LSO Half Six Fix

French Connections

Digital Concert Guide

THE CONCERT

The National Anthem of Great Britain will start the concert.

Hector Berlioz Overture: Le corsaire

Claude Debussy Fanfare and Le sommeil de Lear

from ‘Music to King Lear’

Tōru Takemitsu Fantasma/Cantos II

Maurice Ravel La valse

Sir Simon Rattle conductor & presenter

Peter Moore trombone

USING YOUR DIGITAL CONCERT GUIDE

- Navigate using the menu icon (≡) at the top of the screen.

If you're using this guide while enjoying the concert

- Connect to the Barbican Free WiFi network in the Concert Hall.

- Please set your phone to silent and don't use other apps during the music.

The London Symphony Orchestra is deeply saddened by the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Her Majesty had been the LSO’s Patron since her accession to the throne in 1952.

The Orchestra and Sir Simon Rattle will retain the programme for the concert in its original form, with the addition of the National Anthem.

Read our full tribute from the Orchestra further below in the programme

Welcome to tonight's Half Six Fix, a different way to experience the London Symphony Orchestra.

Introduction

Tonight’s concert celebrates the beauty and diversity of French orchestral music through works by three of France’s greatest composers. Hector Berlioz, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel were very different talents, but they shared a genius for writing for orchestra. This is brilliantly demonstrated in the works performed tonight: Berlioz’s swashbuckling concert overture Le corsaire, Debussy’s sensitive incidental music for Shakespeare’s King Lear, and Ravel’s elegant yet highly dramatic ‘dance-poem’ La valse. The concert also features a piece by Tōru Takemitsu, a Japanese master-orchestrator whose love of French music played a fundamental part in his creative development.

