London Symphony Orchestra

Grieg, Puccini, Herrmann, Barber & Vaughan Williams

Welcome and Thank You for Watching

Whilst we eagerly await our return to performing to live audiences again at our Barbican home, we are pleased to continue releasing a programme of online content and streamed broadcasts, making music available for everyone to enjoy digitally. A warm welcome to the numerous conductors and soloists joining us, among them many firm friends and regular collaborators with the Orchestra.

This concert marks the first time a large number of our freelancing friends (or 'extras') have been engaged in a concert with the LSO since March 2020, in which time the COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on their livelihoods. The Orchestra's membership is delighted to share in music-making with these extras once again.

It is a pleasure to invite you to listen today online, and we extend thanks to our partner BBC Radio 3 for broadcasting this concert. I hope you enjoy the performance, and look forward to welcoming you back in person when we are able to re-open our doors.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Herrmann, Barber & Vaughan Williams

Grieg Prelude from 'Holberg Suite'

Puccini Crisantemi

Herrmann Psycho – A Narrative for String Orchestra

Barber Adagio for Strings

Vaughan Williams Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

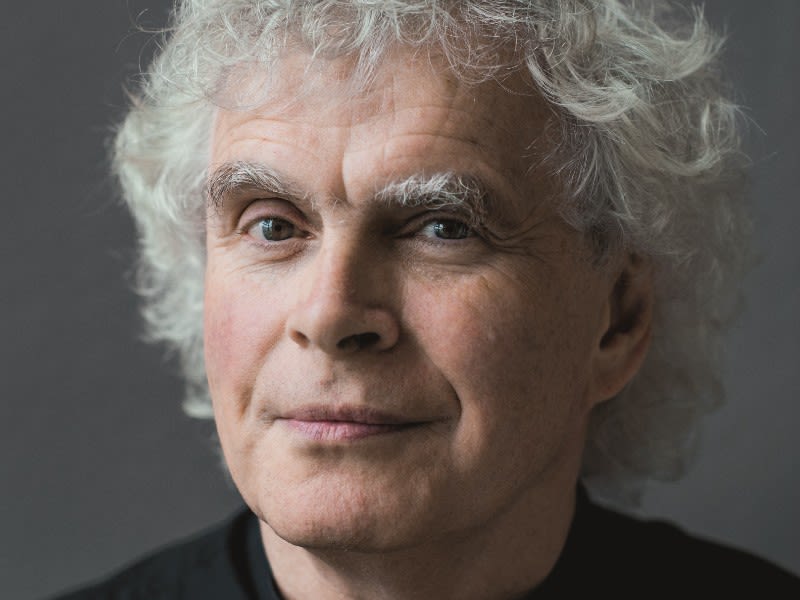

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

This performance is broadcast on BBC Radio 3.

Recorded at LSO St Luke's on 24 March in COVID-19 secure conditions.

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra, allow us to perform together again on stage and to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO’s return to work is supported by DnaNudge.

Generously supported by the Weston Culture Fund.

Share Your Thoughts

We always want you to have a great experience, however you watch the LSO. Please do take a few moments at the end to let us know what you thought of the streamed concert and digital programme. Just click 'Share Your Thoughts' in the navigation menu.

Today's concert marks the first time a large number of extras have been engaged in a full-scale symphony concert with the LSO since March 2020.

'The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on musicians in the UK, and ongoing restrictions have meant many of those without permanent contracts face further months without work. This special concert is one small step on the road to recovery and a call out to encourage friends and colleagues to see where they can find opportunities for freelancers to play again.'

Sir Simon Rattle, LSO Music Director

Reduced hours for freelancing musicians have been caused in large part by the cancellation of many concerts when the first lockdown began. Industry-wide performance opportunities continue to be fewer. Since live concerts and recordings behind closed doors have resumed, social distancing measures mean fewer players are able to fit safely into the same space.

For the LSO’s final concert before lockdown on 15 March 2020, 90 players performed on the Barbican stage. That number decreased to 62 in the Jerwood Hall, LSO St Luke’s, for the LSO’s first full orchestral engagement of the 2020/21 season on 2 September 2020, with a number of those unable to fit into the main hall and required to play from the balcony.

‘It is with excitement and enthusiasm that we reunite with many of the ‘extras’ we have played alongside for years, sharing in music-making once again. We have been lucky as Members to be able to continue recording our programme of concerts. But our extended family of invited freelance musicians have missed out. They are key to putting on our rich and varied programme of performances each year, and they have been sorely missed.’

