LSO Half Six Fix

Mahler 4

Wednesday 8 December 2021 6.30pm

Digital Concert Guide

Welcome to tonight's Half Six Fix, a different way to experience the London Symphony Orchestra, with introductions from conductor Kirill Karabits and LSO Second Violin Belinda McFarlane.

YOUR DIGITAL CONCERT GUIDE

You can use your phone to view this digital guide during the concert, and discover more about the music and performers.

Navigate using the menu icon (≡) at the top of the screen.

There is free WiFi in the Concert Hall, available through the Barbican Free WiFi network.

So that everyone can have the best experience, please set your phone to silent and don’t use other apps during the music. Photos can be taken during applause at the end of the concert.

Structure your listening with the Visual Listening Guide

The Guide is designed to act as a map of important sonic landmarks in the Symphony, showing where the main musical themes and moments occur in a visually engaging way, whatever your musical background!

NB The licence to the Visual Listening Guide has now expired, but is available to purchase from the Symphony Graphique website with a 20% discount using the code LSOMAH20 at the checkout.

Opens in a new tab

Tonight's Programme

Gustav Mahler Symphony No 4

Kirill Karabits conductor & presenter

Lucy Crowe soprano

London Symphony Orchestra

NB Change of Conductor

Sir Simon Rattle has tested positive for COVID-19 and unfortunately is unable to fulfil his engagements with the LSO this month. He is currently isolating at home, with mild symptoms.

We are pleased that Kirill Karabits has agreed to step in as conductor. Tonight's programme remains unchanged.

‘Music is capable of reproducing, in its real form, the pain that tears the soul and the smile that it inebriates.’

Symphony No 4 in G Major

✒️1899–1900 | ⏰60 minutes

1 Bedächtig, nicht eilen (Deliberate. Not hurried) – Recht gemächlich (Very leisurely)

2 In gemächlicher Bewegung, ohne Hast (At a leisurely pace. Without haste)

3 Ruhevoll: poco adagio (Restful)

4 Sehr behaglich (Very cosy)

Why is it that the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, more than those of any other composer, have become the benchmark by which orchestras around the world are judged?

It’s partly to do with the kaleidoscopic philosophical and expressive range driven by his all-embracing outlook. The symphony, Mahler famously said, had to ‘be like the world. It must embrace everything.’ His symphonies are accordingly strewn with references to nature and death (and the beyond) but contrasted with everyday sounds such as folk music, military fanfares or marching bands. Mahler’s symphonies are more than the playthings of a self-styled, egotistical Romantic hero: they resonate with us because his preoccupations – joy, fear, terror, love, humour and death – are also our own.

'A symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.'

Mahler expanded the size of the symphony orchestra to new limits, often with quadruple wind (four each of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons, as opposed to two each in the typical Classical-period orchestra). He also pushed the boundaries of harmony, to the extent that the only next step, instigated by Arnold Schoenberg, was to explode the idea altogether, ushering in a dystopian, anti-harmonic world of ‘atonality’. In all these ways, Mahler elevated the symphony, so it’s no wonder that orchestras and conductors queue up to scale its heights.

At ‘only’ around an hour in length, Mahler’s Fourth is bijou compared to his mammoth Second and Third Symphonies (which run to around 80 minutes and 100 minutes respectively). It is the only one of his nine symphonies not to feature trombones or tuba. As in those two previous symphonies, he returned to one of his songs on texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn) – a German folk-poetry collection that was popular among German Romantics. Das himmlische Leben (Heavenly Life) became the Fourth Symphony’s finale. It presents an idyllic view of heaven, where there is dance and song, free-flowing wine, an abundance of fresh produce and, not insignificantly, unearthly music overseen by Saint Cecilia (the patron saint of music) herself.

There are allusions to childlike simplicity in the first movement, with its sleigh-bell opening, its carefree, often lyrical, themes and its tendency to move quickly from one idea to another. After a high, whistling theme on flutes, the music becomes streaked with darker visions – alarming and grotesque – like all the best children’s tales. All this eventually relaxes in a blissful reverie. The movement’s first theme (now familiar) slowly emerges again and gathers pace towards a brief ‘and that was that’ end.