Programme notes by Kate Hopkins

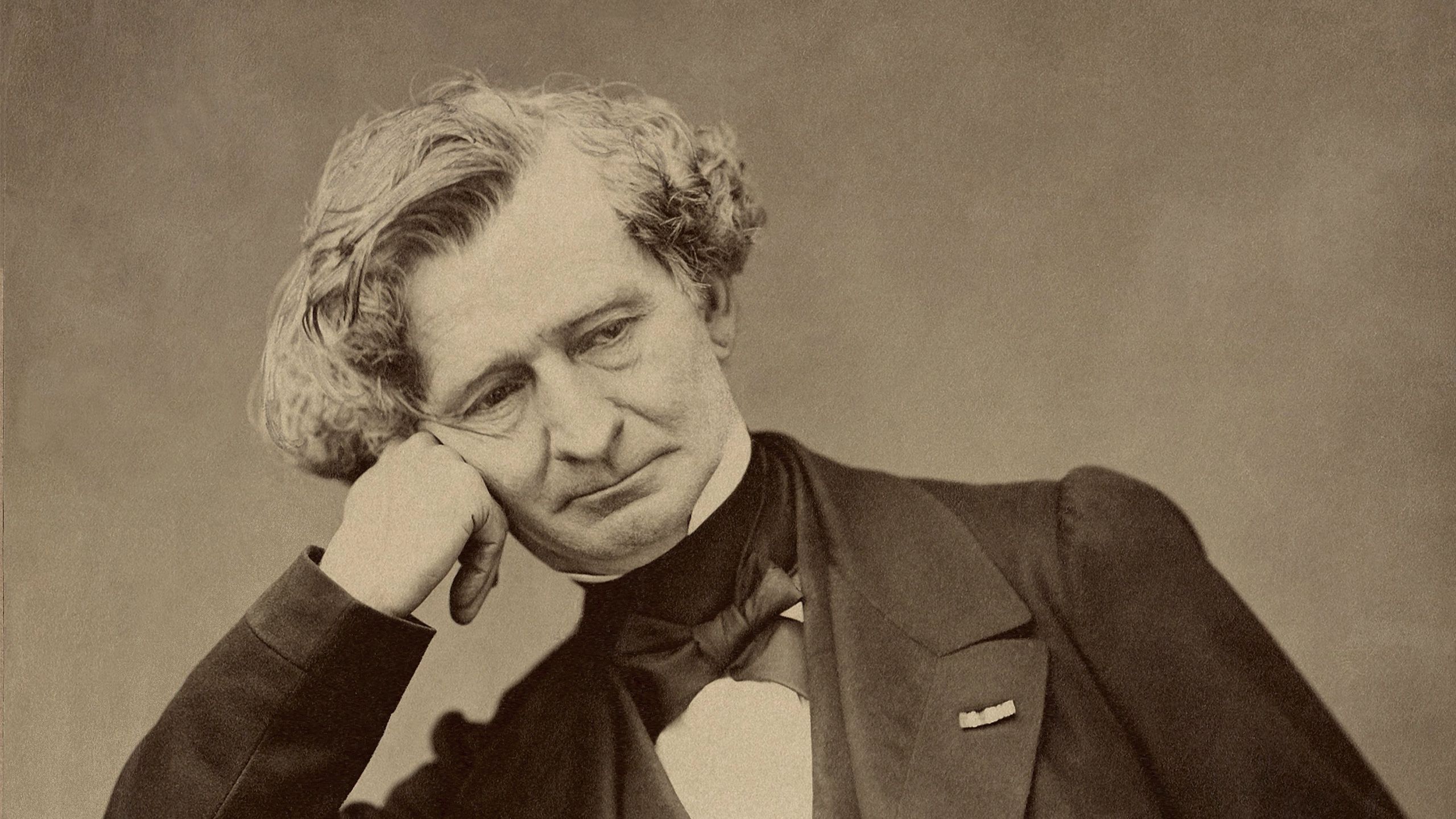

Hector Berlioz Overture: Le corsaire

✒️1852 | ⏰8 minutes

Spring and summer 1844 were busy periods for Hector Berlioz. In March he published his groundbreaking Treatise on Instrumentation and Orchestration, which would have a major influence on later composers including Richard Strauss and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. And in August he organised and conducted a massive concert as part of Paris’ Festival of Industry. By September he needed a holiday, and went to spend a month in Nice. He had loved this city since he’d written his King Lear overture there in 1831. His 1844 visit proved equally fruitful, resulting in a new concert overture, La tour de Nice (The Tower of Nice).

La tour de Nice’s premiere was not successful: one critic felt it filled the ‘imagination with strange and terrible images’. Undaunted, Berlioz set about revising the piece – and finding a more arresting title. Why he eventually settled on Le corsaire (The Corsair) is not known. He may have been inspired by stories of Nice’s historic corsairs: legalised pirates employed to attack the ships of France’s enemies. Or, as a bibliophile, he may have wanted to pay homage to Lord Byron’s poem The Corsair, which he had loved for over a decade. Either way, the work in its final form of 1852 brilliantly evokes the sea and a life of buccaneering adventure. It has become one of Berlioz’s most popular compositions.

Le corsaire is particularly notable for its imaginative orchestration, which ranges from delicate woodwind solos to forceful brass-dominated episodes. There are good tunes too, not least the gorgeous slow string melody that follows the attention-grabbing opening bars. A version of this lyrical theme also features in the overture’s exuberant, fast-paced main section, along with catchy new melodic material. Racing strings and sonorous brass end the piece in a mood of breathless excitement.

Who were the corsairs?

Corsairs were privateers: individuals (not part of an official naval force) who engaged in maritime warfare under a commission. Corsairs were particularly prevalent in North Africa and in pre-Revolutionary France, where they were employed by the French King to attack the ships of France’s enemies. In the 19th century corsairs were considered romantic figures, as Charlotte Bronte observed in Jane Eyre. Lord Byron’s 1814 poem The Corsair was immensely popular throughout Europe and inspired musical works including Verdi’s 1848 opera Il corsaro.