David Alberman, LSO Chair and Principal Second Violin

Edvard Grieg

Prelude from 'Holberg Suite'

✒️1884 rev 1885 | ⏰3 minutes

The celebrated playwright, essayist and historian Ludwig Holberg was born in Bergen, Norway, in 1684. Two hundred years later, the composer Edvard Grieg, also from Bergen, set about creating a suite of music to mark his fellow countryman’s bicentenary. Modelled on the keyboard suites of Holberg’s era, using Baroque dance forms such as the sarabande, gavotte and rigaudon, it evokes the grace and courtliness of 17th-century music. The Prelude is the first movement, opening the suite by unfurling a theme that is more harmonic progression than melody. Grieg then floats a lyrical line over the top, high on the violins, and introduces passages of contrast and conversation, as if filtering the past through a prism for the 19th-century present.

The Holberg Suite was originally for piano; in this guise Grieg himself premiered it at Bergen’s Holberg celebrations in December 1884. The following year, creating a version for string orchestra, he entirely reimagined the Prelude's figurations to suit the new instrumentation.

Note by Jessica Duchen

Edvard Grieg

1843–1907 (Norway)

'Artists such as Bach and Beethoven erected churches and temples in ethereal heights. In my music my aim is exactly what Ibsen says about his plays: 'I want to build homes for the people in which they can be happy and contented'.'

Edvard Grieg

Edvard Grieg's mother, an accomplished pianist, was among the leading musical figures of Bergen, on the west coast of Norway. His father, of Scottish descent, served as British consul in the city and was also a keen amateur musician. They encouraged Edvard's musical talent, and from the age of six he received piano lessons from his mother. In 1858 the virtuoso violinist Ole Bull heard Grieg play and urged the 15-year-old to enrol at the Leipzig Conservatory. After his studies in Germany, Grieg returned to Bergen and established his reputation as a pianist; he then lived for a short period in Copenhagen. In 1867 he married his cousin Nina Hagerup, a singer.

In the late 1860s Grieg set about raising his stock in the Norwegian capital, Christiania (Oslo), a small city then with little appreciation of culture. 'Everyone hates my music,' he wrote in July 1867, 'even the professional musicians.' Later that year he completed his first set of Lyric Pieces for piano, several of which reveal an emerging nationalist style. Recognition in Norway came in the early 1870s and in 1874 Grieg received a lifetime stipend from the Norwegian government. The first performance of playwright Henrik Ibsen's drama Peer Gynt in 1876, with incidental music by Grieg, made the composer a figure of national importance. A series of fine works followed, including the Holberg Suite and nine further albums of Lyric Pieces, all evincing Grieg's characteristic blend of Romantic lyricism and aspects of native folk music. His gift lay in the expression of intense emotion in works of often miniature proportions, as well as the creation of lyrical melodies.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Giacomo Puccini

Crisantemi

✒️1890 | ⏰6 minutes

The chrysanthemum (crisantemo in Italian) is a flower associated in Italian culture with mourning – a signal as to the intent of Giacomo Puccini's Crisantemi, the one piece of his for string quartet that is widely known. The piece came into being in a single night in January 1890 as his response to the sudden death of a friend, Amadeo di Savoia, Duke of Aosta, who in the 1870s had briefly been the King of Spain. Puccini was 31 and his career was still in its early stages. His opera Edgar had flopped the previous year and now he was struggling with ill-fated revisions.

The single movement, its atmosphere replete with tragedy, is based on two plaintive ideas, the first a theme that expands in opposite directions, the other a lament reminiscent of an aria (a song for solo voice common in operas). So operatic was Crisantemi – and so pragmatic the composer, at heart – that three years later both themes from the piece popped up again in his opera Manon Lescaut. In that incarnation, this music helped to propel Puccini to his first major triumph, setting him on the path to fame and fortune.

Note by Jessica Duchen

Giacomo Puccini

1858 (Italy) – 1924 (Belgium)

Descended from four generations of Tuscan municipal musicians, Puccini learned the family trade from his uncle before earning a place at the prestigious conservatory of music in Milan, even when he was well past the usual age limit for admissions. He was never a model student. Despite his talent, Puccini was lazy and always open to distraction.