Mahler originally titled the second movement ‘Death strikes up the dance for us’. A slow-whirling Ländler (a rustic version of the waltz) brings a macabre solo on a violin whose four strings are tuned a tone higher than usual. A more relaxed episode, with fluttering wind instruments, twice alternates with the Ländler.

The third movement is the lyrical heart of the symphony. Every bit as beautiful as the better-known slow movement (Adagietto) of the Fifth Symphony, its broadly arching first theme is carried by a gentle, plucked tread that both marks time and somehow also suspends it. A second theme is more troubled, the tread now more urgent, and a range of emotional ground is covered in various guises of the first theme. In the climactic outburst near the end, horns briefly foreshadow the opening theme of the finale, but the ending brings a sense of spiritual or physical transfiguration, and the violins rise celestially …

Then comes the child’s view of heaven, ‘to be sung,’ Mahler directs, ‘in a happy childlike manner: absolutely without parody’. But, as ever with Mahler, there’s a dark undercurrent – expressing the realities of a lamb and the oxen slaughtered for food. There is no grand affirmation but instead a journey into the distance.

Programme note by Edward Bhesania

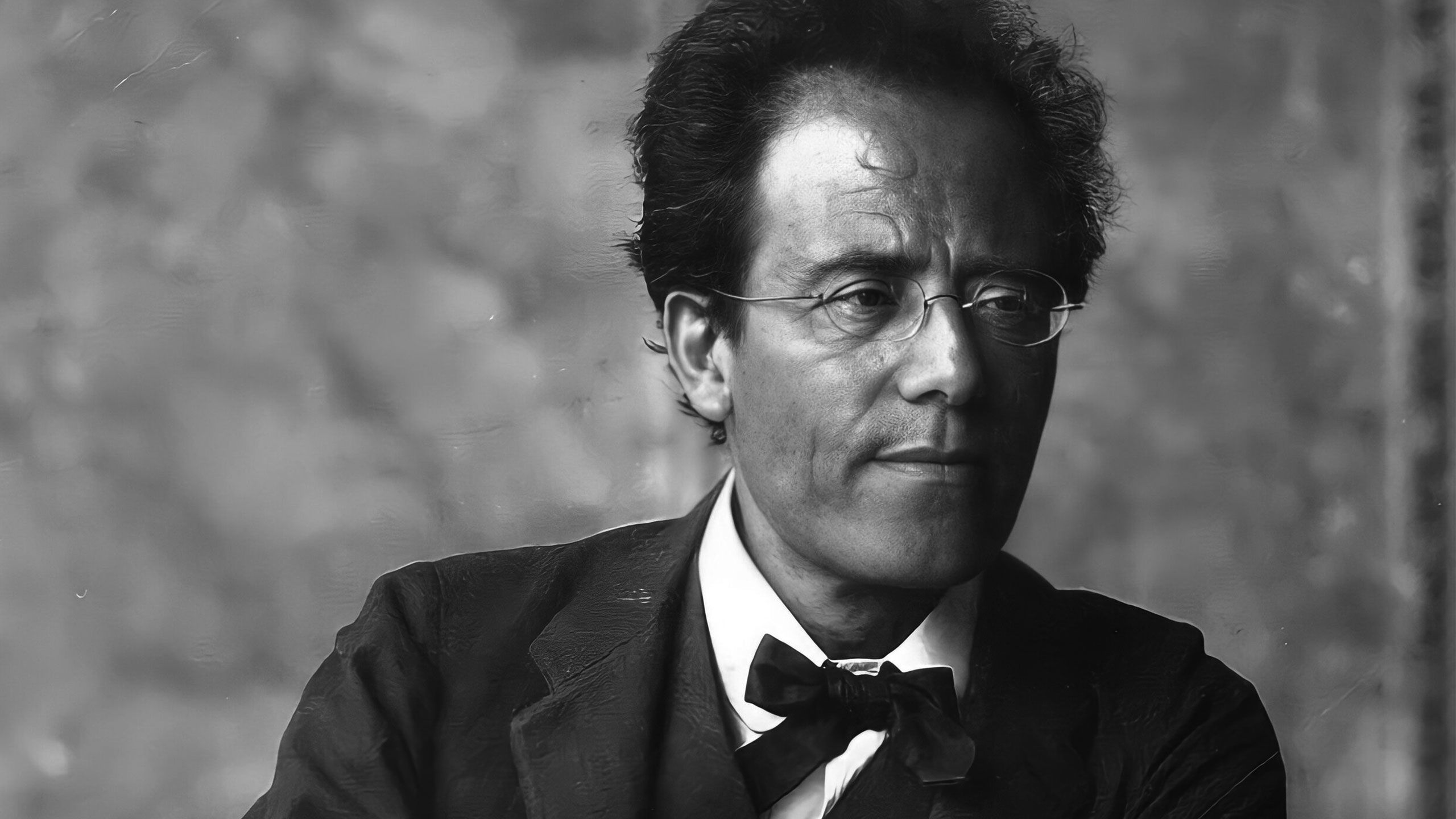

Gustav Mahler

1860 (Bohemia) to 1911 (Austria)

More than any composer since Ludwig van Beethoven, Gustav Mahler radically altered the course of symphonic form, broadening its scale and instrumentation, imbuing it with vast emotional range and incorporating autobiographical references. Born in Bohemia, he went to study in Vienna at the age of 15, before developing a conducting career in a succession of opera theatres.

