Je ne suis pas une fable à conter

Golfam Khayam

✒️2023 | ⏰ 10 minutes

Golfam Khayam

Born: 1982

No one was more surprised about the birth of this piece than the composer herself. When Iranian-born composer and improviser Golfam Khayam saw a video of Barbara Hannigan participating in an event supporting Persian culture, she felt compelled to get in touch. Hannigan replied within two hours, and within months this new work was born.

Je ne suis pas une fable à conter (I am not a tale to be told) is based on a poem written in 1955 by celebrated Iranian poet, and family friend, Ahmad Shamlou, whose works Khayam describes as ‘beyond time and space’. Khayam grew up with Shamlou’s poems and sees this one as being ‘the narrator for so many silent voices seeking light through dark times’.

The piece is shaped for the particular – perhaps unique – talents of Hannigan, who both sings (in Farsi and French) and conducts. Elements of it – melodic shape, ornamentation, the use of non-Western scales and drones (long held notes) – are borrowed from Persian music, and the orchestral parts include patterns or phrases that the performers are free to play in an improvised way, creating what Khayam has likened to a ‘Persian carpet’ beneath the vocal lines. As Hannigan has said, no two performances are the same. She has also noted – perhaps reflecting Khayam’s view of the poem as empowering unheard voices – that the orchestral players, in their musical choices, can also choose not to play, ‘to let silence be your voice’.

Je ne suis pas une fable à conter

Text & Translation

Text

Je ne suis pas une fable à conter

Pas une chanson à chanter

Pas une voix à écouter

Ni quelque chose qu’on peut voir

Ou quelque chose à savoir

L’arbre parle à la forêt

L’étoile parle aux cieux

Et moi, c’est à toi que je parle

Dans le plus sombre

des cimetières

Pour les morts de cette année

Je ne suis pas une fable à conter

Pas une chanson à chanter

L’étoile parle aux cieux

Et moi, c’est à toi que je parle

Farsi phrases used in the text

Ghéséh nistam ké bégooyee

Man dardé moshtarékam,

marA faryAd kon

Translation

I am not a tale to be told

Not a song to be sung

Not a sound to be heard

Or something that you can see

Or something that you can know

Tree speaks to the wood

Star to the sky

And I speak to you

In the darkest of graveyards

For the dead of this year

I am not a tale to be told

Not a song to be sung

Star to the sky

And I speak to you

Translation

I’m not a tale to be told

I’m a shared pain, cry me out

Excerpts from Symphony No 39 in G minor

Joseph Haydn

✒️1765 | ⏰ 16 minutes

Joseph Haydn

Born: 1732

Died: 1809

In 1761, at the age of 29, Joseph Haydn became Vice-Kapellmeister (effectively second in charge of music) at the court of the Esterházy family. He later rose to Kapellmeister and stayed in the family’s employment for nearly 30 years in all. The price he paid for his loyalty was isolation from musical trends elsewhere. On the flipside, as he famously said, he was ‘forced to become original’.

Most of Haydn’s 107 symphonies, especially at this time, were written for performances at court – high-class entertainment – so No 39 is unusual in being written in a minor key (rather than a more sunny major key). This symphony falls into the period of his so-called Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) period, referring to a style borrowed from the literary movement that highlighted more turbulent and passionate moods. One expert has described these symphonies as ‘longer, more passionate and more daring’ than what came before.

Until relatively recently, Haydn’s symphonies were overshadowed by those of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and their many successors into the Romantic period and beyond. Sir Simon Rattle, the LSO’s Conductor Emeritus, has gone as far as declaring that Haydn would be the one composer he couldn’t live without. And Barbara Hannigan has said of Haydn’s symphonies: ‘Once I started conducting the symphonies … I realised they’re like operas – so theatrical.’

