Symphony No 5

Ralph Vaughan Williams

✒️1938–43, revised 1951 | ⏰ 35 minutes

What's the background?

With the premiere of his Fourth Symphony in 1935, Vaughan Williams shocked his listeners. He was admired for pieces that reflected England’s countryside and folk music – like his Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis and The Lark Ascending. But the Fourth Symphony possessed a violent, eruptive force, and was later interpreted to be a premonition of the impending World War II. (Vaughan Williams himself denied this, saying he just wrote what he wanted to.)

Likewise, when the Fifth Symphony was first heard – in 1943, amid the War – its contemplative, spiritual quality came as another surprise. What had happened to the progressive Vaughan Williams of the Fourth Symphony? The Fifth was again seen to be a look ahead, but now towards peacetime.

‘All great music has the element of popular appeal. It must penetrate beyond the walls of the studio into the world outside.’

Why is this piece so iconic?

In 1943, the Fifth Symphony was thought to be the final reflections of a composer now in his 70s. It turned out instead to be the mid-point in Vaughan Williams’ symphonic journey, which would continue with four more symphonies over the next 15 years.

The conductor Sir Adrian Boult wrote that the Fifth Symphony’s ‘serene loveliness is completely satisfying in these times and shows, as only music can, what we must work for when this madness is over’. The composer’s muse Ursula Wood (later to be his second wife) remembered that ‘the music seemed to bring the peace and blessing for which [people] longed’. The first US performance in New York split the critics, however. The New York Times’ Olin Downes saw the Symphony as proof of the composer’s ‘unique and very personal genius’, while the Herald Tribune’s reviewer dismissed it as ‘anti-intellectual’ and ‘not of this century’.

What is the music like?

Distant horns open the first movement, with violins unfolding a strangely archaic-sounding melody. This leads to a more unsettled section, the string instruments dispersing in different directions while a slightly disconcerting falling three-note motif rolls around the wind instruments. The horn calls later return, seemingly restoring calm, but soon there’s a swell of passionate, resplendent radiance. The horns return once more, this time receding into the distance.

The second movement is a Scherzo (a light-hearted, playful piece) that trips along with various circling ideas, occasionally punctured by a rude, Eastern-sounding interjection from oboe and cor anglais. Amid the rhythmic interplay, a sustained hymn-like tune emerges in the trombones. But the scherzo music returns, pithy and precise, only to vanish suddenly at the end in a puff of smoke.

The third movement Romance is the heart of the Symphony. This is classic Vaughan Williams, with expansive melodies and enveloping warmth, though it’s not without drama. The return of the opening music allows a final surge of string-writing, but the end is of hushed repose.

The last movement is labelled a ‘Passacaglia’, in which a harmonic or melodic pattern becomes the basis for a sequence of variations – after which Vaughan Williams brings back the horn calls from the first movement. The closing music floats upwards as if sung by an ethereal choir of angels.