In 1897 he became Kapellmeister at the Vienna Court Opera, converting from Judaism to Catholicism in order to do so. The demands of his conducting commitments left only the summers for composing, when he would retreat to the mountains and lakes. He was heavily drawn to the folk-like poetry collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn, 1808), writing over 20 Wunderhorn songs and incorporating some into his Symphonies Nos 2 to 4. Five of Mahler’s siblings died in infancy, as did his own elder daughter – lending further poignancy to his Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children, 1904).

He worked in New York at the Metropolitan Opera and Philharmonic Orchestra, but fell victim to heart disease: he died before completing his tenth numbered symphony, soon after the bitter discovery of his wife Alma’s affair with the architect Walter Gropius.

LSO Music Director Rattled by Mahler

It was the ‘totally transfiguring experience’ of hearing Mahler – the Second Symphony – as an 11-year-old in Liverpool that inspired the London Symphony Orchestra's Music Director Simon Rattle to take up the baton.

‘My incurable virus – the wanting-to-conduct-Mahler virus – started there and then,’ Rattle has said. ‘It’s because of that evening that I’m a conductor.’

Transported to an Alternative Plane

Rattle was in an airport lounge when he started looking at the newly published performing version of Mahler’s incomplete 10th Symphony. It proved a distraction. ‘I missed the last plane to Glasgow,’ Rattle confessed. ‘So foolish! I had to stay in the airport hotel and take the first flight the next day. All because of Mahler.’

Hearing Voices

Mahler’s Fourth Symphony wasn’t his first to feature voices. While Beethoven called for solo voices and chorus only in his Ninth and final symphony, Mahler incorporated voices into four of his numbered symphonies:

Symphony No 2: soprano and alto soloists, plus choir

Symphony No 3: alto soloist, plus female choir and boys’ choir

Symphony No 4: soprano soloist

Symphony No 8: three sopranos, two altos, tenor, baritone and bass soloists, plus two choirs and a children’s choir