Claude Debussy Fanfare and Le sommeil de Lear from ‘Music to King Lear’

✒️1904 | ⏰5 minutes

Theatre was a lifelong passion for Claude Debussy. He followed contemporary developments with interest, befriended many writers and wrote the libretto for his own unfinished opera La chute de la maison Usher (The Fall of the House of Usher). He also attempted collaborations with several playwrights and actors, but only one project came to full fruition – incidental music for Le martyre de Saint Sébastien by the eccentric Italian dramatist Gabriele d’Annunzio.

His incidental music for King Lear was intended to consist of seven musical interludes accompanying a new production of Shakespeare’s play in Paris. It was commissioned in 1904 by the actor-impresario André Antoine. The composer, who had toyed with writing operas based on the Bard’s Hamlet and As You Like it, was initially enthusiastic. However, his passionate love affair with the singer Emma Bardac distracted him from his work, and he found Antoine increasingly difficult to deal with. Things came to a head when the impresario refused to provide him with the ensemble of 30 musicians he had demanded. Declaring that a smaller group would only make ‘a pathetic little sound like fleas rubbing their legs together’, Debussy quit.

The two numbers that he did complete reveal that the King Lear project as a whole might have been extremely powerful. The opening ‘Fanfare’ is scored for brass, timpani and harp, and contrasts assertive and regal outer sections with a more meditative central episode. The music has a cinematic grandeur that anticipates William Walton’s film scores for Laurence Olivier’s Henry V and Richard III. The very different ‘Le sommeil de Lear’ (The Sleep of Lear) was intended to precede Lear’s reunion with Cordelia in Act IV. Hushed dynamics, shifting harmonies, muted strings and falling phrases in horns and woodwind vividly depict Lear’s uneasy slumber in a sombre twilit landscape.

Incidental Music for Shakespeare

Debussy’s King Lear project may have ended in disaster, but other composers had happier experiences with Shakespearean incidental music. In 1913 Ralph Vaughan Williams spent a busy period in Stratford-upon-Avon writing music for several of the Bard’s plays, including The Merry Wives of Windsor. Jean Sibelius created a haunting score (1925–6) for a production of The Tempest at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen and the Finnish National Theatre. Dmitri Shostakovich wrote extensive incidental music for both Hamlet (1931–2) and King Lear (1940). Most successful, perhaps, was Felix Mendelssohn, whose sparkling score for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1842) remains much loved to this day.

Tōru Takemitsu Fantasma/Cantos II

✒️1994 | ⏰16 minutes

From the 1970s onwards, Tōru Takemitsu became increasingly fascinated by traditional Japanese gardens. He perceived similarities between their construction and that of his compositions, writing ‘my music is like a garden, and I am the gardener. Listening to my music can be compared with walking through a garden and experiencing the changes in light, pattern and texture’. Fantasma/Cantos II (1994) is the last in a series of horticultural orchestral works that also include In an Autumn Garden (1973), A Flock Descends Into the Pentagonal Garden (1977), Spirit Garden (1994) and Fantasma/Cantos for clarinet and orchestra (1991).

Fantasma/Cantos II is scored for solo trombone and orchestra. Takemitsu achieves a remarkable range of orchestral colours through a generous percussion section – including vibraphone, glockenspiel, celeste and tubular bells – and a woodwind section that features alto flute, bass clarinet and cor anglais. The absence of brass instruments gives the orchestral writing an especial delicacy, while the song-like trombone part reveals that this forceful instrument can also sound tender and lyrical. The subtle orchestral writing and rich harmonies recall Debussy and Ravel – but there is also a playful hint of jazz in the trombone part, not least in the massive glissando that marks the piece’s halfway point.

However, the piece’s greatest inspiration are the Japanese gardens of the Edo period (1603–1867): large strolling gardens containing ponds, islands and artificial hills, which can be enjoyed from various viewpoints along a circular trail. Takemitsu captures their effect through a simple musical idea which is repeated many times, gradually changing and evolving with each statement. In the composer’s own words: ‘You walk along the path, stopping here and there to contemplate, and eventually find yourself back where you started from. Yet it is no longer the same starting point.’

