Music born in silence:

Composers in self-isolation

If silence is the canvas upon which musicians work, few composers can have gone further to obtain it than John Luther Adams. In 1978, he moved to Alaska, and lived and composed for many years in a cabin facing the mountains: a place where, as he puts it, 'the keynote is silence'. But not every composer has the opportunity – or the inclination – to head for the wild. On the manuscript of his horn duos K487, Mozart scribbled the note 'Vienna, 27 July 1786, while playing skittles'. In other words, he seems to have written them while at the pub!

Still, most composers would probably admit that there are times when they need solitude, or at the very least, quiet. And many of them have found ingenious ways to self-isolate, to remove themselves temporarily from the noise and activity of domestic life. So come with us down the garden path into the secluded, very personal world of the composer’s hut…

Image: Mahler's composing hut in Lake Attersee, Austria

Gustav Mahler

1860–1911

Mahler never did anything by halves, and three of his huts survive, each built to his own specification. When he built a summer villa at Maiernigg in Carinthia in 1900, the hut was finished even before the house itself. Equipped with a baby grand piano, it was located in a forest clearing, high above lake Wörthersee, and Mahler composed here every summer from 1900 to 1907. His servants would lay breakfast for him before he started work each morning: bread, butter and marmalade plus coffee with hot milk, which he’d heat up himself over a spirit lamp. They had to return by a separate path: Mahler didn’t want to see a single human being while composing.

So his wife Alma knew that she was witnessing something special when, in the late summer of 1902, he played her the whole of his newly-completed Fifth Symphony, right there in the forest. 'It was the first time he had ever played a new work to me, and we walked, arm in arm up to his hut with all solemnity for the occasion', she recalled.

Mahler’s huts have become part of his personal legend. A fictional version featured in Ken Russell’s 1974 movie Mahler, floating on an Alpine lake (it’s actually Derwentwater) before exploding into flames to the strains of the Tenth Symphony.

