Symphony No 1

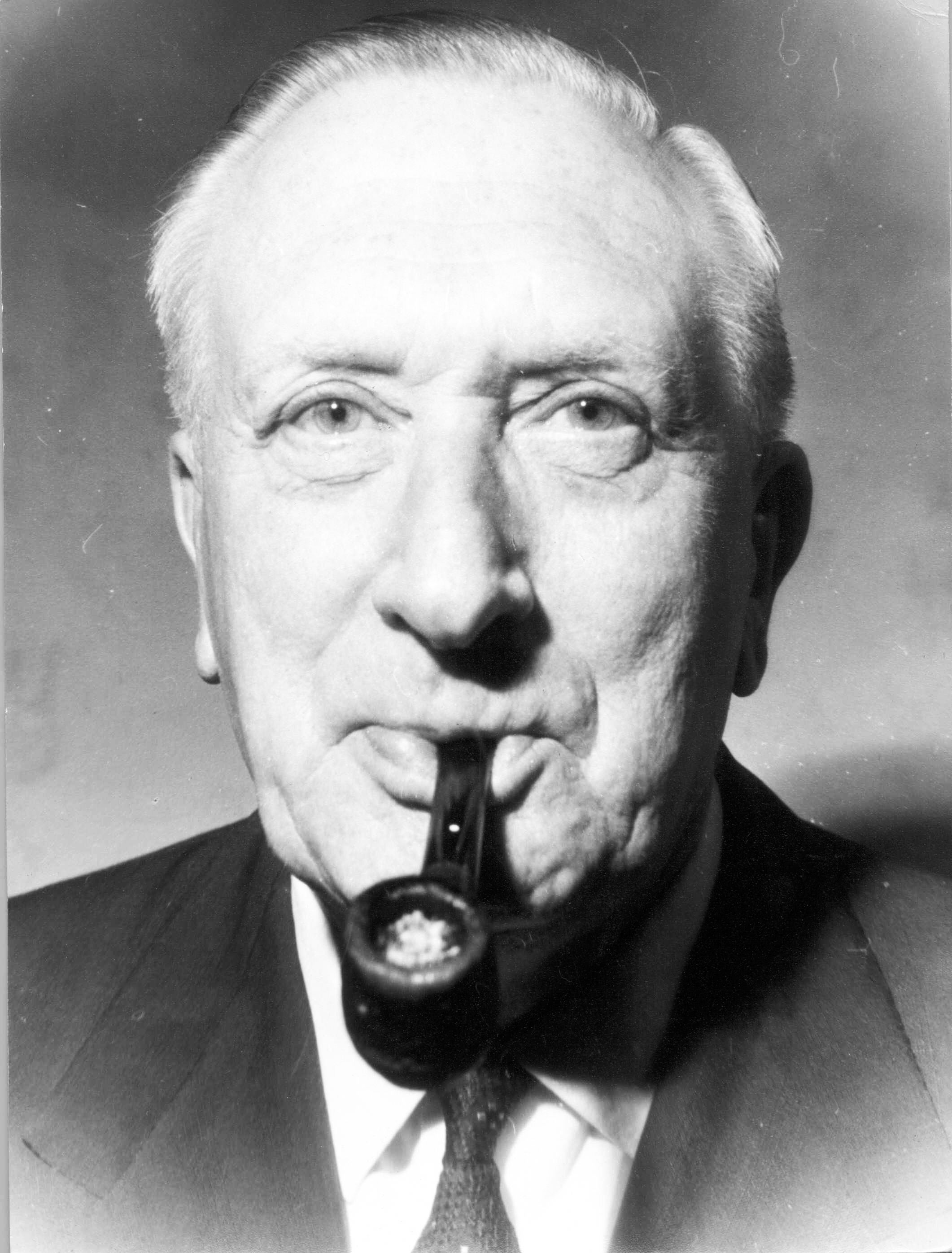

William Walton

✒️1932–35 | ⏰ 45 minutes

William Walton

Born: Oldham, England, 1902

Died: Ischia, Italy, 1983

‘I must make myself interesting somehow or when my voice breaks I’ll be sent back to Oldham.’

