London Symphony Orchestra Spring 2021

Stravinsky

Welcome and Thank You for Watching

Whilst we are unable to come together with audiences at our Barbican home, we are pleased to continue releasing a programme of online content and streamed broadcasts, making music available for everyone to enjoy digitally. A warm welcome to the numerous conductors and soloists joining us, among them many firm friends and regular collaborators with the Orchestra.

It is a pleasure to invite you to watch and listen today online to this performance recorded in December 2020. I hope you enjoy the concert, and look forward to welcoming you back in person when we are able to re-open our doors.

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Kathryn McDowell CBE DL; Managing Director

Stravinsky

Octet for Wind Instruments

Symphonies of Wind Instruments

Orpheus

Four Norwegian Moods

Suite No 1

Suite No 2

Sir Simon Rattle conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

This performance is broadcast on YouTube. Available to watch for free for 90 days from Sunday 7 March 2021.

Recorded at LSO St Luke's on Tuesday 15 December 2020 in COVID-19 secure conditions.

Support the LSO's Future

The importance of music and the arts has never been more apparent than in recent months, as we’ve been inspired, comforted and entertained throughout this unprecedented period.

As we emerge from the most challenging period of a generation, please consider supporting the LSO's Always Playing Appeal to sustain the Orchestra, allow us to perform together again on stage and to continue sharing our music with the broadest range of people possible.

Every donation will help to support the LSO’s future.

You can also donate now via text.

Text LSOAPPEAL 5, LSOAPPEAL 10 or LSOAPPEAL 20 to 70085 to donate £5, £10 or £20.

Texts cost £5, £10 or £20 plus one standard rate message and you’ll be opting in to hear more about our work and fundraising via telephone and SMS. If you’d like to give but do not wish to receive marketing communications, text LSOAPPEALNOINFO 5, 10 or 20 to 70085. UK numbers only.

The London Symphony Orchestra is hugely grateful to all the Patrons and Friends, Corporate Partners, Trusts and Foundations, and other supporters who make its work possible.

The LSO’s return to work is supported by DnaNudge.

Generously supported by the Weston Culture Fund.

Share Your Thoughts

We always want you to have a great experience, however you watch the LSO. Please do take a few moments at the end to let us know what you thought of the streamed concert and digital programme. Just click 'Share Your Thoughts' in the navigation menu, or click here to go straight to the survey.

Igor Stravinsky

Octet for Wind Instruments

✒️1923 | ⏰16 minutes

1 Sinfonia: Lento – Allegro moderato

2 Tema con variazioni: Andantino

3 Finale: Tempo giusto

One group of eight players in a large space hardly seems surprising to us in these times of necessarily reduced ensembles playing where they can. Such circumstances were also often a needs-must of stricken post-World War I Europe. In the Paris Opera where a massive orchestra had taken part in the premiere of Stravinsky’s first large-scale masterpiece, The Firebird, in 1910, the number onstage on 18 October 1923 was actually nine: in addition to flute, clarinet and a pair each of bassoons, trumpets and trombones stood Stravinsky himself conducting the first performance of a work of his own. ‘The stage […] seemed a large frame,’ he later wrote, ‘but we were set off by a wall of screens, and the piece sounded well’.

The sonic combination was not unprecedented in Stravinsky’s music; he had also forged a new path in the Symphonies of Wind Instruments, premiered in a singular Russian requiem to Debussy, who had died four years earlier. Whether the inspiration for the Octet came to the composer in a dream, as he avowed in later life, or started, as he declared in his 1935 autobiography, ‘without [my] knowing what its sound medium would be’, the substance marks another staging post in his incredible gift for reinvention.

What Richard Taruskin has memorably called the ‘musical esperanto’ of Stravinsky’s post-Russian era has been labelled ‘neoclassical’ (though not by the composer himself, who ridiculed the term). In fact it is neo-everything. Bach (neo-Baroque, of course) is, perhaps inevitably, evoked by the contrapuntal elements, but while he looms large, Cubist-style, in the main sequences of the outer movements, a dizzyingly lopsided set of central variations on an unexpected theme include more populist marching, French or Russian ballet waltzes, Petrushka style, and a galop, while the finale gesture of the work is a nod in the direction of jazz.