The Miraculous Mandarin – Suite

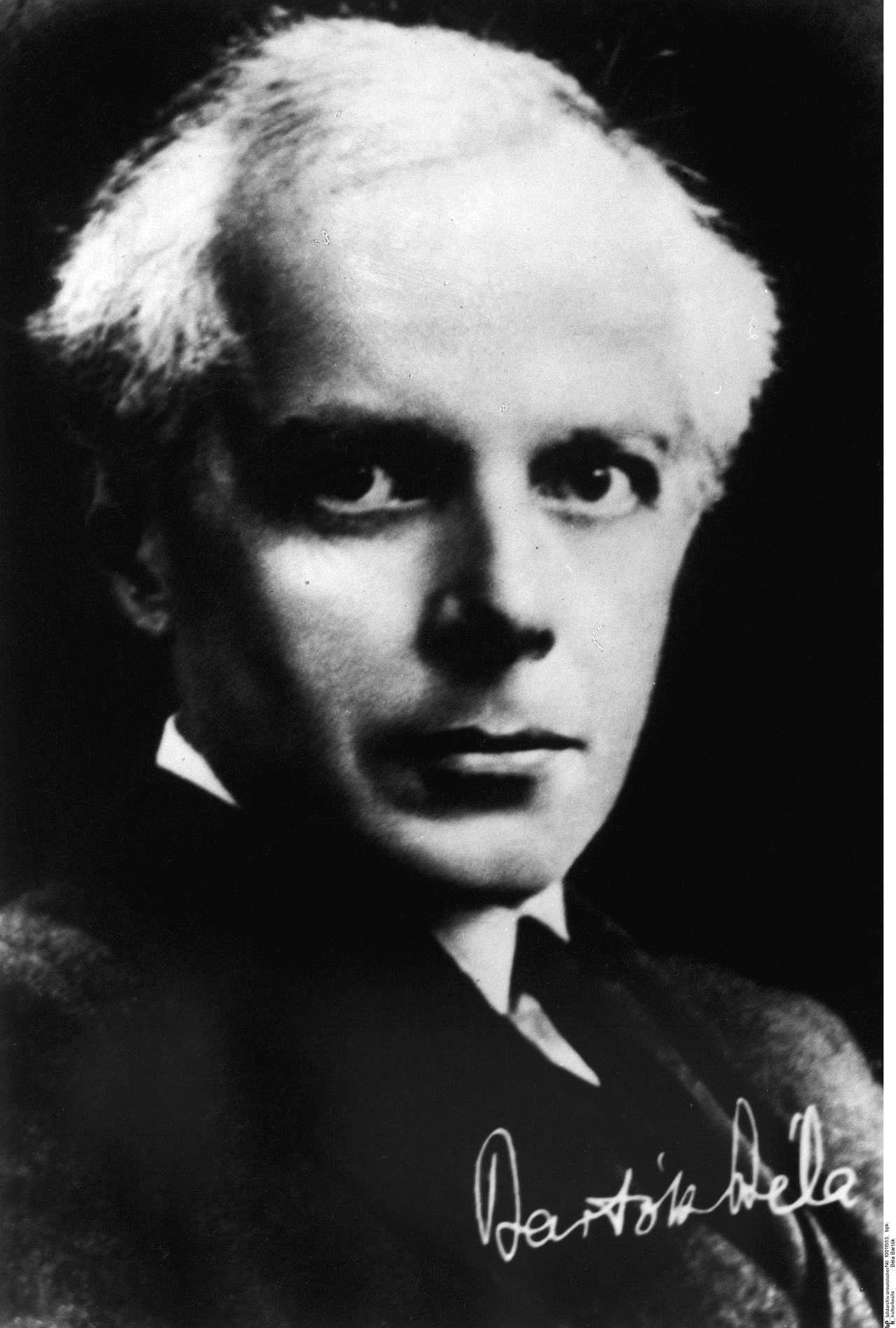

Béla Bartók

✒️1918–1924 | ⏰ 20 minutes

Béla Bartók

Born: 1881

Died: 1945

Béla Bartók wrote three works for the stage and all three centre on a male–female relationship, in particular a lonely male in search of love. The Duke in the opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle (1911) is repressed, abusive and carries a dark secret. In the ballet The Wooden Prince (1914–17) the Prince eventually attracts the attention of the Princess.

The final stage-work, the ballet The Miraculous Mandarin, returns to the darker nature of Duke Bluebeard’s Castle but, while the horrors there are psychological, here Bartók produced a score of raw immediacy – of violence, lust and a touch of the supernatural.

