Symphony No 4

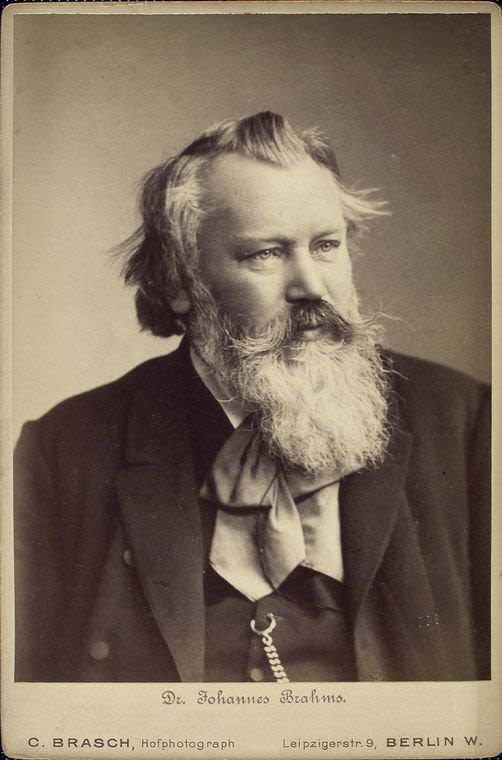

Johannes Brahms

✒️1884–5 | ⏰ 42 minutes

Johannes Brahms

Born: Hamburg, Germany, 1833

Died: Vienna, Austria, 1897

‘Without craftsmanship, inspiration is a mere reed shaken in the wind.’

One of the ‘three Bs’, after Bach and Beethoven, Johannes Brahms is often seen as a Classicist who happened to be born in the Romantic era. He worked mainly in the established forms – concerto, sonata, symphony – avoiding the more progressive tone-poems of Franz Liszt and the grandiose music-dramas of Richard Wagner.

From an early age he was forced to earn money for his family by playing the piano in Hamburg’s seedy sailors’ bars. Then, in 1853, a concert tour brought him famously into contact with Robert Schumann, who publicly declared the young composer a genius. After Schumann’s death in 1856, Brahms remained close to Schumann’s widow Clara. Their relationship, which lasted until her death in 1896, is documented in over 800 surviving letters.

From 1863 Brahms lived in Vienna. The German Requiem and Hungarian Dances swelled his reputation and his Variations on the St Anthony Chorale attracted attention ahead of his First Symphony. He wrote much choral music (he conducted both the Singakademie and the Singverein in Vienna) and led a pioneering revival of interest in Renaissance and Baroque music. He also composed over 200 songs and much chamber and piano music, but no opera. After his death in Vienna in 1897 he was buried next to Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert.

What's the story?

Brahms’ four symphonies came along a little like buses. He struggled for 18 years on the First, partly because the bar had been set high. The composer Robert Schumann had publicly named Brahms as the bright hope in Germany’s symphonic future.

On top of this, Brahms was painfully aware that he was following in the footsteps of Beethoven. ‘I shall never write a symphony!’ he wrote to his friend, the conductor Hermann Levi in 1870. ‘You have no idea what it’s like always to hear that giant marching along behind me’. But then, after he got the First out of his system, the next three symphonies followed relatively swiftly, within a decade.

Why is this piece so iconic?

Many people consider Brahms’ Fourth to be the greatest of his four symphonies, but it’s also his most tragic. At a playthrough on two pianos to some assembled friends, they were reportedly bemused. One of them, the critic Eduard Hanslick, said that ‘for the whole [of the first] movement I had the feeling I was being given a beating by two incredibly intelligent people’.

Another friend advised the composer to ditch the third movement and keep the final movement as a separate work. Brahms was clearly keen to manage expectations about what his symphony would be like. Writing to his friend the conductor Hans von Bülow from the Alpine resort town of Mürzzuschlag, where he worked on the Symphony in the summers of 1884 and 1885, he offered an insight into the tone of the symphony: ‘I’m really afraid it tastes like the climate around here. The cherries don’t ripen in these parts – you wouldn’t eat them!’

What is the music like?

The first movement opens with what seems like a free-wheeling lyrical theme, with babbling accompaniment, but on a closer listen the tune’s self-interruptions suggest uncertainty. Signalled by sudden fanfares, the second theme – for cellos – is more rousing. As the movement progresses, each idea carries through subtle markers from what came before it: what sounds like a seamless unfolding is actually underpinned by unswerving logic.