This, William Walton joked, was the reason he decided to become a composer – industrial Lancashire was not for him after experiencing the dreamy spires of Oxford as a chorister at Christ Church. He stayed on in Oxford as an undergraduate (though he failed his degree) and it was during this time that he met the well-to-do, artistic Sitwell siblings (Sacheverell, Osbert and Edith) – the first of a long line of acquaintances who supported his career. With Edith he produced the irreverent and controversial entertainment Façade, establishing him as an enfant terrible. Later successes included the Viola Concerto (1929), the colourful cantata Belshazzar’s Feast (1931) and the First Symphony (1932–5).

He contributed to state occasions (the marches Crown Imperial and Orb and Sceptre, for the coronations in 1937 and 1953 respectively, nod towards Elgar, a composer Walton admired) and was one of Britain’s earliest film composers (including the scores for Laurence Olivier’s Henry V, Hamlet and Richard III in the 1940s, as well as The Battle of Britain in 1969).

He met his young Argentine wife Susana in 1948; the following year the Waltons moved to the island of Ischia, off the coast of Naples, where he worked on the opera Troilus and Cressida. Further achievements include the Cello Concerto, Second Symphony and another opera, The Bear. His fusion of English choral and orchestral styles with the innovations of Stravinsky, Sibelius and others has assured his works a place in the forefront of 20th-century British music.

What's the story?

The premiere of William Walton’s Symphony No 1 in November 1935 was a turning point in British musical history. Although Edward Elgar had established himself back in 1908 (aged 51), as the bright new hope for the British symphony, Walton (in his early thirties) arrived on the scene as a disruptor, marrying an instinct for a killer tune with a distinctly 20th-century sound-world of fizzing rhythms, tart harmonies and colourful use of instruments. The response of conductor Henry Wood after hearing the performance was typical: ‘It was like the world coming to an end, its dramatic power was superb; what orchestration, what vitality and rhythmic invention – no orchestral work has ever carried me away so much.’

What makes this piece so special?

Walton had already begun a promising career by the time he was working on his First Symphony in 1932, although as a friend said, he was ‘desperately hard-up’. At first progress went well enough, possibly helped by a new, tempestuous, relationship with Baroness Imma Doernberg (a cousin of Princess Alice, herself a granddaughter of Queen Victoria). But then Doernberg left Walton for a Hungarian doctor. This abrupt end to their relationship may be what led him to add the direction con malizia (‘with malice’) to the second movement.

Walton struggled with the final (fourth) movement and meanwhile allowed the first three movements to be performed – by tonight’s orchestra, the LSO – in December 1934. It can’t have helped that he had agreed at the same time to write his first film score, Escape Me Never, an intense 10 days’ work for which he earned more than he made at the time in a year. By now he had met the ‘beautiful, intelligent’ Lady Alice Wimborne, who threw a lavish after-concert party at the Ritz Hotel. (‘I counted thirty-five guests and seventeen footmen,’ recalled one guest; ‘the most exquisite food … fantastically lovely crystal chandeliers … great splendour and beauty’.)

What is the music like?

The nervous, twitching figure in the second violins near the start sets the tone for much of the first movement. It’s a large canvas (around 15 minutes in length) but there is almost no let-up in forward movement – even in the more reflective episodes. The emotional temperature is high, with a number of climaxes suggesting inner turmoil and even white-hot despair.

The ‘con malizia’ movement is on the surface a jaunty scherzo (a light-hearted piece) but its pulse is unsettlingly off-kilter, and one motif in particular (first heard in the strings, marked ‘martellato’, or ‘hammered’) is unmistakably sneering. ‘Really sinister’ was the verdict of Walton’s friend and colleague Hubert Foss. After what seems like a clear conclusion, Walton tacked on a surprise, involuntary splutter – a measure of his wit and daring.

The slow third movement is the romantic heart of the symphony – for Walton, though something of a modernist, old-fashioned lyricism was not off limits. But this is not blissful tune-spinning; it is darkly impassioned, bittersweet. If this movement is any reflection of Walton’s feelings for Imma Doernberg, then it speaks of an attachment that was deeply personal, almost inescapable.