Note by David Nice

Igor Stravinsky

Symphonies of Wind Instruments

✒️1920 | ⏰10 minutes

Stravinsky described his Symphonies of Wind Instruments as ‘an austere ritual which is unfolded in terms of short litanies between different groups of homogeneous instruments’. The starting point for its composition was the death of his friend, composer Claude Debussy in 1918. The closing chorale, arranged for piano, was published in December 1920, in a special edition of the magazine La Revue Musicale, called Tombeau de Claude Debussy. But by the time this appeared, Stravinsky had already completed the parent work, dedicated ‘to the memory of Claude Achille Debussy.’ It was first performed in London the following June under Serge Koussevitzky.

The work is scored for enlarged orchestral woodwind and brass sections. In its original form, the woodwind included alto flute and the rare alto clarinet. Stravinsky chose not to publish the score of this version during his lifetime. But in 1945, he made a radically revised version, among other things removing the alto flute and alto clarinet, and giving a much sharper edge to many of its attacks. This revision, published in 1947, became the standard version. But the original version remained available in sets of proof parts, and was preferred by several leading conductors. It eventually appeared in print in 2001.

The title of ‘Symphonies’ is used in its older sense of ‘sounding together’. The work is constructed in a series of short, intercut segments in different tempos and colours – a highly original procedure in 1920, which may have owed something to the then new art of film editing or ‘montage’, and which has had a profound influence on many later composers.

There are three related tempos, or speeds: Tempo II, half as fast as Tempo I; Tempo III, twice as fast. Tempo I has two different aspects: an incisive bell-like figure dominated by high clarinets; and slow-moving chord progressions for the full ensemble. Tempo II brings a series of winding, Russian-sounding melodies (reminiscent of Stravinsky’s 1913 The Rite of Spring) for small groups of woodwind, punctuated by more energetic outbursts. Tempo III does not appear until about halfway through the piece, and is used chiefly in two episodes – the first reminiscent of the orgiastic dances of The Rite of Spring, the second lighter on its feet.

Meanwhile the slow-moving version of Tempo I disappears from the mix, except in two short interjections of brass chords; but these prove to be anticipations of the memorial chorale, which emerges at full length to bring the work to a solemn end.

Note by Anthony Burton

Igor Stravinsky

Orpheus

✒️1947 | ⏰30 minutes

Scene 1

1 Lento sostenuto

2 Air de danse: Andante con moto

3 Dance of the Angel of Death: L’istesso tempo

4 Interlude: L’istesso tempo

Scene 2

1 Pas des Furies: Agitato in piano

2 Air de danse (Orpheus): Grave

3 Interlude: L’istesso tempo

4 Air de danse (concluded): L’istesso tempo

5 Pas d’action: Andantino leggiadro

6 Pas de deux: Andante sostenuto

7 Interlude: Moderato assai

8 Pas d’action: Vivace

Scene 3

1 Orpheus’ apotheosis: Lento sostenuto

Stravinsky’s penultimate ballet Orpheus was written towards the end of his so-called ‘neo-Classical’ period, which lasted from the 1920s to the early 1950s, after which he began to experiment with serial techniques. Orpheus was begun in the autumn of 1946 in response to a commission from Lincoln Kirstein, founder of the Ballet Society (later the New York City Ballet), and the choreographer George Balanchine who, like Stravinsky, had emigrated to the US from his native Georgia. Balanchine had already collaborated with Stravinsky on two previous ballets, Apollon musagète and Jeu de cartes, and conducted the New York premiere on 28 April 1948. Nearly a decade later, Agon completed a triptych of ballets on ancient Classical subjects.

Orpheus deals with the myth that inspired operas by Claudio Monteverdi and Christoph Gluck, but covers the protagonist’s violent death and his apotheosis. It is divided into three scenes, beginning after the death of Euridice. The first sees the inconsolable Orpheus mourning his lover, a harp representing his lyre, over a chorale-like theme played by strings. Orpheus’ friends (represented by woodwind) arrive to offer condolences, and the Angel of Death, represented by a solo violin, appears (Air de danse). The Angel takes Orpheus to Hades to seek his dead wife; during an atmospheric Interlude, they appear in the gloom of the Underworld, their arrival heralded by trumpet calls.