The scenario, by the Hungarian dramatist Menyhért Lengyel, concerns a girl forced into luring men into a shabby upstairs room, for them to be beaten and robbed by a gang of three pimps. The first victim is a dirty old man with no money: he is thrown out. The second is a young man, shy and more likeable, but equally penniless: he is also ejected. The Girl is under increasing pressure to pull in some cash, and her third customer is an imposing Mandarin.

From the start, his presence is ominous. At first he ignores the girl’s dancing, but he is soon seized by frenzied desire, and chases her around the room. The thugs take the Mandarin’s valuables and decide to finish him off. First they try to suffocate him but that fails; next they stab him but still he refuses to die. Then they hang him by his own pigtail but still he lives. It is only when the girl offers a genuine gesture of affection that the Mandarin finally expires.

The Miraculous Mandarin opens with a cacophonous prelude (Bartók’s intended ‘horrible pandemonium, din, racket and hooting’): a breathless thrill-ride depicting city bustle, with trombone and trumpet sounding a terrifying fanfare. Key pillars in the action are the three clarinet solos, which occur as the girl stands in the window to attract the next victim, and the graphic short tumbling figures as the thugs throw the first two men down the stairs. Sneering boozy trombones point to the first (old) man’s lewdness (and perhaps alcohol consumption), while a naive oboe solo reflects the younger man’s arrival.

The entrance of the Mandarin – terrifying trombones, joined by cymbal clashes – forms a climax. The girl’s dance for the Mandarin ends in a weird waltz, after which comes the frenzied chase. We are spared the three murder attempts, as this is where the action of the suite ends.

Given the debased subject matter, it’s no surprise that The Miraculous Mandarin was banned by the mayor of Cologne after its premiere, on 27 November 1926. One newspaper reported ‘catcalls, whistling, stamping and booing which went on for several minutes’. With its barbaric ostinatos (repeated rhythmic patterns), no doubt inspired by Stravinsky’s 1913 ballet The Rite of Spring, and its complex, other-worldly harmonies, in this work Bartók gave full expression to the scenario, which its writer aptly characterised as a ‘grotesque pantomime’.

Keep Listening

Delve deeper into the music featured in our Half Six Fix series, and find related music recommendations, with our Half Six Fix playlist.

The London Symphony Orchestra

At the London Symphony Orchestra we believe that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere – from orchestral fans in the concert hall to first-time listeners all over the world.

The LSO was established in 1904 as one of the first orchestras shaped by its musicians. Since then, generations of remarkable talents have built the Orchestra’s reputation for quality, daring, ambition and a commitment to sharing the joy of music with everyone. Today, the LSO is ranked among the world’s top orchestras, reaching well over 100,000 people in London, more on stages around the world, and millions through streaming, downloads, radio and television.

As Resident Orchestra at the Barbican since the Centre opened in 1982, we perform some 70 concerts there every year with our family of artists: Chief Conductor Sir Antonio Pappano, Conductor Emeritus Sir Simon Rattle, Principal Guest Conductors Gianandrea Noseda and François-Xavier Roth, Conductor Laureate Michael Tilson Thomas, and Associate Artists Barbara Hannigan and André J Thomas. The LSO has major artistic residencies in Paris, Tokyo and at the Aix-en-Provence Festival, and a growing presence across Australasia.

Through LSO Discovery, our learning and community programme, 60,000 people each year experience the transformative power of music, in person, on tour and online. Our musicians are at the heart of this unique programme, leading workshops, mentoring bright young talent, working with emerging composers, visiting children’s hospitals, performing at free concerts for the local community and using music to support neurodiverse adults. Concerts for schools and families introduce children to music and the instruments of the orchestra, with an ever-growing range of digital resources and training programmes supporting teachers in the classroom.

The ambition of LSO Discovery is to share inspiring, inclusive opportunities with performers, creators and listeners of all ages. The home of much of this work is LSO St Luke’s, our venue on

Old Street. In autumn 2025, following a programme of works, we will be re-opening the venue’s unique spaces to more people than ever before, with new state-of-the-art recording facilities and dedicated spaces for LSO Discovery’s programme.