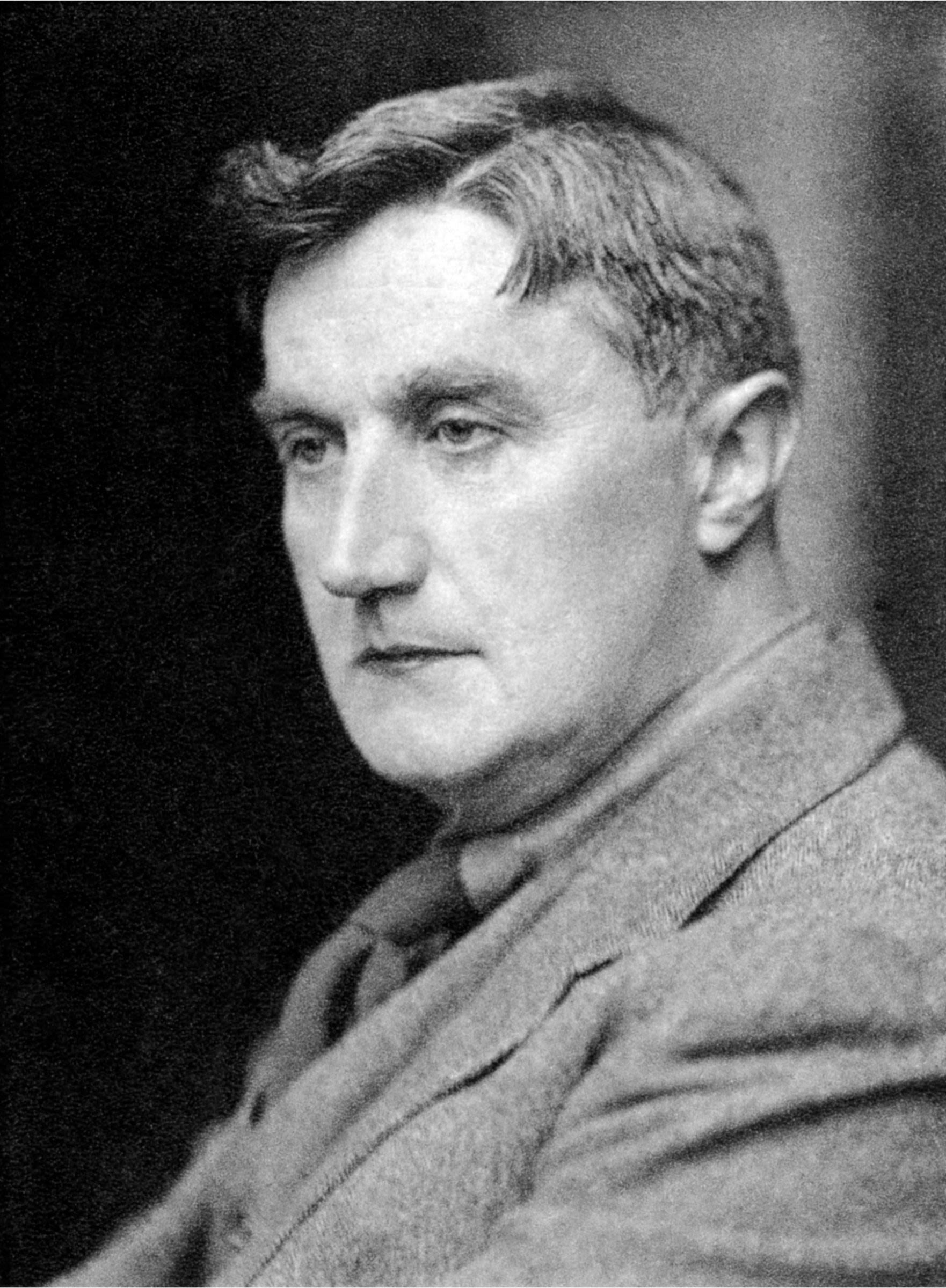

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Born: : Gloucestershire, UK, 1872

Died: London, UK, 1958

‘The art of music … is the expression of the soul of a nation – any community of people who are spiritually bound together.

Ralph Vaughan Williams was a major figure in the reflowering of English music in the early 20th century – along with Edward Elgar, Gustav Holst and Frederick Delius – and helped to dispel England’s reputation as ‘The Land Without Music’.

He was born in Gloucester, his father a vicar and his mother a relative both of Josiah Wedgwood (the pottery designer) and biologist Charles Darwin. He studied at London’s Royal College of Music, where he became close friends with Holst. In the first years of the 1900s he began his work collecting folk songs (over 800 in all) and became interested in Elizabethan music – both these activities influenced his own music. He also edited the hymn collection The English Hymnal. With a keen social conscience, he lied about his age in order to serve in World War I, during which he lost many friends, including the young composer George Butterworth.