Scene Two introduces the Furies, who dance agitatedly, while making veiled threats towards the intruder. Stravinsky himself said that ‘the music for the Furies is soft, and constantly remains on the soft level, like most of the rest of this ballet’. Then comes a slow ‘Air de danse’, as Orpheus employs his lyre to move the gods of the Underworld to pity. As he dances, the tormented souls in Hades stretch out their arms to him, imploring him to continue his heart-melting song (Interlude: L’istesso tempo). He continues his ‘Air de danse’, and Hades calms down. The Furies surround Orpheus, bind his eyes, and return Euridice to him (Pas d’action: Andante sostenuto). The newly reunited pair dance a Pas de deux, but Orpheus can no longer bear not to see his wife. He tears the bandage from his eyes, and Euridice falls dead once more (plucked strings). In a third Interlude, Orpheus returns to Earth, and in a violent and dramatic ‘Pas d’action’, he meets his end at the hands of the Bacchantes, who tear him to pieces.

A dignified calm returns in ‘Orpheus’ apotheosis’. In the ancient legend, his severed head continued its song, and now the harp resumes its first theme, accompanied by a subdued dirge for two horns, solo violin and muted trumpet. In Stravinsky’s words, ‘Apollo enters. He wrests the lyre from Orpheus and raises his song heavenwards'.

Note by Wendy Thompson

Igor Stravinsky

Four Norwegian Moods

✒️1942 | ⏰8 minutes

1 Intrada

2 Song

3 Wedding Dance

4 Cortege

As composer-artisan, Stravinsky could, and did, turn his hand to a whole range of unusual commissions, and several of those cropped up after his move to the United States in 1940 – not least the Circus Polka for Barnum and Bailey’s elephants and a ballet for a Broadway revue. Hollywood, where he and his beloved second wife Vera settled, certainly beckoned.

As it turned out, none of his scores found any place in the projected movies; music for the vision scene in The Song of Bernadette ended up at the heart of his work Symphony in Three Movements (1942–45), while a hunting scene for Jane Eyre became the ‘Eclogue’ of his 1943 Ode. The music Stravinsky did write for Columbia Pictures’ The Commandos Strike at Dawn, about Britain’s part in Norway’s resistance to the Nazis, became the Four Norwegian Moods (or ‘Modes,’ as Stravinsky later implied in declaring imperfect English for the title).

These beautifully crafted miniatures are among the few works Stravinsky did not feature in his own vast discography as conductor. He seems not to have included any actual war music in his score, for they are simply Norwegian dances; the third actually begins as if it intends to be another of those by Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg. There are deft games of instrumental pairs, the horns leading the way, some clarinet writing that could only be Stravinsky, familiar metrical tricks and a very beautiful cor anglais solo against strings in No 2. The fourth dance, like moments of the first, comes closest to another of Stravinsky's works, the delectable Danses Concertantes, also from the early 1940s.

Note by David Nice

Igor Stravinsky

Suites Nos 1 & 2

✒️1921 & 1925 | ⏰5 minutes & 6 minutes

Suite No 1

1 Andante

2 Napolitana

3 Espanola

4 Balalaika

Suite No 2

1 March

2 Waltz

3 Polka

4 Galop

Such easy pieces yet such complicated histories among these cosmopolitan miniatures, produced between Stravinsky's three early ballets for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes (The Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite of Spring) and the completion of his next Russian trilogy (The Soldier’s Tale, Renard, Les noces).

Most representative of the complicated genesis of the two Suites is the ‘Polka’ of Suite No 2. It was one of three piano-duet pieces dashed off in 1916 for Diaghilev to play with another of the Ballets Russes’ leading lights, Walter Nouvel. Dedicating it to the impresario, Stravinsky remarks in his 1935 autobiography how ‘I told him that in composing it I had thought of him as circus ring master in evening dress and top hat, cracking his whip and urging on a rider’. Diaghilev, incidentally, only needed one hand for the simple bass lines. In 1921 Stravinsky arranged it for a cabaret band as a number in a sketch at the Russian-émigré club in Paris, La Chauve-Souris (The Bat), for the star, Zhenya Nikitina, to dance to. He seems to have had an affair with this lady, but it was another glamorous woman at the cabaret, Vera, wife of Sergei Sudeikina, who would become the second Mrs Stravinsky.