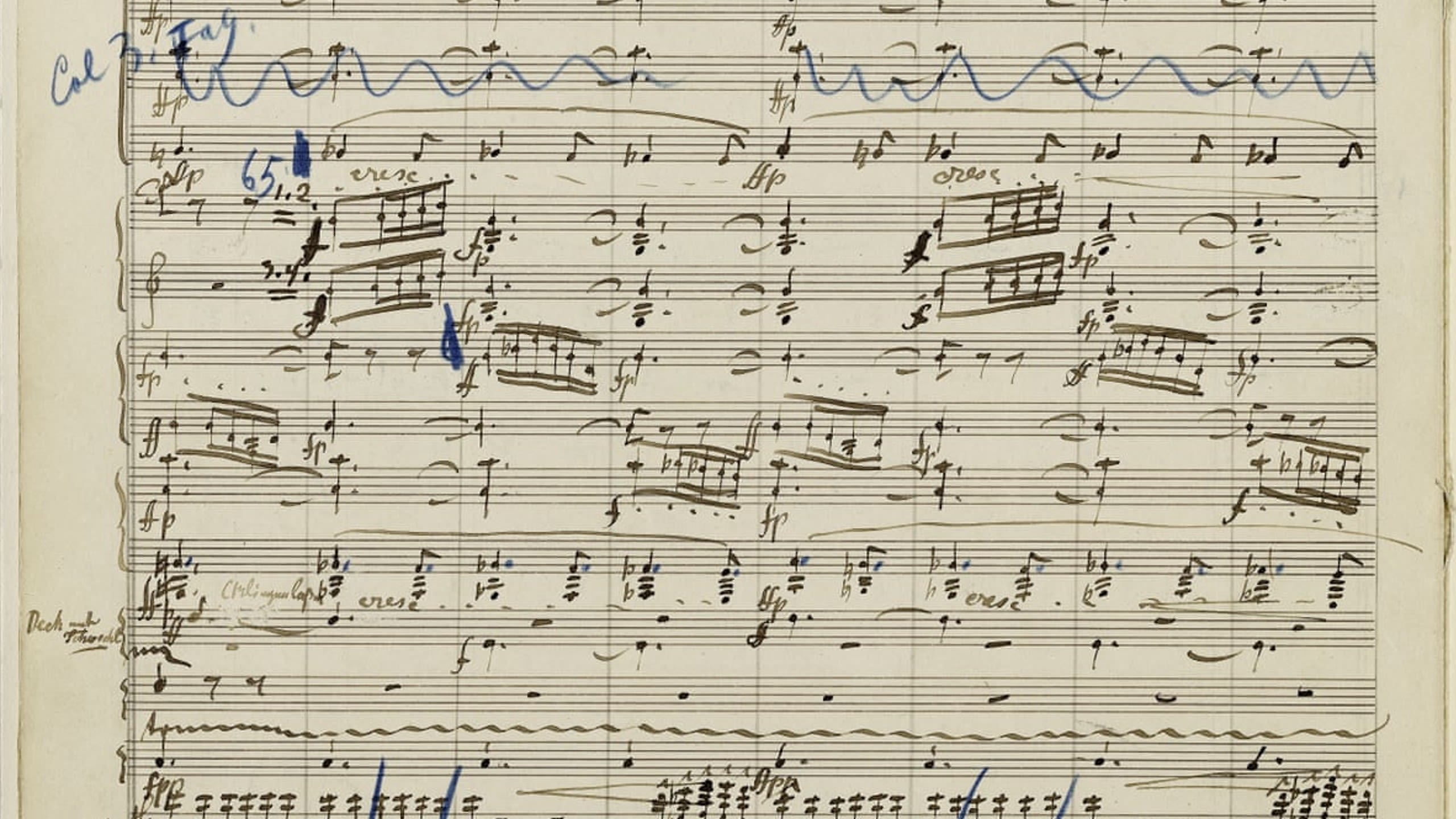

Notes for Notes

In 2016, Mahler’s autographed manuscript of his Second Symphony sold at Sotheby’s in London for £4,546,250, becoming the most expensive music manuscript ever to be sold at auction.

Image: Sothebys

One Ninth, no Tenth

The 'curse of the ninth symphony' loomed over composers from the 19th century onwards, based on the fact that a number of them – Schubert, Beethoven, Dvořák and Bruckner included – subsequently failed to complete a tenth. After composing his Eighth Symphony, Mahler refused to label his next one ‘No 9’ (he instead called it Das Lied von der Erde, The Song of the Earth). Having later completed a Symphony No 9, and thinking he had defied fate, he died before completing his No 10.

Text & Translation

Das himmlische Leben

The heavenly life

Wir geniessen die himmlischen Freuden,

Drum tun wir das Irdische meiden,

Kein weltlich Getümmel

Hört man nicht im Himmel!

Lebt alles in sanftester Ruh’!

Wir führen ein englisches Leben!

Sind dennoch ganz lustig daneben!

Wir tanzen und springen,

Wir hüpfen und singen!

Sankt Peter im Himmel sieht zu!

We enjoy the heavenly pleasures

and avoid earthly things.

