Sunday 10 May

Romeo and Juliet

Berlioz Romeo and Juliet

Valery Gergiev conductor

Olga Borodina mezzo-soprano

Kenneth Tarver tenor

Evgeny Nikitin bass-baritone

London Symphony Chorus

Guildhall School Chorus

Simon Halsey chorus director

Concert recorded in November 2013

Hector Berlioz

Romeo & Juliet

1839

Dramatic symphony after Shakespeare's tragedy.

Libretto by Émile Deschamps

PART I

Introduction: Fighting – Tumult – Intervention of the Prince

Prologue – Strophes – Scherzetto

PART II

Romeo alone: Distant music and dancing; The Capulets' feast

Love Scene: The Capulets' garden, silent and deserted; Capulets leaving the banquet

The Queen Mab Scherzo

PART III

Juliet's Funeral Procession

Romeo at the Capulets' Tomb: Invocation: Juliet awakens; Delirious joy – Death of the two lovers

Finale: The crowd rushes to the cemetery – Brawl; Friar Lawrence's recitative, aria and oath of reconciliation

Almost from the moment that the 23-year-old Berlioz saw an English company’s performance of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet at the Odéon Theatre in Paris in September 1827, ideas for some kind of musical response began to crowd into his mind. But the article in an English newspaper, which later reported that as he left the theatre he exclaimed, ‘I shall write my grandest symphony on the play’, could not have been more wrong.

Writing a symphony of any kind was the last thing Berlioz would have been thinking of at that stage of his career. His musical education, since coming to Paris from the provinces six years before – a boy of 17 who had never heard an orchestra – had been largely devoted to the operas and sacred music of the French classical school. The crucial discovery of Beethoven, and of the symphony as a major art-form, lay several months ahead.

THE REVELATION OF BEETHOVEN

Berlioz’s Romeo and Juliet comes out of Beethoven almost as much as Shakespeare – out of the revelation of the Beethovenian symphony at concerts at the Paris Conservatoire, where Berlioz was a student, in 1828: the symphony as a dramatic medium every bit as vivid and lofty as opera, and the symphony orchestra as a vehicle of unimagined expressive power and subtlety, of infinite possibility. From that time on, his aspirations turned in a new direction, towards the dramatic concert work, culminating, twelve years after the epiphany at the Odéon, in Romeo and Juliet.

For Berlioz, listening to the Beethoven symphonies and studying the scores in the Conservatoire Library, the sheer variety of their compositional procedures and the clearly distinct character of each work reinforced the lessons of Shakespeare: continual reinvention of form in response to the demands of the poetic material. Each of his three symphonies is cast in a different form, and adopts a different solution to the problem of communicating dramatic content: in the Symphonie fantastique a written programme, in Harold in Italy movement titles, in Romeo and Juliet choral recitative, setting out – as in Shakespeare’s ‘Two houses, both alike in dignity …’ – the action distilled in the movements that follow.

The project occupied Berlioz for a long time. In Italy, in 1831–32, he discussed with Mendelssohn a possible orchestral scherzo on Queen Mab (a fairy that Mercutio refers to in a famous speech), and – under the (to him) negative impact of Bellini’s 1830 opera The Capulets and the Montagues – imagines an ideal scenario for a dramatic work:

‘To begin, the dazzling ball at the Capulets, where amid a whirling cloud of beauties young Montague first sets eyes on ‘sweet Juliet’ whose constant love will cost her her life; then the furious battles in the streets of Verona, the ‘fiery Tybalt’ presiding like the very spirit of rage and revenge; the indescribable night scene on Juliet’s balcony, the lovers’ voices ‘like softest music to attending ears’ uttering a love as pure and radiant as the smiling moon that shines its benediction upon them; the dazzling Mercutio and his sharp-tongued, fantastical humour; the naïve old cackling nurse; the stately hermit, striving in vain to calm the storm of love and hate whose tumult has carried even to his lowly cell; and then the catastrophe, extremes of ecstasy and despair contending for mastery, passion’s sighs turned to choking death; and, at the last, the solemn oath sworn by the warring houses, too late, on the bodies of their star-crossed children, to abjure the hatred through which so much blood, so many tears, were shed.’