Image: Grieg's composing hut in Troldhaugen, Norway

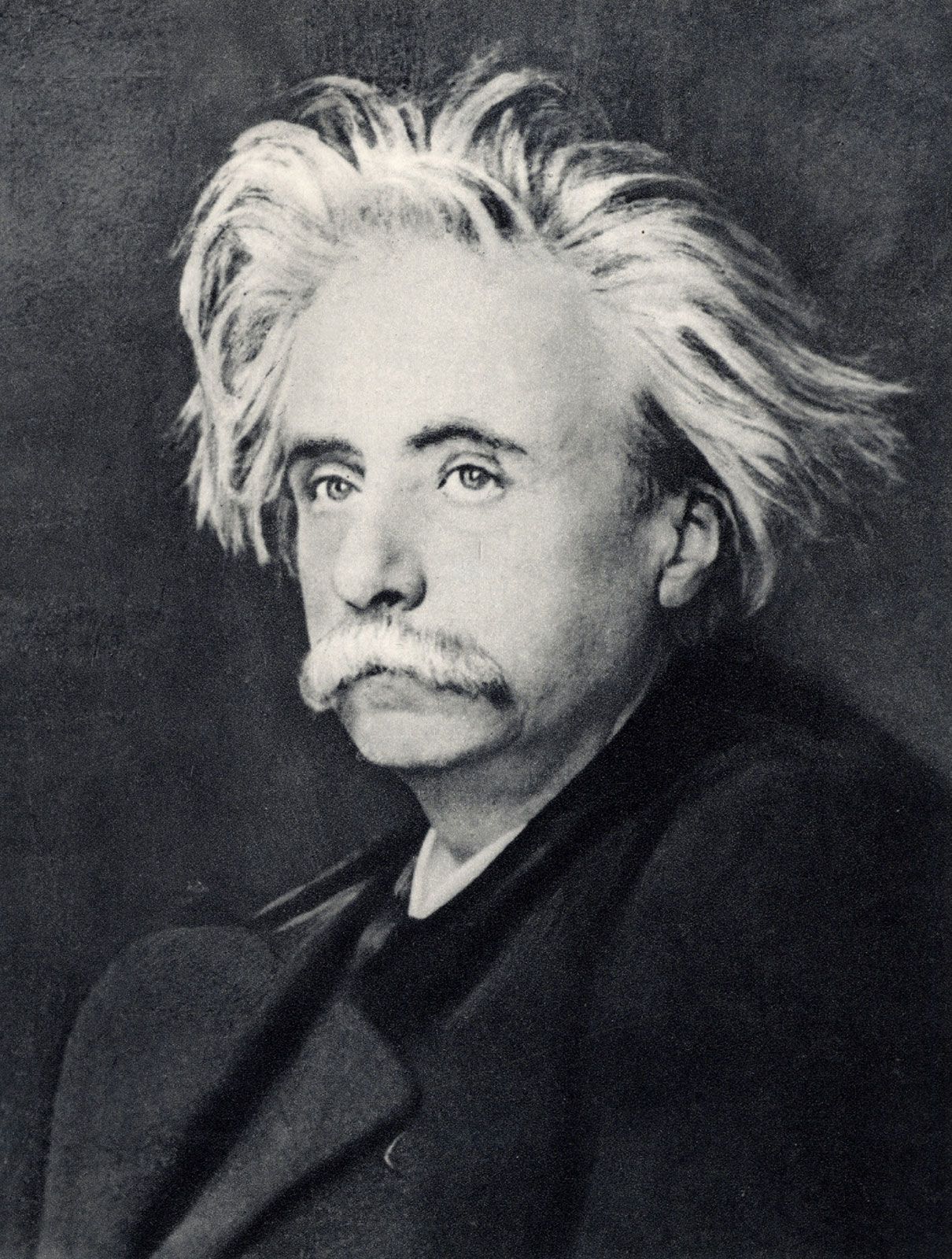

Edvard Grieg

1843–1907

Grieg’s composing hut is a jewel – down by the water’s edge at Troldhaugen, the rocky, birch-covered promontory near Bergen where he built his family home. Completed in 1891, it is painted a cheerful red against the surrounding leaves and water, and Grieg – who could be disturbed by the oars of a passing boat, let alone the constant stream of uninvited visitors to Norway’s greatest living composer – saw it as a refuge. An upright piano, a desk facing the fjord and of course a stove (vital in the Norwegian winter) were the main furnishings. At the end of each working day he would leave a handwritten note on his desk:

'If anyone should break in here, please leave the musical scores, since they have no value to anyone except Edvard Grieg.'

Ethel Smyth

1858–1944

Smyth grew up in Surrey, a daughter of the Raj; but the need for a music room of her own was a preoccupation throughout her youth. While studying in Leipzig in the 1870s, she was delighted to be able to rent a small attic, where she stored ham and butter in a birdcage on the window ledge (her landlady kept her well supplied with beer).

On settling back in England in 1894, Smyth bought a cottage called One Oak near Camberley, 'surrounded by fields and woods'. 'The last occupants of the two front rooms had been a pony and a donkey; the sanitary arrangements [were] practically non-existent', she wrote in her memoirs – and it proved difficult to hire servants for 'a small house where little ‘company’ was seen, and where the mistress played her own operas from morning to night'. Nonetheless, she managed to complete her operas Fantasio and Der Wald at One Oak, which survives, surrounded by suburbia, as a Toby Carvery.

Sometimes, composers need to isolate to get away from music, and this was certainly the case for British composer (and chemist!) Sir Edward Elgar…

Edward Elgar

1857–1934

The Ark, Elgar’s outhouse at Plas Gwyn (his home in Hereford from 1904 to 1911) actually served as a refuge from music. In the summer of 1908, needing a diversion from his First Symphony, he converted it into a chemical laboratory, producing his own soap and patenting a method for producing hydrogen sulphide. William Reed, leader of the LSO, tells how one afternoon Elgar concocted a particularly volatile compound of phosphorous. Dropping it into a water-butt for safety, he returned to the symphony when 'a sudden and unexpected crash, as of all the percussion in all the orchestras on earth, shook the room … the water-butt had blown up; the hoops were rent: the staves flew in all directions; and the liberated water went down the drive in a solid wall'. Pietro d’Alba – Elgar’s daughter’s pet rabbit, who lived in a nearby hutch – appears to have been unharmed!

Image: High Sierra mountain range, California

John Adams

b. 1947

In the 21st century, John Adams (the composer of Nixon in China: not to be confused with John Luther Adams) is probably classical music’s pre-eminent hut-dweller. As well as a purpose-built composing studio near his home on the Sonoma coast, north of San Francisco, he owns a mountain cabin in the High Sierra, where (according to his autobiography Hallelujah Junction) he has encountered 'spotted owls, mule deer, giant porcupines, and once, in a remote turn of a high mountain trail, a large mountain lion sitting in perfect stillness'.

His wilderness experiences informed his most recent opera, Girls of the Golden West, though isolation is not without its perils. In November 2017, Adams awoke to find his car doors wrenched open and its seats shredded by a passing bear. 'A bottle of beer in the trunk had popped open from the altitude, and he or she was apparently furious not to have been able to get to it', he told the New York Times, which puts Mahler’s servant worries into some sort of perspective.

Notes by Richard BratbyRichard Bratby writes on music and opera for The Spectator, Gramophone and The Arts Desk. He is the author of Forward: 100 Years of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

Always Playing

While we are unable to perform at the Barbican Centre and our other favourite venues around the world, we are determined to keep playing!

Join us online for a programme of full-length concerts twice a week, artist interviews, playlists to keep you motivated at home, activities to keep young music fans busy and much much more!

Visit lso.co.uk/alwaysplaying for the latest announcements.

In the meantime:

- Subscribe to our YouTube channel where you can watch over 500 videos.

- Follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter for great quizzes, listening suggestions and more.

- Sign up to our email list to be the first to hear about our new programme.