From early attempts at writing opera (Le Villi and Edgar), and after breaking through with Manon Lescaut, Puccini enjoyed a long and successful career as one of the most popular musicians of his day, and is now recognised as the greatest Italian opera composer since Verdi.

But that reputation rests on a slim output of just eight full-length operas, three one-acts and one unfinished work, written over four decades with only minor works between. Not that Puccini was meticulous, but he never managed to shake the idleness that plagued him his whole life. He always spent too little time actually writing music, and too much time fishing and hunting, travelling to oversee new productions, collecting cars, houses and boats, going to the theatre, or pursuing married women and risking scandal.

In fact, Puccini’s love for life, people, places and things might be why the music he did manage to write has such a strong hold on our imagination. The human dimension to his work sings out to us so strongly even now, especially in his three most popular operas: La bohème, Tosca and Madame Butterfly. For all its musical sophistication, for all the finely-crafted melodies and rich Romantic harmony, Puccini’s music endures because it seems to express something timeless and essential. We all see something of ourselves in his characters; we all hear our hopes and our dreams played out in his scores.

Composer profile by Mark Parker

Bernard Herrmann

Psycho – A Narrative for String Orchestra

✒️1968 | ⏰15 minutes

As Alfred Hitchcock’s right-hand composer for nine classic movies between 1955 and 1966, Bernard Herrmann produced film music of genius, creating the intense, complex atmospheres against which the dramas unfurled.

Psycho (1960) is perhaps the most inspired of all. A young woman on the run arrives at the sinister Bates Motel, where the proprietor, Norman, murders her in the shower. The film gradually unveils the degree of Norman’s psychosis, culminating in a gut-wrenching revelation. It was shot in black and white, and Herrmann set out to create a sound to mirror this. He found the solution in a string orchestra, describing it as 'the sound of pure ice-water'. Speaking of water, Hitchcock at first asked the composer not to score the shower scene. Herrmann quietly disobeyed and thus had an unforgettable stretch of music to present when Hitchcock changed his mind.

After falling out with Hitchcock, Herrmann began to prepare concert versions of his film-scores, which otherwise existed only on celluloid. In his ‘Narrative’ of Psycho, created in 1968, he spliced together elements of the score into effectively a symphonic poem. Although he recorded it, he did not perform the work, and for many years it was as good as lost. The conductor John Mauceri set about a reconstruction from photocopies of Herrmann’s notes on the cues, while preparing for a Hitchcock centenary concert in 1999. He gave the premiere in Los Angeles on 9 February 2000 and further revised the score according to Herrmann’s bowings in 2013.

The narrative clearly follows the film’s action: Marion’s theft, her flight to the motel ('The music is telling us that something terrible is going to happen to her, it’s got to,' said the composer) and the stabbing; Norman disposes of her body, murders the detective on his trail and is ultimately caught and imprisoned. Listen for the shrieking violins, which seem to serve three filmic purposes simultaneously: the screams of the victim, the stabbing rhythm of the knife attack and the former cries of the stuffed birds with which Norman has filled his room. Asked what he was trying to evoke, Herrmann said simply: 'Terror'.

Note by Jessica Duchen

Bernard Herrmann

1911–75 (US)

BMI/Michael Ochs Arvhives/Getty Images

BMI/Michael Ochs Arvhives/Getty Images

Born in New York City in 1911, Bernard Herrmann was encouraged in the arts from an early age by his father. He would later cite Hector Berlioz's Treatise on Orchestration, which he discovered aged 13, as the book that decided his future career. He began studying composition and conducting at NYU in 1929, before continuing studies at Juilliard and joining the Young Composers Group, headed by Aaron Copland. In these years he acquired a particular taste for unique composers and neglected scores, an interest which lectures from eccentric musicologist and composer Percy Grainger served to heighten.

Herrmann was appointed to CBS Radio in 1934 to work as a composer, arranger and conductor. Through his work on drama series Mercury Theatre on the Air, directed by Orson Welles, he was subsequently invited to compose and conduct the music for Welles' first film, Citizen Kane (1941). The highly successful film music career for which Herrmann is remembered followed: he was hired to write numerous scores by 20th Century Fox music director Alfred Newman in the 1940s, and in the 1950s established his famed partnership with Alfred Hitchcock, resulting in the unmistakeable and iconic music for Psycho (1960).