Much of this will feature in the symphony that Paganini’s princely gift – a cheque for 20,000 francs, which relieved Berlioz of the heavy burden of debt – enabled him to write.

BERLIOZ ON LSO LIVE

Gramophone Magazine’s Editor's Choice

BBC Music Magazine’s BBC Music Choice

BBC Radio 3 CD Review’s First Choice Recording

Classic FM Magazine’s Best Buy

THE FORMAL PLAN

The work finally performed in the Conservatoire Hall in November 1839 was the result of long and careful consideration of ends and means. ‘Romeo and Juliet, Dramatic Symphony, with chorus, vocal solos, and prologue in chanted recitative, after Shakespeare’s tragedy, dedicated to Niccolò Paganini’, is its title. Berlioz’s later preface has an ironic edge:

‘There will doubtless be no mistake as to the genre of this work.’

In fact there has been a great deal. Yet (as the preface continues):

‘Although voices are frequently employed, it is neither a concert opera nor a cantata but a choral symphony.’

Nowadays, Mahler’s multi-movement vocal-orchestral constructions are accepted as symphonies, but they were long disputed. In Berlioz’s Romeo and Juliet, the balance between the symphonic and the narrative is exactly calculated (with the wordless love scene at the heart of the work, structurally and emotionally). The more one studies it, the stronger its compositional grasp appears. So far from being arbitrary – an awkward compromise between symphony and opera or oratorio – the scheme is logical and the mixture of genres (the joint legacy of Shakespeare and Beethoven) precisely gauged.

The fugal Introduction, depicting the feud of the two families, establishes the principle of dramatically explicit orchestral music and then, using the bridge of instrumental recitative (as in Beethoven’s Ninth), crosses over into vocal music. Choral Prologue now states the argument – which Choral Finale will resolve – and prepares for the themes, dramatic and musical, to be treated in the core of the symphony by the orchestra. In addition, the two least overtly dramatic movements, the adagio (Love Scene) and the scherzo, are prefigured, the one in a contralto solo celebrating the rapture of first love, the other in a scherzetto for tenor and semi-chorus which introduces the mischievous Mab. At the end, the Finale brings the drama fully into the open in an extended choral movement that culminates in the abjuring of the hatreds depicted orchestrally at the outset.

THE USE OF VOICES

Throughout, voices are used enough to keep them before the listener’s attention, in preparation for their full deployment. In the Love Scene, the songs of revellers on their way home from the ball float across the stillness of the Capulets’ garden. Two movements later, in the Funeral Procession, the Capulet chorus is heard. The use of chorus thus follows what Berlioz (in an essay on the Ninth Symphony) called ‘the law of crescendo’.

It also works emotionally: having begun as onlookers, the voices become participants, just as the anonymous contralto and the Mercutio-like tenor give way to an actual person, the saintly Friar Laurence. At the same time the two movements preceding the Finale take on an increasingly descriptive character, the funeral dirge merging into an insistent bell-like tolling and the Tomb Scene taking the work still nearer to narrative. In this way the fully dramatic Finale evolves out of what has gone before.

No Berlioz score is more abundant in lyric poetry, in a sense of the magic and brevity of love, in ‘sounds and sweet airs’ of so many kinds …

LISTENING GUIDE

Thematic resemblances and echoes constantly link the different sections. The Introduction’s trombone recitative, representing the Prince’s rebuke to the warring families, is formed from the notes of their angry fugato, stretched out and ‘mastered’; the ball music is transformed to give the departing guests their dreamlike song; in the Tomb Scene Juliet wakes (clarinet) to the identical notes of the rising cor anglais phrase in the opening section of the adagio, and this is followed by the great love theme, now blurred and torn apart as the dying Romeo relives it in distorted flashback. And in the Finale, as the families’ vendetta breaks out again over the bodies of their children, the return of the opening fugato unites the two extremes of the vast score. The principle is active to the end: Friar Laurence’s oath of reconciliation takes as its point of departure the Introduction’s B minor feud motif, reborn in a broad, magnanimous B major.