Our record label LSO Live celebrates its 25th anniversary in 2024/25, and is a leader among orchestra-owned labels, bringing to life the excitement of a live performance. The catalogue of over 200 acclaimed recordings reflects the artistic priorities of the Orchestra – from popular new releases, such as Janáček’s Katya Kabanova with Sir Simon Rattle, to favourites like Vaughan Williams’ Symphonies with Sir Antonio Pappano and Verdi’s Requiem with Gianandrea Noseda.

Throughout its history, LSO Live has always been at the forefront of digital recording, sharing the LSO’s performances with millions of people around the world every month through streaming services, digital partnerships and an extensive programme of live-streamed and on-demand online broadcasts.

The LSO has been prolific in the studio since the infancy of orchestral recording, and has made more recordings than any other orchestra – over 2,500 projects to date – across film, video games and bespoke audio collaborations. Recent highlights include the Mercury-Music-Prize-nominated Promises collaboration with Floating Points and Pharoah Sanders, appearing on screen and on the soundtrack for the Oscar-nominated film Maestro, and an Emmy- and Grammy-nominated performance of Love Will Survive with Barbra Streisand.

Through inspiring music, learning programmes and digital innovations, our reach extends far beyond the concert hall. And thanks to the generous support of The City of London Corporation, Arts Council England, corporate supporters, trusts and foundations, and individual donors, the LSO is able to continue sharing extraordinary music with as many people as possible, across London, throughout the UK, and around the world.

Barbara Hannigan

LSO Associate Artist

Barbara Hannigan rarely seems to choose the easy path. Instead she is guided by how convinced she is by a piece of music, whether that’s the earliest opera or the latest contemporary work. ‘If I really believe in a piece,’ she says, ‘then I want others to hear it, and my whole career has been like that.’ Nearly 20 years ago she added another facet to her creative armoury – in addition to her dizzying range as a concert and opera singer, she also started to conduct: often, as tonight, performing both tasks simultaneously.

Now, as well as being an Associate Artist of the LSO, she is Principal Guest Conductor of both the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra and the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra. Next August she becomes Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Iceland Symphony Orchestra. Her eye (and ear) for innovative programming marries with a continual curiosity, an absolute immersion in the music and an understanding from the performer’s perspective, adding up to a unique artistic profile and performances of searing commitment.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Caroline Frenkel

Mitzi Gardner

Olatz Ruiz de Gordejuela

Julia Rumley

Second Violins

Harry Bennetts

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Alix Lagasse

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Csilla Pogány

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Helena Buckie

Violas

Santa Vižine

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Anna Bastow

Thomas Beer

Germán Clavijo

Steve Doman

Julia O’Riordan

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Mizuho Ueyama

Emily Clark*

Cellos

David Cohen

Laure Le Dantec

Salvador Bolón

Alastair Blayden

Daniel Gardner

Judith Fleet

Young In Na

Silvestrs Kalnins

Daniel Schultz*

Double Basses

Rodrigo Moro Martín

Patrick Laurence

Thomas Goodman

Chaemun Im

Joe Melvin

Gonzalo Jimenez

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Imogen Royce

Piccolo

Robert Looman

Oboes

Olivier Stankiewicz

Rosie Jenkins

Cor Anglais

Aurelién Laizé

Clarinets

Sérgio Pires

Chi-Yu Mo

Bass Clarinet

Ferran Garcerà Perelló

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Joost Bosdijk

Contrabassoon

Martin Field

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Amadea Dazeley-Gaist

Finlay Bain

Zachary Hayward

Trumpets

James Fountain

Adam Wright

James Nash

Trombones

Byron Fulcher

Jonathan Hollick

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Patrick King

Helen Edordu

Harps

Bryn Lewis

Helen Tunstall

Piano

Catherine Edwards

Celeste

Caroline Jaya-Ratnam

* LSO String Experience Scheme Member

Kindly supported by the Barbara Whatmore Charitable Trust, the Idlewild Trust and The Thriplow Charitable Trust.

Programme Notes Edward Bhesania. Edward Bhesania is a music journalist and editor who writes for The Stage, The Strad and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama.

LSO Visual Identity & Concept Design Bridge & Partners