No worldly tumult

can be heard in Heaven!

Everything lives in the sweetest peace!

We lead an angelic life!

Nevertheless we are very merry:

we dance and leap,

hop and sing!

Meanwhile, St Peter in the sky looks on.

Johannes das Lämmlein auslasset,

Der Metzger Herodes drauf passet!

Wir führen ein geduldig’s,

Unschuldig’s, geduldig’s,

Ein liebliches Lämmlein zu Tod!

Sankt Lucas den Ochsen tät schlachten

Ohn’ einig’s Bedenken und Achten,

Der Wein kost’ kein Heller

Im himmlischen Keller,

Die Englein, die backen das Brot.

St John has let his little lamb go

and the butcher Herod looks on!

We lead a patient,

innocent, patient,

a dear little lamb to death!

St Luke slaughters oxen

without giving it thought or attention.

Wine costs not a penny

in Heaven’s cellar;

and the angels bake the bread.

Gut’ Kräuter von allerhand Arten,

Die wachsen im himmlischen Garten!

Gut’ Spargel, Fisolen

Und was wir nur wollen!

Ganze Schüsseln voll sind uns bereit!

Gut Äpfel, gut’ Birn’ und gut’ Trauben!

Die Gärtner, die alles erlauben!

Willst Rehbock, willst Hasen,

Auf offener Straßen

Sie laufen herbei!

Good vegetables of all sorts

grow in Heaven’s garden!

Good asparagus, beans

and whatever we wish!

Bowls are heaped full, ready for us!

Good apples, good pears and good grapes!

The gardener permits us everything!

Would you like roebuck, would you like hare?

They run free

In the very streets!

Sollt’ ein Fasttag etwa kommen,

Alle Fische gleich mit Freuden angeschwommen!

Dort läuft schon Sankt Peter

Mit Netz und mit Köder

Zum himmlischen Weiher hinein.

Sankt Martha die Köchin muß sein.

Should a fast-day arrive,

all the fish swim up to us with joy!

Then off runs St Peter

with his net and bait

to the heavenly pond.

St Martha must be the cook.

Kein’ Musik ist ja nicht auf Erden,

Die uns’rer verglichen kann werden.

Elftausend Jungfrauen

Zu tanzen sich trauen!

Sankt Ursula selbst dazu lacht!

Cäcilia mit ihren Verwandten

Sind treffliche Hofmusikanten!

Die englischen Stimmen

Ermuntern die Sinnen,

Dass alles für Freuden erwacht.

No music on earth

can be compared to ours.

Eleven thousand maidens

dare to dance!

Even St Ursula herself is laughing!

Cecilia and all her relatives

make splendid court musicians!

The angelic voices

rouse the senses

so that everything awakens with joy.

Translation anonymous

Tonight's Artists

Kirill Karabits

conductor

Kirill Karabits has been Chief Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra for 13 years and their relationship has been celebrated worldwide.

Kirill has worked with many of the leading ensembles of Europe, Asia and North America, including the Cleveland, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Chicago Symphony orchestras, Munich Philharmonic, Orchestre National de France, Philharmonia Orchestra, Vienna Symphony, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra Filarmonica del Teatro La Fenice and the BBC Symphony Orchestra – including a concertante version of Bartók's Duke Bluebeard’s Castle at the Barbican. Kirill enjoys a special relationship with the Russian National Orchestra with whom he returned to the Edinburgh Festival in the 2018/19 season, and more recently embarked on extensive European and North American tours with Mikhail Pletnev which included his New York debut at the Lincoln Center.

A prolific opera conductor, Kirill has worked with the Deutsche Oper, Opernhaus Zürich and Oper Stuttgart , Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Staatsoper Hamburg, English National Opera, Bolshoi Theatre and he conducted a performance of The Flying Dutchman at the Wagner Geneva Festival in celebration of the composer’s anniversary. Music Director of the Deutsches Nationaltheatre Weimar from 2016–19, Kirill conducted acclaimed productions of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Tannhäuser as well as Mozart's DaPonte Cycle (The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte).