Within his outward form the music is motivically close-knit. At the same time no Berlioz score is more abundant in lyric poetry, in a sense of the magic and brevity of love, in ‘sounds and sweet airs’ of so many kinds: the flickering, fleet-footed scherzo, which stands not only for Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech but for the whole nimble-witted, comic-fantastical, fatally irrational element in the play, and in which strings and wind seem caught up in some gleeful yet menacing game; the noble swell of the great extended melody which grows out of the questioning phrases of ‘Roméo seul’; the awesome unison of cor anglais, horn and four bassoons in Romeo’s invocation in the Capulets’ tomb; the haunting beauty of Juliet’s funeral procession (an addition to the play by David Garrick, whose edited version of Romeo and Juliet Berlioz saw at the Odéon Theatre); the adagio’s deep-toned harmonies and spellbound melodic arcs, conjuring the moonlit night and the wonder and intensity of the passion that flowers beneath it.

Note by David CairnsDavid Cairns won the biography category of the Whitbread Prize and the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction for his second volume biography on Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness. Working alongside Sir Colin Davis since the 1950s, their Berlioz reputation goes before them: ‘Cairns and Davis made Berlioz not just acceptable, but almost normal, a patient, rational craftsman, a great composer like any other’ (Mark Swed, Los Angeles Times).

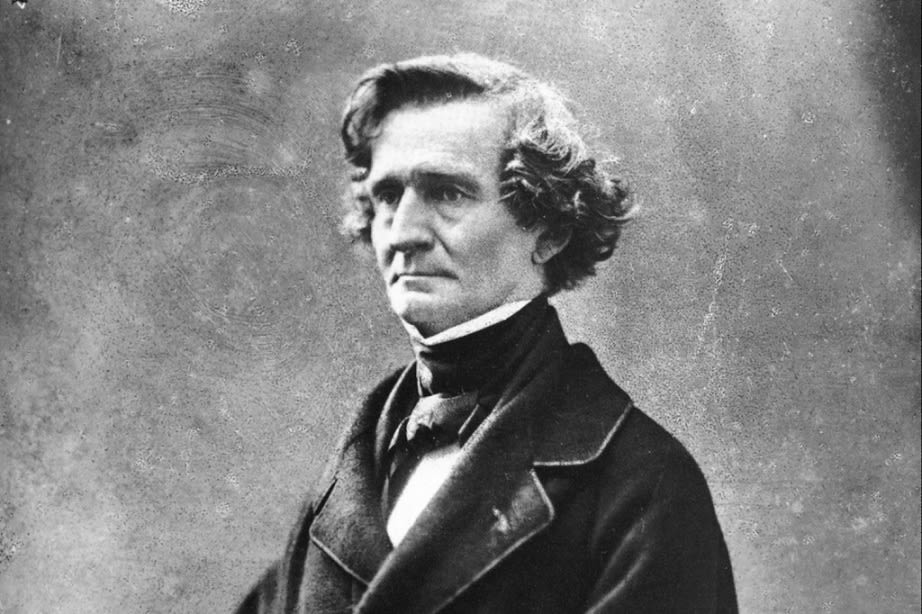

Hector Berlioz

1803–69

Hector Berlioz was born in south-east France in 1803, the son of a doctor. At the age of 17 he was sent to Paris to study medicine, but had already conceived the ambition to be a musician and soon became a pupil of the composer Jean-François Le Sueur.

Within two years he had composed the Messe solennelle, successfully performed in 1825. In 1826 he entered the Paris Conservatoire, winning the Prix de Rome four years later. Gluck and Spontini were important influences on the formation of his musical style, but it was his discovery of Beethoven at the Conservatoire concerts, inaugurated in 1828, that was the decisive event in his apprenticeship, turning his art in a new direction: the dramatic concert work, incarnating a ‘poetic idea’ that is ‘everywhere present’, but subservient to musical logic.

His first large-scale orchestral work, the autobiographical Symphonie fantastique, followed in 1830. After a year in Italy he returned to Paris and began what he later called his ‘Thirty Years War against the routineers, the professors and the deaf’. The 1830s and early 1840s saw a series of major works, including Harold in Italy (1834), Benvenuto Cellini (1836), the Grande Messe des Morts (1837), the Shakespearean dramatic symphony Romeo and Juliet (1839), the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale (1840) and Les nuits d’été (c 1841). Some were well-received; but he soon discovered that he could not rely on his music to earn him a living. He became a prolific and influential critic – a heavy burden for a composer but one that he could not throw off.