The finale is the movement Walton agonised over the longest. It carries his trademark ebullience – original yet distinctly English – as well as not one but two fugal episodes (in which a theme appears in close succession across different instrumental parts – a time-honoured display of a composer’s technique). At the same time there’s a grandeur and dazzle entirely in line with a composer who would go on to write around a dozen film scores.

Keep Listening

Delve deeper into the music featured in our Half Six Fix series, and find related music recommendations, with our Half Six Fix playlist.

Sir Antonio Pappano

Chief Conductor

After 22 years as Music Director of the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, Sir Antonio Pappano became Chief Conductor of the LSO. He was born just 20 miles away, in Epping, and moved to the US aged 13 but now lives in London. He has held lead positions with the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels (1992–2002) and the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome (2005–23). Opera is in his blood, and he brings this love of dramatic narrative and storytelling to his orchestral performances too. But he directs his players with great immediacy: his conducting style is unfiltered, impassioned and straight from the heart. A natural communicator about music, too, he has presented programmes for BBC TV. Last year he was appointed Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, having conducted at the Coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla last year.

The London Symphony Orchestra

At the London Symphony Orchestra, we strive to inspire hearts and minds through world-leading music-making. We were established in 1904 as one of the first orchestras shaped by its musicians, and today we’re ranked among the world’s top orchestras. As Resident Orchestra at the Barbican since the Centre opened in 1982, we perform some 70 concerts here every year. We also perform over 50 concerts a year to audiences throughout the UK and worldwide, and deliver a far-reaching programme of recordings, live-streams and on-demand broadcasts.

Through our world-leading learning and community programme, LSO Discovery, we’re connecting people from all walks of life to the power of great music. Our musicians are at the heart of this unique programme. In 1999 we formed our own recording label, LSO Live, which has become one of the world’s most talked-about classical labels. As a leading orchestra for film, we’ve entertained millions with classic scores for Star Wars, Indiana Jones and many more.

On Stage

Leader

Andrej Power

First Violins

Cellerina Park

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Maxine Kwok

Stefano Mengoli

Claire Parfitt

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Dániel Mészöly

Mabelle Park *

Hilary Jane Parker

Djumash Poulsen

Olatz Ruiz de Gordejuela

Rhys Watkins

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Thomas Norris

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Alix Lagasse

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Csilla Pogány

Louise Shackelton

Miya Väisänen

Ingrid Button

Mitzi Gardner

Polina Makhina

Shoshanah Sievers

Violas

Eivind Ringstad

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

Thomas Beer

Steve Doman

Sofia Silva Sousa

Mizuho Ueyama

Regina Beukes

Michelle Bruil

Errika Collins

Philip Hall

Martin Schaefer

Cellos

Rebecca Gilliver

Alastair Blayden

Salvador Bolón

Daniel Gardner

Amanda Truelove

Morwenna Del Mar

Silvestrs Kalnins

Jae Min Kang *

Ghislaine McMullin

Miwa Rosso

Peteris Sokolovskis

Double Basses

Rodrigo Moro Martín

Patrick Laurence

Thomas Goodman

Chaemun Im

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Matthew Gaffney *

Simon Oliver

Colin Paris

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Imogen Royce

Piccolo

Patricia Moynihan

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Olivier Stankiewicz

Layla Baratto

Cor Anglais

Sarah Harper

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bass Clarinet

Ferran Garcerà Perelló

Bassoons

Daniel Jemison

Joost Bosdijk

Horns

Diego Incertis Sánchez

Mihajlo Bulajic

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Jonathan Maloney

Trumpets

James Fountain

Thomas Fountain

Adam Wright

Katie Smith

Trombones

Helen Vollam

Merin Rhyd

Jonathan Hollick

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Patrick King

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

* LSO String Experience Scheme Member

Kindly supported by the Barbara Whatmore Charitable Trust, the Idlewild Trust and The Thriplow Charitable Trust.

Programme Notes Edward Bhesania. Edward Bhesania is a music journalist and editor who writes for The Stage, The Strad and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama.

LSO Visual Identity & Concept Design Bridge & Partners