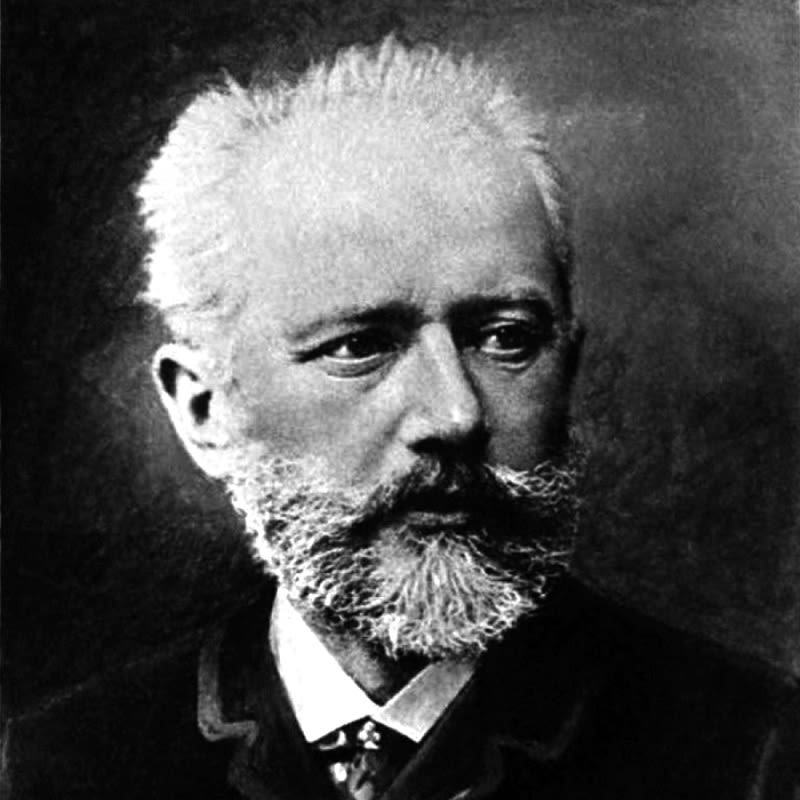

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

1840 – 1893 (Russia)

Born in Kamsko-Votkinsk in the Vyatka province of Russia on 7 May 1840, Tchaikovsky’s father was a mining engineer, his mother of French extraction. In 1848 the family moved to the imperial capital, St Petersburg, where Pyotr was enrolled at the School of Jurisprudence. He overcame his grief at his mother’s death in 1854 by composing and performing, and music remained a diversion from his job – as a clerk at the Ministry of Justice – until he enrolled as a full-time student at the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1863. His First Symphony was warmly received at its St Petersburg premiere in 1868. Swan Lake, the first of Tchaikovsky’s three great ballet scores, was written in 1876 for Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre. Between 1869 and the year of his death Tchaikovsky composed over 100 songs, cast mainly in the impassioned Romance style and textually preoccupied with the frustration and despair associated with love, conditions that characterised his personal relationships.

Tchaikovsky’s hasty decision to marry an almost unknown admirer in 1877 proved a disaster, his homosexuality combining strongly with his sense of entrapment. By now he had completed his Fourth Symphony, was about to finish his opera Eugene Onegin, and had attracted the considerable financial and moral support of Nadezhda von Meck, an affluent widow. She helped him through his personal crisis and in 1878 he returned to composition with the Violin Concerto. Tchaikovsky claimed that his Sixth Symphony represented his best work. The mood of crushing despair heard in all but the work’s third movement reflected the composer’s troubled state of mind. He died nine days after its premiere on 6 November.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Artist Biographies

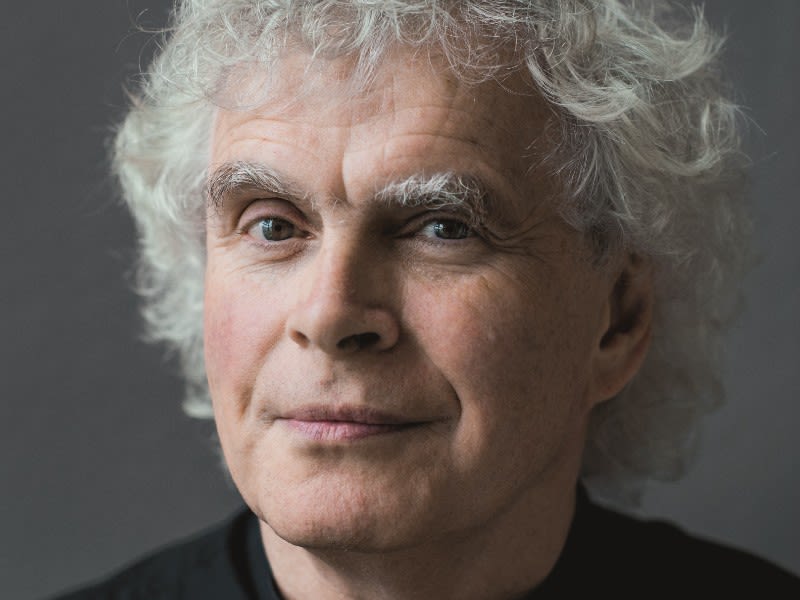

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

Sir Simon Rattle was born in Liverpool and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1980 to 1998, he was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. He moved to Berlin in 2002 and held the positions of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic until he stepped down in 2018. Sir Simon became Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and spent the 2017/18 season at the helm of both ensembles.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI record label (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance) Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortileges, Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Rachmaninoff's Symphony No 2, Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Carmine Lauri

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Claire Parfitt

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Second Violins

Julian Gil Rodriguez

Sarah Quinn

Miya Vaisanen

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Alix Lagasse

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

German Clavijo

Stephen Doman

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Jennifer Brown

Noel Bradshaw

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Double Basses

Hugh Kluger

Patrick Laurence

Matthew Gibson

Thomas Goodman

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Patricia Moynihan

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Rosie Jenkins

Cor Anglais

Maxwell Spiers

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bass Clarinet

Laurent Ben Slimane

Bassoons

Daniel Jemison

Shelly Organ

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Alexander Edmundson

Jonathan Maloney

James Pillai

Trumpets

Jason Evans

Niall Keatley

Trombones

Peter Moore

Andrew Cole

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Harp

Bryn Lewis

Anneke Hodnett

Celeste

Elizabeth Burley

Meet the Members of the LSO on our website

Thank You for Watching