His choral works include Toward the Unknown Region and the Five Mystical Songs. His setting of William Shakespeare’s Serenade to Music also remains popular. He wrote nine symphonies, four operas and several works for solo instrument with orchestra – including, more unusually, for tuba and harmonica. The soaring, folk-song-coloured The Lark Ascending for violin and orchestra, and the haunting Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis for double string orchestra, remain his most popular works, seen as emblematic of British music of this period. After the death of his first wife in 1951, he remarried aged 80, reviving his zest for life.

Keep Listening

Delve deeper into the music featured in our Half Six Fix series, and find related music recommendations, with our Half Six Fix playlist.

Sir Antonio Pappano

Chief Conductor Designate

After 22 years as Music Director of the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, Sir Antonio Pappano became LSO Chief Conductor Designate this season, and becomes Chief Conductor in September. He was born just 20 miles away, in Epping, and moved to the US aged 13, but now lives in London. He has also held lead positions with the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels (1992–2002) and the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome (2005–23). Opera is in his blood, and he brings this love of dramatic narrative and storytelling to his orchestral performances too. He directs his players with great immediacy: his conducting style is impassioned and straight from the heart. A natural communicator about music, too, he has presented programmes for BBC TV. This year he was appointed Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, having conducted at the Coronation of HRH King Charles III last year.

The London Symphony Orchestra

At the London Symphony Orchestra, we strive to inspire hearts and minds through world-leading music-making. We were established in 1904 as one of the first orchestras shaped by its musicians, and today we’re ranked among the world’s top orchestras. As Resident Orchestra at the Barbican since the Centre opened in 1982, we perform some 70 concerts here every year. We also perform over 50 concerts a year to audiences throughout the UK and worldwide, and deliver a far-reaching programme of recordings, live-streams and on-demand broadcasts. Through our world-leading learning and community programme, LSO Discovery, we’re connecting people from all walks of life to the power of great music. Our musicians are at the heart of this unique programme. In 1999 we formed our own recording label, LSO Live, which has become one of the world’s most talked-about classical labels. As a leading orchestra for film, we’ve entertained millions with classic scores for Star Wars, Indiana Jones and many more.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Noé Inui

Ginette Decuyper

Maxine Kwok

Stefano Mengoli

Claire Parfitt

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Julian Azkoul

Richard Blayden

Dániel Mészöly

Djumash Poulsen

Shoshanah Sievers

Rhys Watkins

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Alix Lagasse

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Csilla Pogány

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Caroline Frenkel

Ricky Gore

Violas

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Matan Gilitchensky

Steve Doman

Thomas Beer

Robert Turner

Mizuho Ueyama

May Dolan

Shiry Rashkovsky

Alistair Scahill

Martin Schaefer

David Vainsot

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Alastair Blayden

Ève-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Amanda Truelove

Judith Fleet

Ghislaine McMullin

Desmond Neysmith

Kosta Popovic *

Peteris Sokolovskis

Joanna Twaddle

Double Basses

Rodrigo Moro Martín

Patrick Laurence

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Chaemun Im

Ben Griffiths

Evangeline Tang

Adam Wynter

Flutes

Julien Beaudiment

Chloé Dufossez

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboe

Juliana Koch

Cor Anglais

Augustin Gorisse

Clarinets

Sérgio Pires

Martino Moruzzi

Bassoons

Daniel Jemison

Joost Bosdijk

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Trumpets

James Fountain

Adam Wright

Trombones

Simon Johnson

Jonathan Hollick

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Timpani

Patrick King

* Members of the LSO String Experience Scheme

Established in 1992, the Scheme enables young string players at the start of their professional careers to gain work experience by playing in rehearsals and concerts with the LSO. The musicians are treated as professional ‘extras’, and receive fees in line with LSO section players. Kindly supported by the Barbara Whatmore Charitable Trust, the Idlewild Trust and The Thriplow Charitable Trust.

Programme Notes Edward Bhesania.

Edward Bhesania is a music journalist and editor who writes for The Stage, The Strad and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama.

LSO Visual Identity & Concept Design Bridge & Partners