In contrast to the furrowed-brow ending of the first movement, the Andante moderato begins with a distant horn call that ushers in a gently circling tune on clarinet – a nocturnal serenade, intimately accompanied by plucked strings. A luminous romantic cello tune follows. ‘Every cellist … ’, said Brahms’ friend and confidante Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, ‘will revel in this glorious, long-drawn-out song breathing of summer.’ The tune becomes even richer when it returns in oozing strings before the end.

The third movement of a symphony is typically a scherzo – a light-hearted, jokey piece – and Brahms’ is marked ‘giocoso’ (playfully), though it defies convention by being in two beats to the bar rather than three, giving it an earthy march-like feel. Listen (and watch) out for the triangle – the only time Brahms used the instrument in his symphonies.

Unusually for a finale, Brahms chose the form of a passacaglia, in which variations are created around a repeating bass pattern (this one taken from Bach’s Cantata No 150). Here there are 30 variations, undergoing a variety of moods in a feat of ingenuity that proved Brahms was every bit a worthy sucessor to Beethoven.

Keep Listening

Delve deeper into the music featured in our Half Six Fix series, and find related music recommendations, with our Half Six Fix playlist.

Sir Simon Rattle

Conductor Emeritus

Sir Simon Rattle has an insatiable appetite for music. Whether it’s early or modern, classical or jazz, concert or opera, he brings a freshness of approach to everything he does. This year marks his 50th anniversary as a professional conductor. In the UK he has worked extensively in early music (with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment) and in opera (with the Glyndebourne Festival). For nearly two decades from 1980 he was at the helm of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he converted audiences to a richly varied musical diet. In 2002 he became the only Brit to become Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, and in 2017 he joined the LSO as Music Director, 40 years after he first conducted the Orchestra. Last year he became Chief Conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and the LSO’s Conductor Emeritus. This season he also took on the role of Principal Guest Conductor with the Czech Philharmonic.

The London Symphony Orchestra

At the London Symphony Orchestra, we strive to inspire hearts and minds through world-leading music-making. We were established in 1904 as one of the first orchestras shaped by its musicians, and today we’re ranked among the world’s top orchestras. As Resident Orchestra at the Barbican since the Centre opened in 1982, we perform some 70 concerts here every year. We also perform over 50 concerts a year to audiences throughout the UK and worldwide, and deliver a far-reaching programme of recordings, live-streams and on-demand broadcasts.

Through our world-leading learning and community programme, LSO Discovery, we’re connecting people from all walks of life to the power of great music. Our musicians are at the heart of this unique programme. In 1999 we formed our own recording label, LSO Live, which has become one of the world’s most talked-about classical labels. As a leading orchestra for film, we’ve entertained millions with classic scores for Star Wars, Indiana Jones and many more.

On Stage

Leader

Andrej Power

First Violins

Frederik Paulsson

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Stefano Mengoli

Claire Parfitt

Elizabeth Pigram

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Caroline Frenkel

Aleem Kandour

Dmitry Khakhamov

Kynan Walker *

Second Violins

Julián Gil Rodríguez

Sarah Quinn

Miya Väisänen

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Alix Lagasse

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Csilla Pogány

Helena Buckie

Mitzi Gardner

Dániel Mészöly

Violas

Eivind Ringstad

Gillianne Haddow

Anna Bastow

Thomas Beer

Steve Doman

Julia O’Riordan

Robert Turner

Emily Clark *

Fiona Dalgliesh

Jenny Lewisohn

Alistair Scahill

Elisabeth Varlow

Matthias Wiesner

Cellos

David Cohen

Laure Le Dantec

Alastair Blayden

Salvador Bolón

Ève-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Amanda Truelove

Young In Na

Ghislaine McMullin

Victoria Simonsen

Double Basses

Rodrigo Moro Martín

Patrick Laurence

Chaemun Im

Thomas Goodman

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Toby Hughes

Yuhan Ma *

Simon Oliver

Flutes

Joshua Batty

Imogen Royce

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Juliana Koch

Henrietta Cooke

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Bassoons

Rachel Gough

Joost Bosdijk

Contra Bassoon

Martin Field

Horns

Diego Incertis Sánchez

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Henry Ward

Jonathan Maloney

Trumpets

James Fountain

Jon Holland

Adam Wright

Trombones

Rebecca Smith

Jonathan Hollick

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Timpani

Patrick King

Percussion

Neil Percy

* LSO String Experience Scheme Member

Kindly supported by the Barbara Whatmore Charitable Trust, the Idlewild Trust and The Thriplow Charitable Trust.

Programme Notes Edward Bhesania. Edward Bhesania is a music journalist and editor who writes for The Stage, The Strad and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama.

LSO Visual Identity & Concept Design Bridge & Partners