By 1921, as well as Les Cinqs Doigts for solo piano, Stravinsky had composed five more pieces for two pianists at one piano: this time for himself using two hands on the left, and two of his children alternating above. So whereas the first three had a simple left hand and a more difficult right, it was the other way around. His travels with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, somewhat surprising in the thick of World War I, had taken him to Italy – hence the tarantella whirl of the ‘Napoletana’ – and to Spain – the ‘Espanola’, where the piano version is more authentic in its evocation of flamenco guitar.

Curiously ‘Balalaika’ sounds more like the Parisian musiquette of composer Francis Poulenc and company, which was shortly to emerge, than any Russian strumming. Elsewhere, there are shades of Petrushka, both in the parody waltz and the bitonal character arising from two to four chords in the left hand, something more elaborate in the right, throughout the first three pieces to be composed, though the ingenuity is less obvious in the scoring for smallish orchestra. If anything, it reminds us that fellow Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich was to take up his cue in the incidental music he provided for Soviet cabaret in the 1920s, while the penchant for only the white notes of the piano, evident in ‘Andante’, was something that was increasingly favoured by another Russian composer, Sergei Prokofiev.

Note by David Nice

Igor Stravinsky

17 June 1882 (Russia) – 6 April 1971 (United States)

The son of the Principal Bass at the Mariinsky Theatre, Igor Stravinsky was born at the Baltic resort of Oranienbaum near St Petersburg in 1882. Through his father he met many of the leading musicians of the day and came into contact with the world of musical theatre. In 1903 he became a pupil of composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, which allowed him to get his orchestral works performed and as a result he came to the attention of Sergei Diaghilev, who commissioned a new ballet from him, The Firebird.

The success of The Firebird, and then Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913), confirmed his status as a leading young composer. Stravinsky now spent most of his time in Switzerland and France, but continued to compose for Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes: Pulcinella (1920), Mavra (1922), Renard (1922), Les Noces (1923), Oedipus Rex (1927) and Apollo (1928).

Stravinsky settled in France in 1920, eventually becoming a French citizen in 1934, and during this period moved away from his Russianism towards a new ‘neo-classical’ style. Personal tragedy in the form of his daughter, wife and mother all dying within eight months of each other, and the onset of World War II, persuaded Stravinsky to move to America in 1939, where he lived until his death. From the 1950s, his compositional style again changed, this time in favour of a form of serialism. He continued to take on an exhausting schedule of conducting engagements until 1967, and died in New York in 1971. He was buried in Venice on the island of San Michele, close to the grave of Diaghilev.