In the 1840s he took his music abroad and established a reputation as one of the leading composers and conductors of the day. He was celebrated in Germany (where Liszt championed him), in Russia (where receipts from his concerts paid off the debt from the Parisian failure of The Damnation of Faust), in Vienna, Prague, Budapest and London. These years of travel produced less music. In 1849 he composed the Te Deum, which had to wait six years to be performed. But the unexpected success of L’enfance du Christ in Paris in 1854 encouraged him to embark on a project long resisted: the composition of an epic opera on The Aeneid, which would assuage a lifelong passion and pay homage to two great idols, Virgil and Shakespeare.

Although Béatrice et Bénédict (1860–62) came later, the opera The Trojans (1856–58) was the culmination of his career. It was also the cause of his final disillusionment and the reason, together with the onset of ill-health, why he wrote nothing of consequence in the remaining six years of his life. The work was cut in two, and only part performed in 1863, in a theatre too small and poorly equipped. Berlioz died in 1869.

Profile by David Cairns

MORE BERLIOZ IN MAY

Sunday 31 May 2020, 7pm BST

Berlioz The Damnation of Faust

conducted by Sir Simon Rattle

Valery Gergiev

conductor

Valery Gergiev is a vivid representative of the St Petersburg conducting school. His debut at the Mariinsky (then Kirov) Theatre came in 1978 with Prokofiev's War and Peace. In 1988, Valery Gergiev was appointed Music Director of the Mariinsky Theatre, and in 1996, he became its Artistic and General Director.

With his arrival at the helm, it became a tradition to hold major festivals, marking various anniversaries of composers. The Mariinsky Orchestra under Valery Gergiev has scaled new heights, assimilating not just opera and ballet scores, but also an expansive symphony music repertoire.

Under Gergiev's direction the Mariinsky Theatre has become a major theatre and concert complex. The Concert Hall was opened in 2006, followed in 2013 by the theatre's second stage (the Mariinsky-II), while since January 2016, the Mariinsky Theatre has had a branch in Vladivostok – the Primorsky Stage. 2009 saw the launch of the Mariinsky label, which to date has released more than 30 discs that have received great acclaim from critics and the public throughout the world.

Valery Gergiev successfully collaborates with the world's great opera houses and has led world renowned orchestras, such as World Orchestra for Peace (which he has directed since 1997), the Philharmonic Orchestras of Berlin, Paris, Vienna, New York and Los Angeles, the Symphony Orchestras of Chicago, Cleveland, Boston and San Francisco, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (Amsterdam) and many other ensembles. From 1995 to 2008, Valery Gergiev was Principal Conductor of the Rotterdam Philharmonic (of which he remains an honorary conductor to this day), and from 2007 to 2015 of the London Symphony Orchestra. Since autumn 2015, the maestro has headed the Munich Philharmonic.

Valery Gergiev is the founder and director of prestigious international festivals including the Stars of the White Nights (since 1993) and the Moscow Easter Festival (since 2002), among many others. Since 2011, he has directed the organisational committee of the International Tchaikovsky Competition. Valery Gergiev's musical and public activities have brought him acclaimed awards such as the Hero of Labour (2013), the Order of Alexander Nevsky (2016), the Russian Federation Ministry of Defence Arts and Culture Award (2017) and prestigious State awards of Armenia, Bulgaria, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, France and Japan.

Olga Borodina

mezzo-soprano

Grammy-award winning mezzo-soprano Olga Borodina is a star of the Kirov Opera, regularly appearing with the major opera houses and orchestras around the world. Winner of the Rosa Ponselle and Barcelona Competitions, she made her highly acclaimed European debut at the Royal Opera House in 1992, sharing the stage with Plácido Domingo in Samson and Delilah – performances that launched her international solo career.

Olga Borodina has since returned to Covent Garden on many occasions, and also performs frequently at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, making her debut in Boris Godunov in 1997. She has made many concert appearances with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra under James Levine at Carnegie Hall, and has performed with the world’s greatest orchestras and conductors. In recital, she has performed in venues in London (Wigmore Hall, Barbican), Milan (La Scala), Vienna (Konzerthaus), San Francisco (Davies Symphony Hall), Rome (Accademia di Santa Cecilia), Hamburg (Staatsoper), Paris (Théatre des Champs Elysées) and Amsterdam (Concertgebouw), among others. Recent highlights have included Amneris in Verdi's Aida at both the Vienna State Opera and the Metropolitan Opera, and a televised gala from Avery Fisher Hall in New York.

