Daphnis and Chloé

Maurice Ravel

✒️ 1909–1912 | ⏰ 70 minutes

What's the background?

Ravel was 34 when, in 1909, the impresario and founder of the Ballets Russes, Serge Diaghilev, commissioned him to write a ballet for his company’s 1910 Paris season. Ravel struggled with the work and missed his deadline. The gap was filled by Stravinsky’s The Firebird – and it’s amazing to think that this major Stravinsky work (which soon led to two more ballets for Diaghilev: Petrushka and The Rite of Spring) wouldn’t exist had it not been for Ravel dragging his heels.

Many complications hounded Daphnis and Chloé, not least the rehearsal process, hampered, as Ravel noted, by the fact that the Russian choreographer, Mikhail Fokine, didn’t know ‘a word of French, and I only know how to swear in Russian’. Fokine was more interested in the idea of the physicality of ancient pagan dance, while Ravel was concerned instead with ‘the Greece of my dreams, which is similar to that imagined and painted by French artists at the end of the 18th century’.

‘I felt that the music would be unusual, colourful and, most important … totally unlike any other ballet music.’

Why is this piece so iconic?

Fokine wanted Daphnis and Chloé to run continuously, instead of being structured in separate numbered movements. As a result, there’s a dramatic sweep across the entire work, arranged in three parts. At around 55 minutes, this is one of the longest ballets. Ravel scored the piece for a huge orchestra – one reason why Daphnis and Chloé is rarely mounted in its original ballet form. It’s expensive to put on, and the orchestra pits of many theatres aren’t big enough. To this already expansive scoring, Ravel audaciously extended the orchestra’s tonal palette by adding in an optional wordless chorus. This is often cut, even in concert performances, but tonight’s Half Six Fix offers a chance to hear how seamlessly Ravel integrated the chorus into the overall soundscape.

What is the music like?

The scenario, set on the Greek island of Lesbos, revolves around the romance of the goatherd Daphnis and the shepherdess Chloé, and was adapted by Fokine from a novel by the second-century Greek writer Longus. Ravel may have rejected Fokine’s request for physical, pagan music but there is no shortage of sensuality and even unbridled ecstasy. He created a keen impression of a pastoral idyll and a hint of the ancient world, even if filtered through a more modern, romanticising lens.

Ravel also excelled in set pieces, such as, in Part One, the ‘Grotesque Dance’ of the cowherd Dorcon (a rival for Chloé’s affections) followed by ‘Daphnis’ Light and Graceful Dance’, and Lyceion’s attempt to seduce Daphnis. Part Two features the violent ‘War Dance’ of the pirates, who abduct Chloé. Part Three opens with gently rippling flutes and clarinets, the sounds of nature awakening at daybreak and one of the most radiant, extended and scintillatingly orchestrated sunrises in music. There is a magical central Pantomime of thanksgiving enacted by Daphnis and Chloé before the god Pan, after they are reunited through his intervention. And the ballet ends with a dizzying, rhythmically propulsive and increasingly ecstatic ‘General Dance’.