Composer profile by Andrew Stewart

Artist Biographies

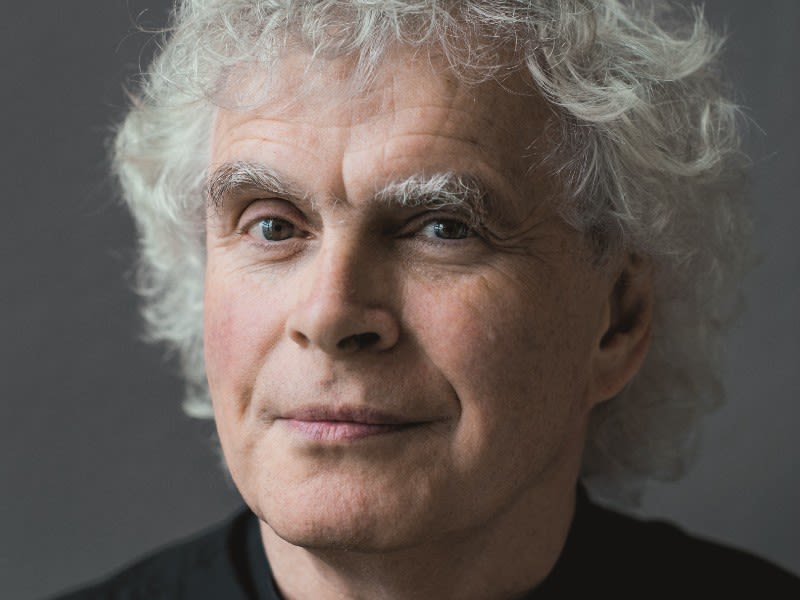

Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Music Director

Sir Simon Rattle was born in Liverpool and studied at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1980 to 1998, he was Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Music Director in 1990. He moved to Berlin in 2002 and held the positions of Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic until he stepped down in 2018. Sir Simon became Music Director of the London Symphony Orchestra in September 2017 and spent the 2017/18 season at the helm of both ensembles.

Sir Simon has made over 70 recordings for EMI record label (now Warner Classics) and has received numerous prestigious international awards for his recordings on various labels. Releases on EMI include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (which received the 2009 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance) Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Ravel’s L'enfant et les sortileges, Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite, Mahler’s Symphony No 2 and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. From 2014 Sir Simon continued to build his recording portfolio with the Berlin Philharmonic’s new in-house label, Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings, which led to recordings of the Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius symphony cycles. Sir Simon’s most recent recordings include Rachmaninoff's Symphony No 2, Beethoven's Christ on the Mount of Olives and Ravel, Dutilleux and Delage on Blu-Ray and DVD with LSO Live.

Music education is of supreme importance to Sir Simon, and his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic broke new ground with the education programme Zukunft@Bphil, earning him the Comenius Prize, the Schiller Special Prize from the city of Mannheim, the Golden Camera and the Urania Medal. He and the Berlin Philharmonic were also appointed International UNICEF Ambassadors in 2004 – the first time this honour has been conferred on an artistic ensemble. Sir Simon has also been awarded several prestigious personal honours which include a knighthood in 1994, becoming a member of the Order of Merit from Her Majesty the Queen in 2014 and most recently, was bestowed the Order of Merit in Berlin in 2018. In 2019, Sir Simon was given the Freedom of the City of London.

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904, and is built on the belief that extraordinary music should be available to everyone, everywhere.

Through inspiring music, educational programmes and technological innovations, the LSO’s reach extends far beyond the concert hall.

Visit our website to find out more.

On Stage

Leader

Roman Simovic

First Violins

Carmine Lauri

Clare Duckworth

Ginette Decuyper

Laura Dixon

Gerald Gregory

Maxine Kwok

William Melvin

Claire Parfitt

Laurent Quénelle

Harriet Rayfield

Sylvain Vasseur

Second Violins

Julian Gil Rodriguez

Thomas Norris

Sarah Quinn

David Ballesteros

Matthew Gardner

Naoko Keatley

Csilla Pogany

Belinda McFarlane

Iwona Muszynska

Andrew Pollock

Paul Robson

Violas

Edward Vanderspar

Gillianne Haddow

Malcolm Johnston

German Clavijo

Stephen Doman

Carol Ella

Sofia Silva Sousa

Robert Turner

Cellos

Noel Bradshaw

Rebecca Gilliver

Alastair Blayden

Eve-Marie Caravassilis

Daniel Gardner

Laure Le Dantec

Double Basses

Colin Paris

Patrick Laurence

Matthew Gibson

Joe Melvin

Jani Pensola

Flutes

Gareth Davies

Patricia Moynihan

Imogen Royce

Piccolo

Sharon Williams

Oboes

Olivier Stankiewicz

Rosie Jenkins

Cor Anglais

Sarah Harper

Clarinets

Chris Richards

Chi-Yu Mo

Basset Horn

Katy Ayling

Bassoons

Daniel Jemison

Shelly Organ

Contra Bassoon

Dominic Morgan

Horns

Timothy Jones

Angela Barnes

Alexander Edmundson

Jonathan Maloney

Trumpets

David Elton

Niall Keatley

Robin Totterdell

Trombones

Matthew Knight

Mark Templeton

Bass Trombone

Paul Milner

Tuba

Ben Thomson

Timpani

Nigel Thomas

Percussion

Neil Percy

David Jackson

Sam Walton

Harp

Bryn Lewis

Piano

Elizabeth Burley

Meet the Members of the LSO on our website

Thank You for Watching