Herrmann nevertheless rejected the term 'film composer', noting that many great composers can count among their creative output scores for cinema (Copland, Shostakovich and Walton for example). The same is true of Herrmann – alongside an influential catalogue of major film scores, he also composed a number of successful concert works before his death in 1975.

Samuel Barber

Adagio for Strings

✒️1938 | ⏰8 minutes

'If Barber, 25 years old when it was completed, later reached higher, he never reached deeper into the heart.' So wrote Ned Rorem of Barber’s Adagio for Strings, and indeed, this remarkable music bears a simplicity and directness that seems to hold universal appeal.

Gradually it has acquired associations with mourning, played in a radio broadcast after the funeral of John F Kennedy, at the reformatted Last Night of the Proms after 9/11 and in the US ceremony that marked that day’s destruction of the World Trade Center.

'My aim is to write good music that will be comprehensible to as many people as possible, instead of music heard only by small, snobbish musical societies in the large cities'.

Samuel Barber

At the time he wrote it, the precocious composer was an experienced musician despite his scant quarter-century, having started out as a much-encouraged prodigy. He assured his parents, aged ten: 'I was meant to be a composer and will be. Do not ask me to forget this ‘thing’ and go play football, please!' After studies at the Curtis Institute, he won the Prix de Rome in 1935, plus two Pulitzer Fellowships. There was every reason for the conductor Arturo Toscanini to be interested in his work. At Toscanini’s request, Barber arranged for string orchestra the Adagio of his String Quartet No 1, which he had written in Europe during summer 1936. Toscanini and his NBC Symphony Orchestra premiered it on 5 November 1938; the broadcast reached an exceptionally wide audience, winning the work immediate success.

The slowly unfurling idea at the start is the basis for the whole piece, setting up a meditative atmosphere in a language almost reminiscent of monastic plainchant. Barber controls the pace and intensity in one long span, carrying it through an extended build-up to a high-set climax and shattering silence, before the opening music returns.

Note by Jessica Duchen

Samuel Barber

1910–81 (US)

Bettmann/Corbis

Bettmann/Corbis

Given the enormous success he enjoyed during his career, it is puzzling that Samuel Barber is now remembered primarily for just one work – his Adagio for Strings (1938). His catalogue of music, though not as extensive as some of his contemporaries, extends from solo piano music and instrumental chamber works to symphonies, concertos and operas. He was twice awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music, in addition to the American Prix de Rome, and in 1966 he was commissioned to write a new opera to mark the opening of the Metropolitan Opera’s new home at the Lincoln Center (the production was a flop, but this was largely thanks to Zeffirelli’s direction, rather than Barber’s music).

Barber’s relative neglect from the 20th century canon probably owes much to his musical style. While Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School forged new harmonic paths through atonality and serialism, and Stravinsky explored bold new levels of dissonance, rhythmic vitality and texture, Barber seemed to content to follow his own path, one which owed more to the dying strains of Romanticism than to the radical new sound world of the 20th century. That is not to say that Barber’s music is not innovative and dramatic, nor that his often complex and dissonant harmonies can be considered ordinary, but the rich, full textures of his works with their predilection for sweeping, generous melodies sets them apart from many of the more experimental trends of his age.

Composer profile by Jo Kirkbride

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

✒️1910 | ⏰14 minutes

Smaller String Ensemble Musicians

First Violins

William Melvin

Laurent Quénelle

Second Violins

David Ballesteros

Naoko Keatley

Violas

Anna Bastow

Sofia Silva Sousa

Cellos

Alastair Blayden

Daniel Gardner

Double Bass

Patrick Laurence

Click or scroll to 'On Stage' to see a full list of musicians performing in this concert.

Vaughan Williams’ most famous fantasia sprang from a combination of passions: his absorption in Tudor music and English folk song, collecting, and from his editorship of The English Hymnal, which occupied him almost exclusively from 1904 to 1906. Several of the tunes included in the hymnal influenced his own subsequent compositions, including the third of nine Psalm tunes by the Elizabethan composer Thomas Tallis, originally printed in Archbishop Parker’s metrical psalter of 1567. This melody is set in The English Hymnal to Addison’s words ‘when rising from the bed of death’.

In 1910, Vaughan Williams was commissioned to write a piece for the Three Choirs Festival, to be performed in Gloucester Cathedral alongside fellow composer Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius. Elgar’s use some five years earlier of the combination of string quartet and string orchestra in his Introduction and Allegro almost certainly prompted Vaughan Williams to employ the same forces in his Fantasia based on Tallis' psalm melody.