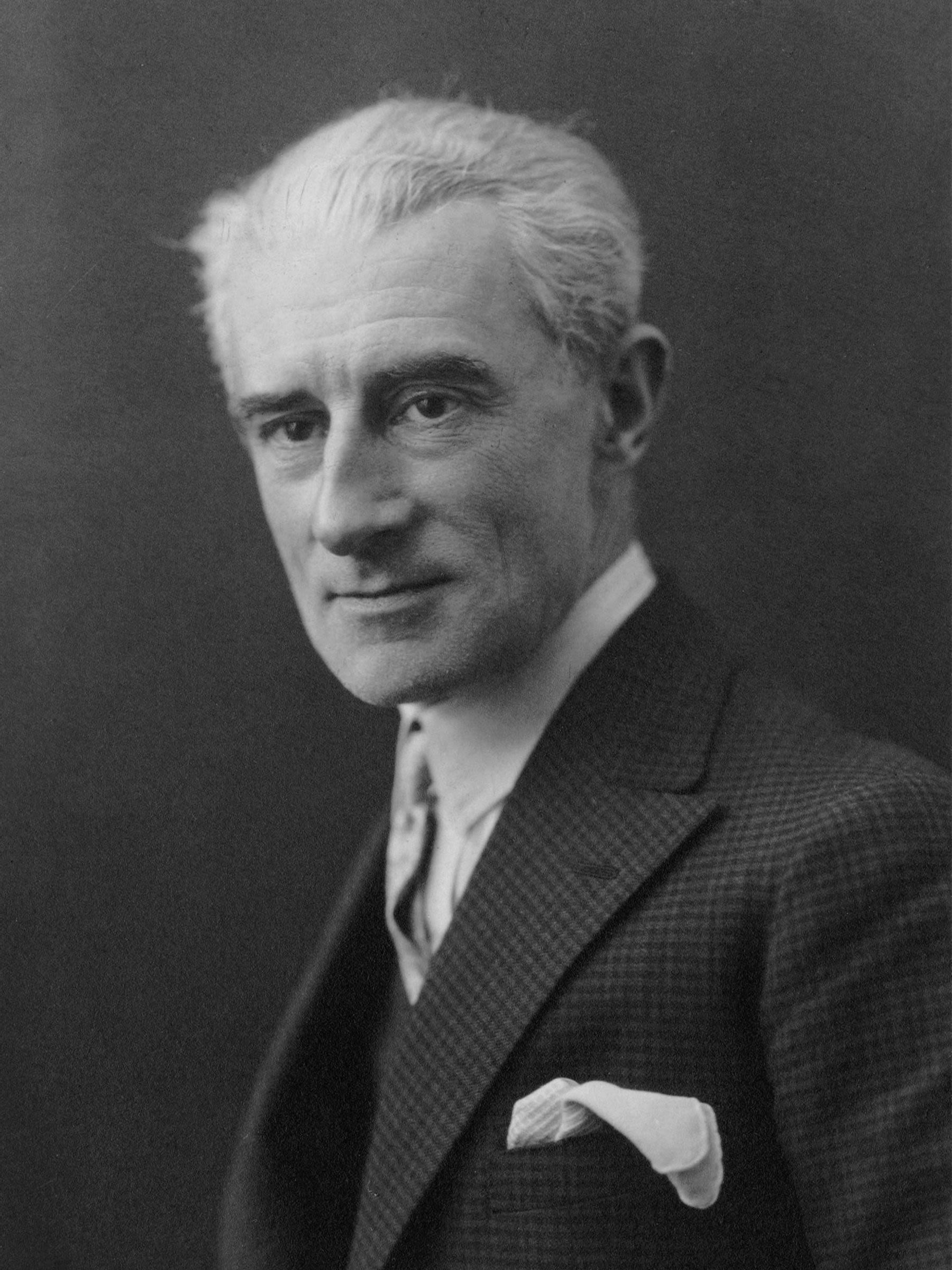

Maurice Ravel

Born: Ciboure, France, 1875

Died: Paris, France, 1937

‘I still have so much music in my head, I’ve said nothing, I still have so much to say … ’

Igor Stravinsky referred to him as ‘the Swiss clockmaker’ for his craftsman-like attention to detail, and it’s no accident that Maurice Ravel had a fondness for mechanical toys and miniatures. His fascination with childhood innocence coloured a number of works, including the ballet Mother Goose and the opera L’enfant et les sortilèges (The Child and the Spells). He looked to the French 17th-century keyboardists in Le tombeau de Couperin, to the East in the song-cycle Shéhérazade and to American jazz in his Piano Concerto in G. The sounds of Spain suffuse his Rapsodie espagnole and Alborada del gracioso, not to mention his most popular piece, Boléro. This was his ‘one masterpiece’, he said, before adding: ‘Unfortunately, there’s no music in it’. He was famously self-deprecating too.

Ravel studied at the Paris Conservatoire, and controversially failed to win the prestigious Prix de Rome. Yet by the time of his ‘final failure’, in 1905, he had written key works such as the solo piano Jeux d’eau (1901) and the String Quartet (1902–03). He served as a driver in World War I, and returned just before the death of his mother, which broke down all close human contact for the reclusive composer. He wrote little after his two piano concertos (1929–31). He experienced neurological deterioration for the last decade of his life, which worsened after a car accident in 1932. He died in December 1937.

Keep Listening

Delve deeper into the music featured in our Half Six Fix series, and find related music recommendations, with our Half Six Fix playlist.

Sir Antonio Pappano

Chief Conductor Designate

After 22 years as Music Director of the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, Sir Antonio Pappano is LSO Chief Conductor Designate, becoming Chief Conductor this September. He was born just 20 miles away, in Epping, and moved to the US aged 13, but now lives in London. He has also held lead positions with the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels (1992–2002) and the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome (2005–23). Opera is in his blood, and he brings this love of dramatic narrative and storytelling to his orchestral performances too. He directs his players with great immediacy: his conducting style is unfiltered, impassioned and straight from the heart. A natural communicator about music, too, he has presented programmes for BBC TV. This year he was appointed Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, having conducted at the Coronation of HRH King Charles III last year.