A Personal Connection

Sir Simon Rattle has a long-term association with his late friend Tōru Takemitsu’s music. He conducted the world premieres of the composer’s Vers, l’arc-en-ciel, Palma (1984) and My Way of Life (1990) with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and the world premiere of his piano concerto Riverrun (1985) with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the composer’s close friend Peter Serkin. He also gave the Proms premiere (1987) of A Flock Descends Into the Pentagonal Garden and the UK premieres in 1989 and 1990 of Gémeaux and Visions, and conducted the composer’s guitar concerto To the Edge of Dream on a recording for EMI.

Maurice Ravel La valse

✒️1920 | ⏰13 minutes

Dance was one of Maurice Ravel’s great inspirations. In 1906 he wrote to his friend Jean Marnold of his especial affinity with the Viennese waltz, its ‘wonderful rhythms’ and ‘joie de vivre’. To both Marnold and another friend he declared his intention to write an orchestral homage to Vienna’s ‘waltz-king’ Johann Strauss II, entitled Wien (Vienna). However, he soon became distracted by other projects. Then came World War I, during which his duties as an ambulance driver and subsequent illness left him little time for composition. It was only in 1919 that a commission from Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes led him to return to his 1906 project, now re-named La valse.

By this time, Vienna’s waltzes were no longer associated with liberated joie de vivre, but with decadence, inflated national pride and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Ravel claimed in 1922 that La valse merely depicted the waltz’s potential for ‘hallucinatory ecstasy’ and that it had nothing to do with the ‘present situation in Vienna’. However, the piece’s increasingly uneasy air and the frequent appearance of the tritone – a musical interval known as ‘the devil in music’ – may suggest otherwise.

La valse’s mysterious opening depicts dancing couples dimly glimpsed through clouds. A melodious series of waltz themes follow. These feature a remarkable variety of orchestral colours and textures, and include quotations from Ravel’s own Valses nobles et sentimentales (1911). In the piece’s later stages, the waltz themes gradually fragment and disintegrate, and the music grows increasingly loud and wild, eventually building to a cataclysmic conclusion.

Diaghilev admired Ravel’s score but rejected it as unsuitable for dancing. La valse was first heard in concert form in Paris on 12 December 1920. Although it has been staged by famous choreographers including George Balanchine and Frederick Ashton, it remains best known as a concert work.

Spirit of the Dance

Ravel’s orchestral music teems with dance rhythms. Valses nobles et sentimentales (1911) offers a more upbeat homage to the waltz than the later La valse. Rapsodie espagnole (1907–8) features the Malaguena – a folk dance from Malaga – and the languid Cuban-inspired Habanera. Le tombeau de Couperin (1914–17 piano version; 1919 orchestral version) pays homage to traditional French dances such as the Menuet and the Rigaudon. And in 1928 the composer paid a final tribute to Spanish dance forms in the lively, insistent Boléro, now one of his most popular works.

Our Tribute to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

The London Symphony Orchestra is deeply saddened by the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Her Majesty had been the LSO’s Patron since her accession to the throne in 1952, continuing a long association of the Sovereign with the Orchestra and its players, stretching back to its formation in 1904.

The Orchestra is privileged to have hosted Her Majesty at many of its concerts and events – from opening the Barbican Centre in 1982, to hosting a gala at Buckingham Palace in 2015. The Queen was present at some of the most significant moments in our history and was a loyal and committed supporter of the orchestra throughout her reign.

The London Symphony Orchestra sends its condolences to the Royal Family at this sad time and joins the nation in mourning our much-loved monarch.

The Performers

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

Sir Simon Rattle was born in Liverpool and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1980 to 1998, he was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. In 2002 he took up the position of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, where he remained until the end of the 2017/18 season.