Working with the next generation of bright musicians is of great importance to Kirill. As Artistic Director of I, CULTURE Orchestra he conducted them on their European tour in August 2015 with Lisa Batiashvili as soloist and a summer festivals tour in 2018, including concerts at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and the Montpellier Festival. In 2012 and 2014 he conducted the televised finals of the BBC Young Musician of the Year Award (working with the Royal Northern Sinfonia and BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra), and has recently debuted with the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain on a UK tour including a sold out and critically acclaimed performance at the Barbican.

Kirill was named Conductor of the Year at the 2013 Royal Philharmonic Society Music Awards.

Lucy Crowe

soprano

Born in Staffordshire, Lucy Crowe studied at the Royal Academy of Music, where she is a Fellow.

With repertoire ranging from Purcell, Handel and Mozart to Donizetti’s Adina (L’elisir d’amore), Verdi’s Gilda (Rigoletto) and Janáček's Vixen (The Cunning Little Vixen) she has sung with opera companies throughout the world, including the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, the Glyndebourne Festival, English National Opera, the Teatro Real Madrid, the Deutsche Oper Berlin, the Bavarian State Opera, Munich and the Metropolitan Opera New York.

In concert, she has performed with many of the world's finest conductors and orchestras including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (with Emmanuelle Haïm, Sakari Oramo and Andris Nelsons), the Berlin Philharmonic (Daniel Harding and Nelsons), Vienna Philharmonic (Nelsons), Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (Richard Egarr), Scottish Chamber Orchestra (Yannick NézetSéguin), the Monteverdi Orchestra (Sir John Eliot Gardiner), the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (Sir Antonio Pappano) and the London Symphony Orchestra (Sir Simon Rattle).

Her recordings include Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang with the LSO and Gardiner; Handel’s Il Pastor Fido and Handel & Vivaldi with La Nuova Musica and David Bates for Harmonia Mundi; Lutoslawski with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Gardner, Handel’s Alceste with the Early Opera Company and Christian Curnyn, and Eccles’ The Judgement of Paris all for Chandos; a solo Handel disc – ll Caro Sassone – with The English Concert and Harry Bicket for Harmonia Mundi, and Handel’s Queens with London Early. Her debut disc for Linn records featuring Berg, Strauss and Schoenberg was released in August 2021.

London Symphony Orchestra

At the London Symphony Orchestra we strive to inspire hearts and minds through world-leading music-making. We were established in 1904, as one of the first orchestras shaped by its musicians.

Through inspiring music, a world-leading learning and community programme and technological innovations, our reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

On Stage

Guest Leader

Sergey Ostrovsky

First Violins

Janice Graham

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Claire Parfitt

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Caroline Frenkel

Jan Regulski

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Alix Lagasse

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Miya Väisänen

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Germán Clavijo

Stephen Doman

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Luca Casciato

Errika Horsley

Nancy Johnson

Cellos

David Cohen

Jennifer Brown

Noël Bradshaw

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Amanda Truelove

Peteris Sokolovskis

Double Basses

Rodrigo Moro Martin

Patrick Laurence

Matthew Gibson

Thomas Goodman

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Simo Väisänen

Flutes

Amy Yule

Patricia Moynihan

Piccolos

Sharon Williams

Rebecca Larsen

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Olivier Stankiewicz

Rosie Jenkins

Cor Anglais

Stéphane Suchanek

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bass Clarinet

Thomas Lessels

Soprano Saxophone

Kyle Horch

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Joost Bosdijk

Contra Bassoon

Dominic Morgan

Horns

Eirik Haaland

Clément Charpentier-Leroy

Annemarie Federle

David Sztankov

Fabian van de Geest

Trumpets

James Fountain

Kaitlin Wild

David Geoghegan

Trombones

Isobel Daws

Tom Berry

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Tom Edwards

Harp

Bryn Lewis

LSO String Experience Scheme

Established in 1992, the LSO String Experience Scheme enables young string players at the start of their professional careers to gain work experience by playing in rehearsals and concerts with the LSO. The musicians are treated as professional ‘extras’, and receive fees in line with LSO section players.

Supported by the Idlewild Trust, Thriplow Charitable Trust and Barbara Whatmore Charitable Trust.

Performing tonight are:

Silvestrs Kalniņš

Yat Hei Lee