Tenebrae

Described as ‘phenomenal’ (The Times) and ‘devastatingly beautiful’ (Gramophone magazine), award-winning choir Tenebrae is one of the world’s leading vocal ensembles, renowned for its passion and precision.

On Stage

Sopranos

Jennifer Clark

Elizabeth Drury

Fiona Fraser

Isabella Gibber

Catriona Holsgrove

Marie Macklin

Laura Newey

Elisabeth Partridge

Áine Smith

Rosanna Wicks

Altos

Amy Blythe

Eleanor Minney

Sophie Overin

Lorna Price

Shivani Rattan

Anna Semple

Olivia Shotton

Joy Sutcliffe

Tenors

James Beddoe

Jeremy Budd

Jacob Ewens

Jack Granby

Jack Harberd

Sam Madden

Carlos Otero

Dominic Wallis

Ed Woodhouse

Basses

Gregory Bannan

Tom Butler

Joseph Edwards

Simon Grant

Thomas Lowen

James Mawson

Gavin Moralee

Binath Philomin

Jonathan Pratt

The London Symphony Orchestra

At the London Symphony Orchestra, we strive to inspire hearts and minds through world-leading music-making. We were established in 1904 as one of the first orchestras shaped by its musicians, and today we’re ranked among the world’s top orchestras. As Resident Orchestra at the Barbican since the Centre opened in 1982, we perform some 70 concerts here every year. We also perform over 50 concerts a year to audiences throughout the UK and worldwide, and deliver a far-reaching programme of recordings, live-streams and on-demand broadcasts.

Through our world-leading learning and community programme, LSO Discovery, we’re connecting people from all walks of life to the power of great music. Our musicians are at the heart of this unique programme. In 1999, we formed our own recording label, LSO Live, which has become one of the world’s most talked-about classical labels. As a leading orchestra for film, we’ve entertained millions with classic scores for Star Wars, Indiana Jones and many more.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Noé Inui

Ginette Decuyper

Maxine Kwok

Laura Dixon

William Melvin

Stefano Mengoli

Claire Parfitt

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Richard Blayden

Dániel Mészöly

Shoshanah Sievers

Rhys Watkins

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Alix Lagasse

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Csilla Pogány

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Ricky Gore

Violas

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Matan Gilitchensky

Steve Doman

Thomas Beer

Germán Clavijo

Julia O’Riordan

Robert Turner

Mizuho Ueyama

May Dolan

Vanessa Hristova *

Shiry Rashkovsky

Martin Schaefer

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Laure Le Dantec

Alastair Blayden

Ève-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Amanda Truelove

Judith Fleet

Ghislaine McMullin

Peteris Sokolovskis

Joanna Twaddle

Double Basses

Rodrigo Moro Martín

Patrick Laurence

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Chaemun Im

Thomas Goodman

Ben Griffiths

Adam Wynter

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Imogen Royce

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Alto Flute

Patricia Moynihan

Oboes

Olivier Stankiewicz

Rosie Jenkins

Cor Anglais

Augustin Gorisse

Clarinets

Sérgio Pires

James Gilbert

Bass Clarinet

Martino Moruzzi

E flat Clarinet

Chi-Yu Mo

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Joost Bosdijk

Contra Bassoon

Martin Field

Horns

Timothy Jones

Diego Incertis Sánchez

Angela Barnes

James Pillai

Jonathan Maloney

Off stage Horn

Brendan Thomas

Trumpets

James Fountain

Imogen Whitehead

Adam Wright

Kaitlin Wild

Off stage Trumpet

Jon Holland

Trombones

Simon Johnson

Jonathan Hollick

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Tom Edwards

* Members of the LSO String Experience Scheme

Established in 1992, the Scheme enables young string players at the start of their professional careers to gain work experience by playing in rehearsals and concerts with the LSO. The musicians are treated as professional ‘extras’, and receive fees in line with LSO section players. Kindly supported by the Barbara Whatmore Charitable Trust, the Idlewild Trust and The Thriplow Charitable Trust.

Programme Notes Edward Bhesania. Edward Bhesania is a music journalist and editor who writes for The Stage, The Strad and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama.

LSO Visual Identity & Concept Design Bridge & Partners