Sir Simon became Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017, and will become Conductor Emeritus from the 2023/24 season. He will then take up the position of Chief Conductor of the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks in Munich. He is a Principal Artist of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and Founding Patron of Birmingham Contemporary Music Group.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble.

Sir Simon Rattle was knighted in 1994. In the New Year’s Honours of 2014 he received the Order of Merit from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. In 2019, he was given Freedom of the City of London.

Peter Moore

Trombone

'Moore displays an eloquence and nobility that one might have thought impossible except by the human voice' (BBC Music Magazine upon showcasing his debut album Life Force).

Peter Moore astounds international audiences with expression directly from the soul and masterful technique, complimented by his boundless versatility and instant personal connection. He has leapt from rising star to become one of the key exponents of his instrument.

Peter has given recitals at venues including the Vienna Musikverein, Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, Cologne Philharmonie, Tonhalle Zürich and the Barbican Centre. He has undertaken tours across China, Japan, Korea, Australasia and South America, exhibiting a wide range of repertoire from early Baroque music to Romantic Lieder transcriptions, whilst introducing new audiences to original trombone works. In August 2022 he made his debut at the BBC Proms performing George Walker’s Trombone Concerto.

As a soloist, Peter has appeared with the London Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC NOW, BBC Concert Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, Ulster Orchestra, Lucerne Symphony and Polish Chamber Orchestra. He is featured frequently on BBC Radio 3 and was a New Generation Artist between 2015 and 2017. He has given multiple performances at Wigmore Hall. World premieres by Francisco Coll, Roxanna Panufnik, Dani Howard, and the UK premiere of James Macmillan’s Trombone Concerto signify Peter’s desire to bring the trombone to the forefront of contemporary music.

Peter came to national attention in 2008 at the age of twelve when he became the youngest ever winner of the BBC Young Musician competition. He is the Principal Trombone of the London Symphony Orchestra and alongside his performing career, he is Professor of Trombone at the Royal Academy of Music.

Peter Moore is a Getzen International Artist and performs on the 4147IB trombone

Listen to Peter Moore talk more about Fantasma/Cantos II

London Symphony Orchestra

At the London Symphony Orchestra we strive to inspire hearts and minds through world-leading music-making. We were established in 1904, as one of the first orchestras shaped by its musicians.

Through inspiring music, a world-leading learning and community programme and technological innovations, our reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

On Stage

Guest Leader

Andrej Power

First Violins

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Claire Parfitt

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Rhys Watkins

Caroline Frenkel

Lulu Fuller

Hilary Jane Parker

Angela Wee

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Alix Lagasse

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Csilla Pogany

Paul Robson

Dunja Bontek

Patrycja Mynarska

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Steve Doman

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Thomas Beer

Michelle Bruil

Luca Casciato

Mizuho Ueyama

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Alastair Blayden

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Amanda Truelove

Salvador Bolón

Judith Fleet

Peteris Sokolovskis

Joanna Twaddle

Double Basses

Rodrigo Moro Martin

Patrick Laurence

Matthew Gibson

Thomas Goodman

Joe Melvin

José Moreira

Jani Pensola

Simo Väisänen

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Amy Yule

Imogen Royce

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboe

Juliana Koch

Olivier Stankiewicz

Henrietta Cooke

Cor Anglais

Clément Noël

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Filippo Biuso

Chi-Yu Mo

Bass Clarinet

Katy Ayling

Bassoon

Rachel Gough

Daniel Jemison

Joost Bosdijk

Contra Bassoon

Martin Field

Horns

Timothy Jones

Ben Hulme

Angela Barnes

Kristina Yumerska

Jonathan Maloney

Trumpets

James Fountain

Christopher Hart

Kaitlin Wild

Niall Keatley

Trombone

Peter Moore

Simon Johnson

Tom Berry

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Rachel Gledhill

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Tom Edwards

Rachel Gledhill

Jeremy Cornes

Oliver Yates

Harp

Bryn Lewis

Helen Tunstall

Piano

Elizabeth Burley