Olga Borodina’s releases on Philips Classics include a number of operas, solo recital recordings and, recently, the double album A Portrait of Olga Borodina featuring a collection of songs and arias. Her recent Verdi Requiem recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Riccardo Muti won two Grammys in 2011.

Olga Borodina was awarded People’s Artist of Russia in 2002, and in 2007 was the recipient of the State Prize, the highest accolade in Russia.

Kenneth Tarver

tenor

Kenneth Tarver is considered to be one of the outstanding belcanto tenors of his generation, acknowledged for his beauty of tone, virtuosic technique, extensive and even vocal range, coupled with an attractive and elegant stage presence. A specialist in Mozart and demanding virtuosic operatic repertoire, he has appeared at the most prestigious opera houses and concert halls around the world, performing both well-known and seldom-performed works with conductors such as René Jacobs, Riccardo Chailly, Pierre Boulez, and Claudio Abbado.

Kenneth Tarver has amassed an impressive repertoire of both well-known and seldom performed masterpieces with conductors such as Alberto Zedda (Rossini’s Moïse et Pharaon, L’Inganno Felice, La Gazza Ladra, La Scala di Seta, Adelaide di Borgogna) Riccardo Chailly (Stravinsky’s Pulcinella, both Bach’s St Matthew and St John Passion), Carlo Rizzi (Rossini’s Armida), Bobby McFerrin: (Handel’s Messiah) or Frans Brüggen: (Mozart’s Requiem). Other highlights include Rodion Shchedrin’s My Age, My Wild Beast at the Verbier Festival, a film of Judith Weir’s Armida for Channel 4, Orff’s Carmina Burana at the Musikverein Vienna and Mozart’s Requiem at the Tanglewood Festival conducted by James Levine.

Kenneth Tarver is a past winner of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and was a member of the Metropolitan Opera’s Young Artist Development Programme and the Staatsoper Stuttgart. A graduate of Interlochen Arts Academy, The Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, Kenneth holds a Masters of Music Performance from Yale University School of Music, where he received the Dean’s Award for the Most Outstanding Student in the graduating class.

Evgeny Nikitin

bass-baritone

Nikitin hails from Murmansk, in the very north of Russia. His first love was to compose, sing and play drums and guitar in heavy metal bands, but his vocal gift took him in a different direction. He was accepted at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1992 and was soon combining his studies with his first solo engagements at the famed Mariinsky Theatre under Valery Gergiev’s direction. It wasn’t long before he was invited to major theatres and festivals throughout Europe, the Americas and Asia.

Image: Marco Borggreve

Image: Marco Borggreve

Concert performances include Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death at the Schleswig Holstein Festival and at the Berlin Philharmonic, the Coronation and Death of Boris Godunov with the Accademia di Santa Cecilia Rome, Mahler’s Symphony No 8and Rubinstein’s The Demon with the LSO, Oedipus Rex with the Müncher Philharmoniker and Verdi’s Requiem with the National Symphony Orchestra Washington.

He sings regularly at the Mariinsky theatre and at the Stars of the White Nights Festival, performing his favourite roles: the eponymous Boris Godunov, Filippo (Verdi's Don Carlo), Holländer (Wagner's The Flying Dutchman), Amfortas (Wagner's Parsifal), Wotan (Wagner's Das Rheingold), The Wanderer (Wagner's Siegfried), and Don Giovanni (Mozart).

Simon Halsey

chorus director

Simon Halsey occupies a singular position in classical music. He is the trusted advisor on choral singing to the world’s greatest conductors, orchestras and choruses, and also an inspirational teacher and ambassador for choral singing to amateurs of every age, ability and background. By making singing a central part of the world-class institutions with which he is associated, he has been instrumental in changing the level of symphonic singing across Europe.