He conducted the strings of the London Symphony Orchestra at the work’s premiere on 6 September 1910. On the whole, the critics received it coolly, and after its London premiere in February 1913, Vaughan Williams withdrew it for substantial revision. It took another two decades for the work to be recognised as a minor masterpiece, and it has since been one of the composer’s most popular and frequently performed pieces.

The fantasia is scored for double string orchestra of unequal size (the second consists of only nine players), from which the section leaders emerge as a solo quartet. Vaughan Williams took as his starting point Tallis’ original harmonisation of his modal melody, and based his structure on the sectional concept of the Tudor fantasia. The theme itself appears in various embellished guises before reappearing in its original grandeur in the closing section.

Note by Wendy Thompson

Ralph Vaughan Williams

1872–1958 (UK)

Born in Gloucestershire on 12 October 1872, Ralph Vaughan Williams moved to Dorking in Surrey at the age of two, on the death of his father. Here, his maternal grandparents, Josiah Wedgwood – of the pottery family – and his wife Caroline, who was the sister of Charles Darwin, encouraged a musical upbringing. Vaughan Williams attended Charterhouse School, and in 1890 he enrolled at the Royal College of Music, becoming a pupil of Sir Hubert Parry. Weekly lessons at the RCM continued when he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1892.

Vaughan Williams’s first composition to make any public impact, the song Linden Lea, was published in 1902. His ‘discovery’ of folk song in 1903 was a major influence on the development of his style. A period of study with Maurice Ravel in 1908 was also very successful, with Vaughan Williams learning, as he put it, ‘how to orchestrate in points of colour rather than in lines’. The immediate outcome was the song-cycle On Wenlock Edge. The Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis was first performed in Gloucester Cathedral in 1910. With these works he established a reputation which subsequent compositions, such as the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony, Flos Campi and the Mass in G minor, served to consolidate.

In 1921 he became conductor of the Bach Choir, alongside his Professorship at the RCM. Over his long life, he contributed notably to all musical forms, including film music. It is in his nine symphonies however, spanning a period of almost 50 years, that the greatest range of musical expression is evident. Vaughan Williams died on 26 August 1958, just a few months after the premiere of his Ninth Symphony.

Composer profile by Stephen Connock

Artist Biographies

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

Sir Simon Rattle was born in Liverpool and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1980 to 1998, he was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. He moved to Berlin in 2002 and held the positions of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic until he stepped down in 2018. Sir Simon became Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and spent the 2017/18 season at the helm of both ensembles.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI record label (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance) Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortileges, Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives, Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic *

First Violins

Clare Duckworth *

Laura Dixon *

Gerald Gregory *

William Melvin *

Claire Parfitt *

Elizabeth Pigram *

Laurent Quénelle *

Harriet Rayfield *

Sylvain Vasseur *

Marciana Buta

Lyrit Milgram

Grace Lee

Alexandra Lomeiko

Dániel Mészöly

Hilary Jane Parker

Erzsebet Racz

Patrick Savage

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez *

Sarah Quinn *

Miya Väisänen *

David Ballesteros *

Matthew Gardner *

Naoko Keatley *

Alix Lagasse *

Iwona Muszynska *

Ingrid Button

Eleanor Fagg

Caroline Frenkel

Raja Halder

Gordon MacKay

Greta Mutlu

Robert Yeomans

Violas

Rachel Roberts

Malcolm Johnston *

Anna Bastow *

German Clavijo *

Stephen Doman *

Sofia Silva Sousa *

Robert Turner *

Michelle Bruil

Luca Casciato

May Dolan

Nancy Johnson

Jenny Lewisohn

Alistair Scahill

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver *

Alastair Blayden *

Jennifer Brown *

Noël Bradshaw *

Daniel Gardner *

Laure Le Dantec *

Amanda Truelove *

Judith Fleet

Ghislaine McMullin

Desmond Neysmith

Victoria Simonsen

Double Basses

David Stark

Patrick Laurence *

Thomas Goodman *

Joe Melvin *

José Moreira *

Benjamin Griffiths

Siret Lust

Paul Sherman

Simo Väisänen

Adam Wynter

* denotes LSO Member

Meet the Members of the LSO on our website

Thank You for Watching