Image: Matthias Heyde

Image: Matthias Heyde

He holds positions across the UK and Europe as Choral Director of the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus; Chorus Director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Chorus; Artistic Director of Orfeó Català Choirs and Artistic Adviser of the Palau de la Música; Barcelona; Artistic Director of the Berlin Philharmonic Youth Choral Programme; Creative Director for Choral Music and Projects of WDR Rundfunkchor; Director of the BBC Proms Youth Choir; Artistic Advisor of the Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival Choir; Conductor Laureate of the Rundfunkchor Berlin; and Professor and Director of Choral Activities at the University of Birmingham. He is also a highly respected teacher and academic, nurturing the next generation of choral conductors on his post-graduate course in Birmingham and through masterclasses at Princeton, Yale and elsewhere.

Halsey has worked on nearly 80 recording projects, many of which have won major awards, including a Gramophone Award, Diapason d’Or, Echo Klassik, and three Grammy Awards with the Rundfunkchor Berlin. He was made Commander of the British Empire in 2015, was awarded The Queen’s Medal for Music in 2014, and received the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 2011 in recognition of his outstanding contribution to choral music in Germany.

London Symphony Chorus

The London Symphony Chorus was formed in 1966 to complement the work of the London Symphony Orchestra and is renowned internationally for its concerts and recordings with the Orchestra. Their partnership was strengthened in 2012 with the appointment of Simon Halsey as joint Chorus Director of the LSC and Choral Director for the LSO, and the Chorus now plays a major role in furthering the vision of LSO Sing, which also encompasses the LSO Community Choir, LSO Discovery Choirs for young people and Singing Days at LSO St Luke’s.

The LSC has worked with many leading international conductors and other major orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain and the European Union Youth Orchestra. It has also toured extensively in Europe and has visited the US, Israel, Australia and south-east Asia.

The partnership between the LSC and LSO, particularly under Richard Hickox in the 1980s and 1990s, and later with the late Sir Colin Davis, led to its large catalogue of recordings, which have won numerous awards.

The Chorus is an independent charity run by its members. It is committed to excellence, to the development of its members, to diversity and engaging in the musical life of London, to commissioning and performing new works, and to supporting the musicians of tomorrow. For more information, please visit lsc.org.uk.

The LSO was established in 1904 and has a unique ethos. As a musical collective, it is built on artistic ownership and partnership. With an inimitable signature sound, the LSO’s mission is to bring the greatest music to the greatest number of people.

The LSO has been the only Resident Orchestra at the Barbican Centre in the City of London since it opened in 1982, giving 70 symphonic concerts there every year. The Orchestra works with a family of artists that includes some of the world’s greatest conductors – Sir Simon Rattle as Music Director, Principal Guest Conductors Gianandrea Noseda and François-Xavier Roth, and Michael Tilson Thomas as Conductor Laureate.

Through LSO Discovery, it is a pioneer of music education, offering musical experiences to 60,000 people every year at its music education centre LSO St Luke’s on Old Street, across East London and further afield.

The LSO strives to embrace new digital technologies in order to broaden its reach, and with the formation of its own record label LSO Live in 1999 it pioneered a revolution in recording live orchestral music. With a discography spanning many genres and including some of the most iconic recordings ever made the LSO is now the most recorded and listened to orchestra in the world, regularly reaching over 3,500,000 people worldwide each month on Spotify and beyond. The Orchestra continues to innovate through partnerships with market-leading tech companies, as well as initiatives such as LSO Play. The LSO is a highly successful creative enterprise, with 80% of all funding self-generated.

Image: Ranald Mackechnie

Thank you for watching.

You can enjoy this concert and more on the Stingray Classica app.

By watching this broadcast you are supporting the LSO. Click to find out about other ways to support the LSO, or to make a donation.

Always Playing

While we are unable to perform at the Barbican Centre and our other favourite venues around the world, we are determined to keep playing!

Join us online for a programme of full-length concerts twice a week plus much more, including ‘Coffee Sessions’ with LSO musicians, playlists, recommendations and quizzes.

Stay updated:

- Follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter

- Sign up to our email list to be the first to hear about our new programme

- Subscribe to our YouTube channel

Join us for our next full-length concert

Thursday 14 May 2020, 7.30pm BST

Mendelssohn Symphony No 3

Mendelssohn Overture: The Hebrides, ‘Fingal’s Cave’

Schumann Piano Concerto

Mendelssohn Symphony No 3, ‘Scottish’

Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor

Maria João Pires piano